A unique application for 3D printing has been developed by a student at Texas A&M.

The application is intended for the oil and gas industry, where the use of “fracking” has revolutionized drilling techniques in recent decades.

Fracking involves introducing fractures into an underground region, in hopes that oil can flow through the fractures and be recovered. But how do those fractures remain clear and able to carry efficient volumes of material?

This is done through an injection of what’s called “proppants”. This is essentially a sand mixture, where the particles are of differing sizes. The ideas is that these small rocks will enter the fractures, but not block them. Their strength will keep the fractures from naturally closing. The proppants are different sizes so that fractures of all sizes can be accommodated.

Texas A&M explains:

“Oil recovery in shale reservoirs usually begins with hydraulic fracturing, where fluid is forced into the rock formation at high pressures to fracture or crack the shale. Proppants, different sized grains of sand, are flushed down in a fluid slurry to hold these fractures open after the high pressure is released so oil and gas can flow to the well. Diverters, which are chemical or mechanical materials that can later be dissolved or recovered, are sometimes injected to strategically block main slurry paths so proppants are forced into new channels to create complex fracture geometries.”

However, it is a bit of a hit and miss game, as the injection of the proppants takes place deep underground, and there is really no way to determine if the proppants have succeeded or are optimally placed because there’s no visibility into the process.

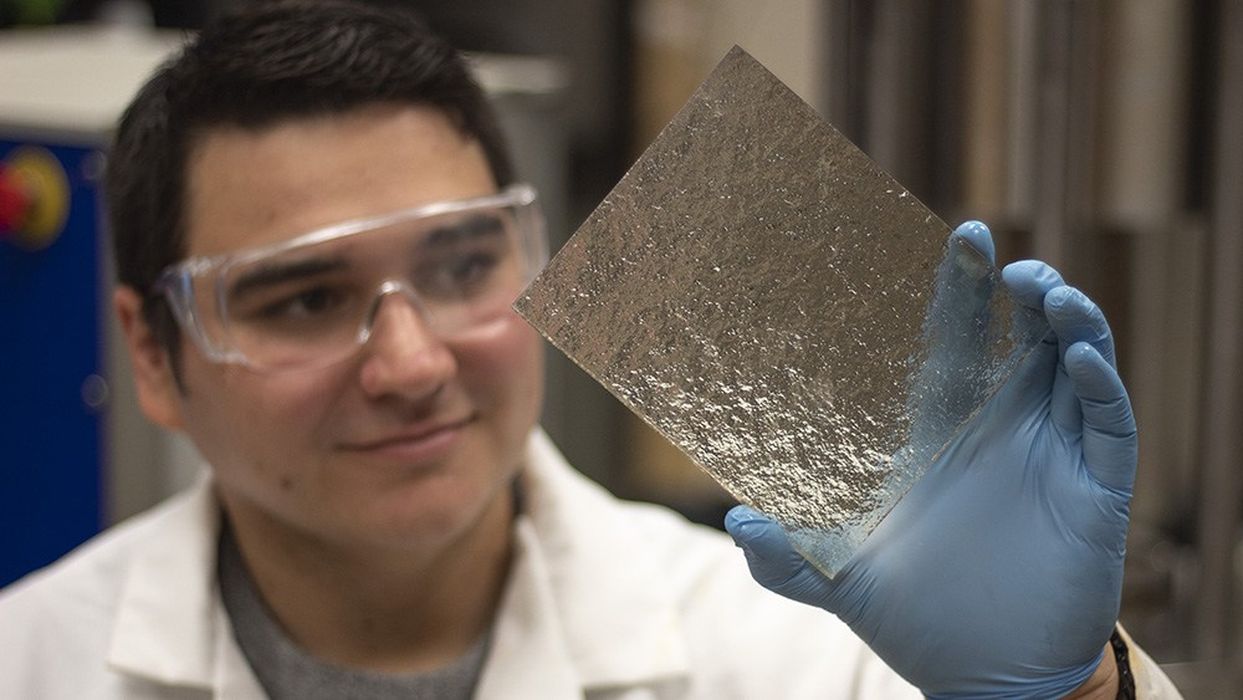

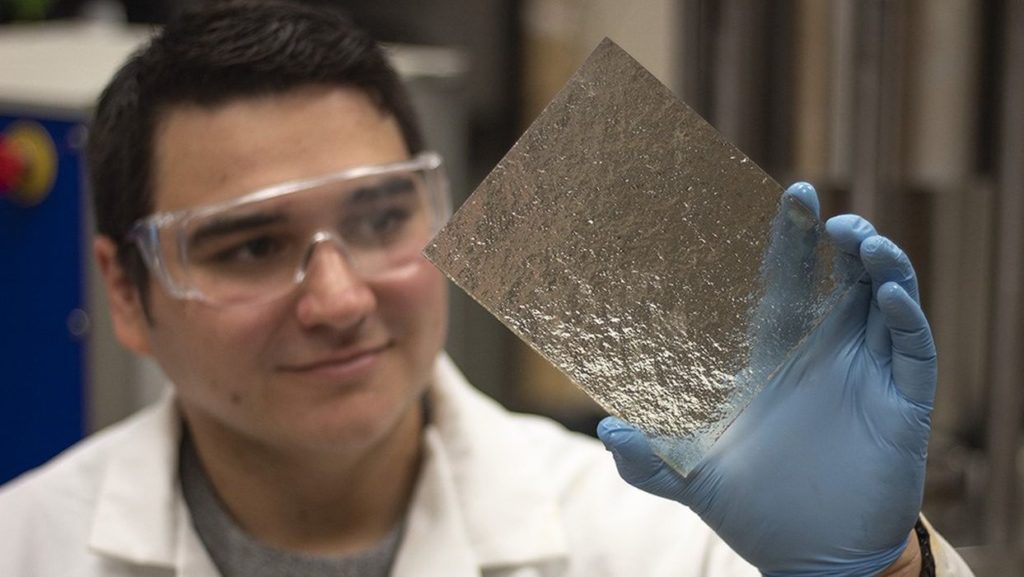

That can change with the work of Texas A&M University graduate researcher Gabriel Tatman, who developed a method of simulating this process using 3D printing techniques.

His idea was to prepare complex 3D models of a typical rock region based on data obtained from actual fracture scenarios.

The data-driven 3D model was 3D printed in a clear resin. The transparency allowed researchers to directly observe the movement of proppants through the simulated fracture volume.

3D printing allows the researchers to reproduce the fracture volumes in unprecedented surface detail. Because resin is a relatively fragile material, the researchers instead used these 3D prints as a mold to cast harder material (cement) that mimics the actual rock properties.

This process allowed the researchers to reproduce many identical copies of the sample volume. Experiments could then be performed iteratively using these copies to help develop more effective approaches for propane injection.

This is an unusual application for 3D printing that I haven’t seen previously: simulate that which cannot be seen. I have a suspicion there may be multiple analogous applications hiding in other industries.

Via Texas A&M