In the near future, there may be complications for companies as increasing numbers of home-built spare parts are produced.

In the wild days of the consumer 3D printing craze in 2012-14, many believed everyone would soon own a 3D printer. These devices would be used to produce all manner of items at home, including 3D figurines, toys, and, of course, spare parts for appliances.

That vision never happened, not only because of the inaccessibility of suitable 3D models, but also because the machines of the day were relatively rudimentary and broke more often than they worked. Many a machine from those days sits idle today, having suffered a mere filament jam with no one knowing how to fix it.

Consumer interest in home 3D printing quickly waned, and manufacturers rapidly shifted towards professional and industrial markets, leaving consumer 3D printing to the smaller realm of DIY folks.

And that was the end of mass consumer 3D printing, or so I thought.

But times may be changing. In recent years there has been a slow evolution of equipment and software, softening the long-standing barriers to technology use among consumers.

Today’s equipment is far more capable, reliable and safe. A “3D printer kit” is no longer a pile of wires, nuts and bolts, but is typically a slightly disassembled unit that can be put together by anyone in a few moments.

For 3D models, there have never been as many available — often for free — from online repositories. As of this writing, Thingiverse, the original kingpin of printable 3D models, has almost five million 3D models in its vast data store.

On the software side, tools like Tinkercad open up the possibility of creating one’s own 3D designs. That tool and similar efforts are easily learnable by almost anyone.

Even more advanced CAD tools, in particular Autodesk’s Fusion 360, are increasingly accessible through free-access programs and online training. With such tools it’s possible for many people to create their own spare parts.

I believe this is happening now. As the 3D printer manufacturers in aggregate continue to pour out many tens of thousands of devices each month, they are all going somewhere. Somebody is using these machines.

And an increasing proportion of them have the capability of making their own spare parts.

What could this mean?

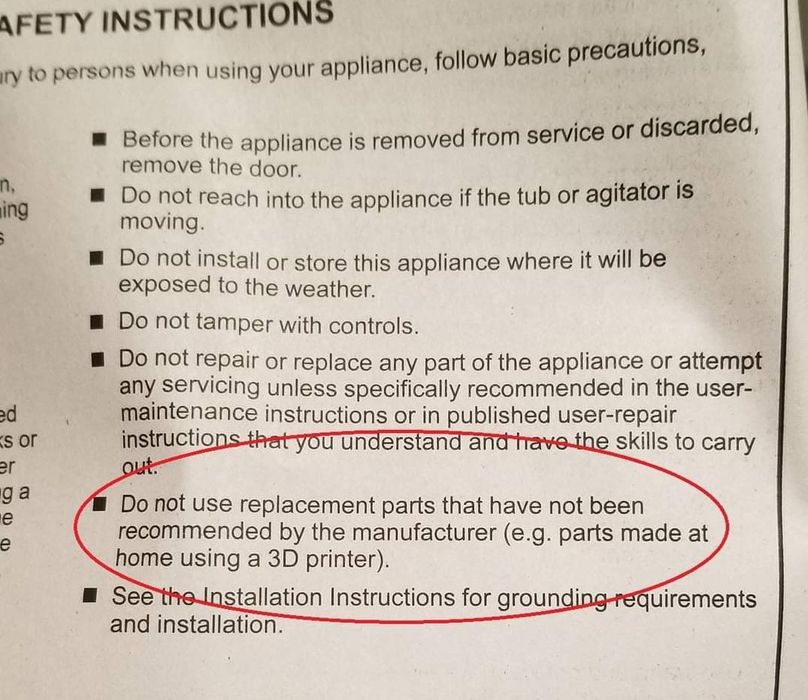

One clue is given by the image at top, apparently taken from a recent Maytag washing machine manual. Why would a company put such a statement in their operating manual?

I think it’s because of two reasons.

First, appliance companies make a tremendous amount of money on spare parts. That dishwasher knob that broke will have to be replaced with the official version at a cost of US$39, while production of it would certainly be less than US$1.

Secondly, there is a liability factor. Companies spend considerable effort obtaining safety certifications for their equipment, and ensure they maintain them by producing exactly the same products each time. All materials should be the same, all designs should be the same, etc.

That’s broken when a user replaces a part with a home-built equivalent, which might not be equivalent in regulatory terms. I suspect companies might fear legal action should something go wrong with a product as a result of home-built part use.

But how could a manufacturer truly stop this from happening? With a million 3D printers in homes and the ability to design — and share — spare part designs independently of the manufacturer, we could see many examples of this happening.

I suspect we will soon see similar warnings appear on other products, and eventually there could be legislation involved. It’s possible manufacturing lobbyists could push for laws preventing such activity, but that would be against the current trend of the “right to repair”.

One way or another, it’s likely we’ll see an increasing number of personally produced spare parts as capabilities increase.

I know this is happening — because I’m doing it myself.