UK-based Wayland Additive has released some additional details of their unusual NeuBeam metal 3D printing process.

The company first announced NeuBeam last year, when they described it as a variation of the EBM (electron beam melting) process used by several companies, including Arcam. The claim to fame is that they somehow found a way to neutralize electromagnetic effects that can spoil EBM prints. This opened the door for them to use many more material types with NeuBeam.

The company was set to announce further details and display equipment this month, but apparently decided to delay things until May for reasons that likely include the pandemic.

However, with that delay they felt they should tell us something, which is in fact exactly what they did.

The new information deals with their in-process monitoring (IPM) system.

IPM is often done by metal 3D printers, as the parts produced on such equipment are typically production / end-use items. They must be of suitable quality or they will be rejected by buyers. This has led to a significant interest in ensuring quality for most metal 3D printing systems, and Wayland Additive is no different.

Most of the IPM systems will monitor basic items such as temperature of the meltpool as the laser traverses the powder bed in LPBF systems, as well as keeping track of the build chamber temperatures. However, Wayland Additive’s IPM system seems a lot more comprehensive.

It turns out they are using not one IPM system, but three independent systems on their Calibur3 metal 3D printers.

A high-resolution CMOS imaging camera is able to view the build chamber in IR wavelengths to monitor heat. The camera runs at 100 FPS, making it possible to see heat in real time at all points. It is also possible to configure this sensor to examine smaller areas of the build plane at much higher resolutions, and this allows for capture rates of up to an incredible 25,000 FPS.

The second IPM sensor is a structured light scanner. This is a technique typically used for tabletop or handheld 3D scanners to capture 3D models. In this case it repeatedly 3D scans the powder bed for anomalies.

For example, if the recoater blade did not properly lay down a layer of powder, it would immediately be detected and action could be taken to resolve the issue. Similarly, if a part warped slightly and caused the powder surface to distort, this could also be detected.

Finally, the third sensor is a backscattered electron detector. This very unusual sensor is applicable to EBM systems and allows Wayland Additive to “see” how the phasing occurs in the meltpool, as well as observing localized ionization.

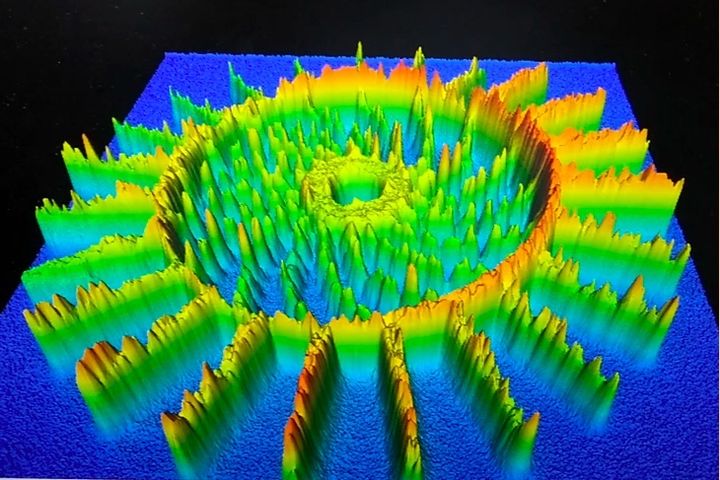

The information collected from these sensors can be constructed into 3D views that show great detail on a given 3D print job. For example, a 3D heat map of a part could be displayed.

Another possibility is to link the three sensor data sets into a unified view of the entire job process, which could reveal all kinds of interesting aspects.

Wayland Additive says at this point the sophisticated IPM system is currently usable for post-print analysis and defect detection. However, they also say eventually they will integrate its knowledge into the system in real time, allowing for a closed-loop quality management approach.

From the description of this IPM system, it would appear that Wayland Additive’s Calibur3 system should produce high-quality metal 3D prints.

Via Wayland Additive