SPONSORED CONTENT

There’s always been a divide between the world of part production and the world of prototyping, but in recent times the gap between them is closing.

Plastic part manufacturing has been dominated by the injection molding process for decades, and for good reason: the process produces high quality parts with consistent dimensions and surface quality, and can be done for a very low cost per part.

This sounds ideal, doesn’t it?

It turns out there are a lot more twists to the story. When you look deeper into the injection molding process you quickly see a number of unavoidable constraints.

Injection molding works by first producing a negative mold of the part in metal. The process of creating such a mold can take weeks or even months, because the geometry typically has to be iteratively redesigned to ensure easy release of the part once the injected thermoplastic has cooled. The process of producing that mold can be quite expensive, often in the tens of thousands of dollars for each mold.

For a part with a complex geometry that must be broken up into several sections, there may be several molds required to account for part removal. This can make mold production even more expensive.

But once made, the molds can be reused thousands of times, each quickly producing identical parts at very low cost.

However, this isn’t the whole story.

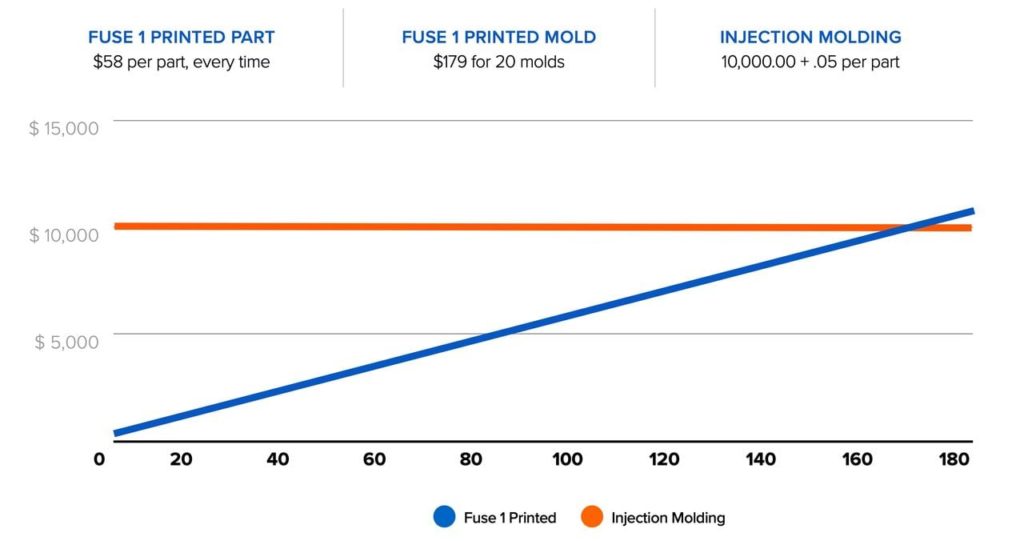

Yes, the cost of a single injection operation can be inexpensive, but the cost of the mold must also be accounted for. Usually this means that a portion of the mold cost is allocated to each part produced.

For example, if a mold cost US$10,000, and 1,000,000 parts were produced, then each part would be allocated US$0.01 to pay for the mold.

Adding a cent to a part seems like a trivial adjustment, and it is. But what happens when the amount of parts is lower? If we were to produce only 1,000 parts, then the allocation would be US$10 per part!

That might be ok, but not if it pushes the total price of the part over customer affordability levels. If so, then the part isn’t worth producing. In the worst case, a single part would have to pay the entire cost of the mold.

The result of this economic equation is that many parts required in smaller volumes simply are not made: it’s not worth producing them using injection molding.

Enter 3D print technology.

For many years that technology has been dismissed as a means of producing end-use parts for two reasons.

First, the cost of materials and production was considered high, as compared to the cost of injection molding. Secondly, the materials available to produce the parts were not optimal and suitable only for prototyping, again as compared to injection molding.

But hold on a moment, the first comparison is valid ONLY if the injection molding process is used for large volumes of parts. As we saw above, if the part volume is lower the cost of injection molding skyrockets.

What if you required only 10,000 parts? Or only 100? In those low volumes injection molding almost always is not an option.

3D printing can produce parts with a predictable price per part, as the cost of each print doesn’t change much from job to job.

Regarding materials, the materials constraints that limited 3D printing to prototyping applications have largely disappeared in the past few years, with today’s equipment able to handle a much wider range of powerful engineering materials entirely suitable for end-use applications.

It’s for these reasons that some manufacturers are gradually coming around to the notion that 3D printing could indeed take on low volume production jobs. Some manufacturers discovered this capability as a result of pandemic effects that cut them off from their usual sources of parts, forcing them to take a serious look at 3D printing techniques.

But having opened the door to production 3D printing, these manufacturers are rapidly discovering many more uses for 3D printing in their operations.

One key advantage beyond the financial aspects is the ability to tweak the design as production proceeds. Often new parts generate feedback from buyers. But if produced with an expensive injection mold, it’s usually not feasible to redesign the part. Meanwhile, it is a trivial matter to swap in a new design file for a 3D printer to produce a more advanced design on the very next production job. Production parts can improve easily with 3D printing, but far less so with injection molding.

In today’s rapidly evolving technology world, the ability to quickly change designs will become increasingly important. Companies “trapped” with large quantities of identical parts will find themselves less able to react to competitive pressures and new discoveries.

It goes beyond production parts for customers, as manufacturers, once open to the concept of low volume production, realize they have several low volume needs already hidden in their operation.

One typically found in manufacturers is the production of jigs and fixtures, which are typically used to aid the assembly of a complex product. These provide a means to quickly align parts as they are attached. Often these jigs and fixtures change periodically as the production line evolves or if someone happens to have a better idea for how it can be done. All of this is easily doable with 3D print technology, and is a low volume application on its own.

Another low volume application that is lesser known now, but surely will become a standard approach in future years is that of digital inventory. The idea is that instead of pre-making large quantities of spare parts for future use while you have the production line running, you instead just store the digital design and 3D print spare parts as required. This eliminates the need for warehousing and associated processes and greatly lowers the cost of spare parts.

One 3D print company that’s been strongly focused on this transition is Formlabs. The company’s new SLS system, the Fuse 1, is an ideal device to handle low volume production of many types of end-use parts whose production might otherwise be attempted with injection molding. The Fuse 1 is capable of reliably producing parts in PA11 materials with excellent strength and surface quality.

The company has recently published an extensive white paper explaining how several of their manufacturing customers have leveraged Fuse 1 technology to provide an alternative to injection molding processes for an expanding set of applications. It’s a fascinating read that should definitely be worth the time for any manufacturer considering the technology.

Via Formlabs