There are several basic approaches to achieving a 3D scan, but one you may not have heard of is photometric stereo scanning.

3D scanning is an increasingly popular technology that’s gained a hold in several application niches, including:

- Quality control for manufactured parts

- Capturing a representation of historical objects or buildings

- Portrait-style 3D captures of people

- Collecting virtual versions of scenes and objects for VR / AR applications

Most of the existing products providing 3D scanning functionality use one of a few base techniques:

- Photogrammetry, where a (large) series of images taken from different angles are processed by software into a 3D model

- Structured Light, where a known light pattern is passed over a varying surface, and optical sensors observe how the pattern’s appearance changes to determine 3D structure

- Laser Scanning, where a laser illuminates points on an object that are combined to create a point cloud

- Infrared Ranging, where an array of infrared beams reflect off a surface and return time indicates the physical distance to each point.

- LIDAR, where a beam of light determines the distance to points on an object

You can find 3D scanning products in each of these categories, and they are each best used in particular scenarios. Some products are quite expensive, while others are almost free.

There’s one more 3D scanning technique I recently encountered that doesn’t seem to have a commercial hold yet: photometric stereo scanning.

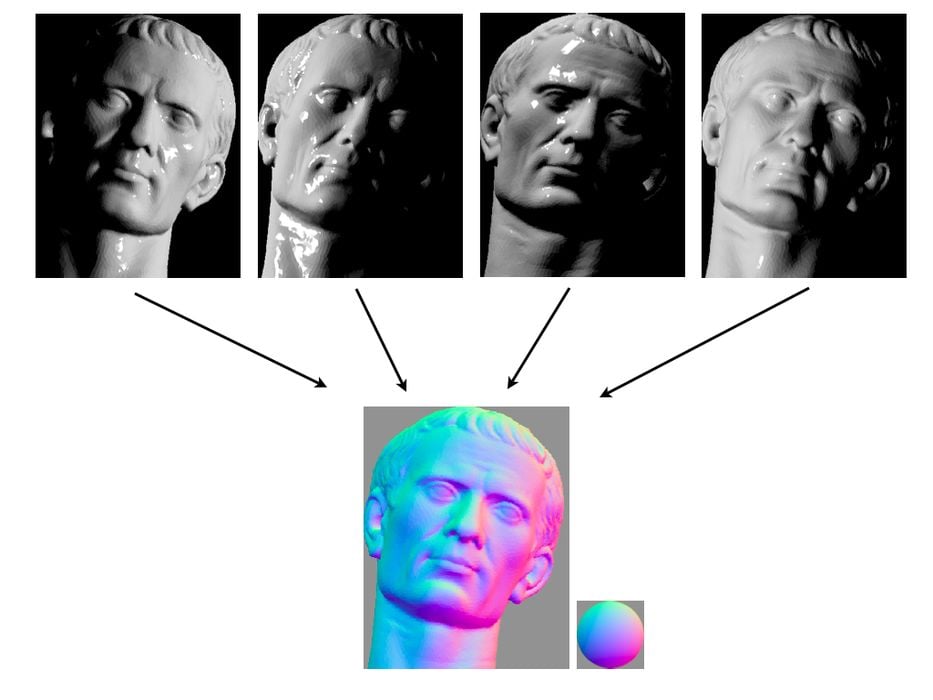

The photometric stereo process involves imaging an object under different lighting conditions.

The idea is to project light at an object from a variety of different angles. At each angle there are different shadows generated from the surface contours. By analyzing the changing nature of these shadows it is actually possible to determine the 3D shape of an object.

This intuitively makes sense, but photometric stereo does not seem to be a technology available in popular 3D scanning products.

This is likely because there are constraints on how photometric stereo can perform. My impression is that there is still research underway for this technology. One researcher working on photometric stereo posted this (long) video explaining how it works:

As you can see if you went through the video, this technology is not quite ready for commercial use. But there is potential.

Should it become commercialized, we may see relatively inexpensive 3D scanning setups available: the hardware would consist of a camera, direct lighting and possibly a turntable. The magic happens in the software.

Should someone perfect the software and open source it, then this could happen sooner than later.

Via Wikipedia