Tethon 3D obtained a patent for a key 3D printing feature in the resin process.

The Omaha-based company is known for their production of ceramic resins used in many different 3D printers, as well as producing their own desktop resin 3D printer, the Bison 1000.

But they’re primarily a materials company, as their resins far outnumber the printers on their product list. Today they sell unusual ceramic resins, including:

- Porcelite

- Graphenite

- Virtolite

- Ferrolite

- Flex ceramic

- Glass

- Alumina

- Mullite

- Castalite

And many more. I think you get the idea: they’re deeply into ceramic resins of all types. In fact they also offer a “custom” resin service where they can design a 3D printing resin to meet your engineering demands, if physically possible.

Their detailed work with resins has generated quite a bit of intellectual property around the science of resin-making, and it seems they’ve put that to paper with the acquisition of a new patent.

US patent 10,981,326 is the specific patent in question, entitled “Three-dimensional printed objects with optimized particles for sintering and controlled porosity.”

The patent’s abstract said:

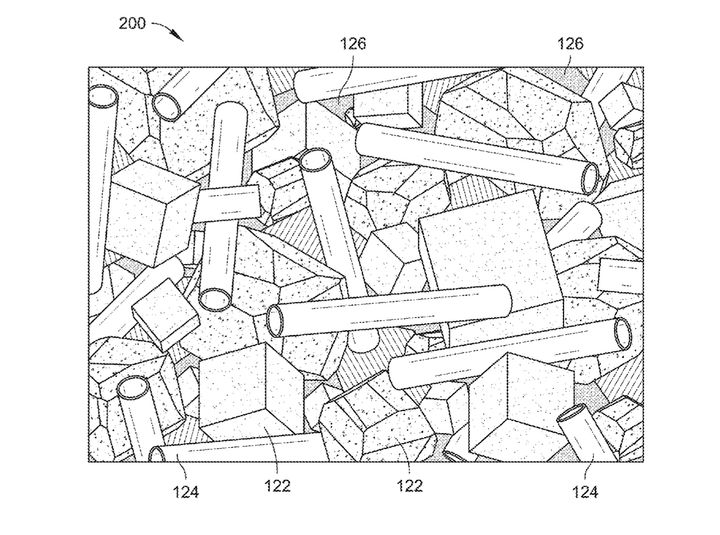

“A three-dimensional printed structure can include a photocurable resin, a sinterable material, and a plurality of elongated particles. The elongated particles are distributed within the printed structure. The elongated particles are shaped and distributed to promote porosity control (e.g., improved densification) within the structure.”

In the diagram here you can see how this works at a microscopic level. The larger elongated particles are used to develop the porosity mentioned in the abstract text.

But why would you want to increase porosity? Isn’t that a bad thing if you’re seeking to 3D print strong parts? Don’t you want a solid structure instead of a porous structure?

The answer lies in the nature of 3D printing ceramics from liquid resin. Let’s take a look at the basic process.

A ceramic resin fundamentally is a liquid photopolymer mixed with fine ceramic particles. As the 3D printer solidifies the liquid using UV light, the object takes shape. That’s the typical resin 3D printing process.

However, while a “normal” polymer resin 3D print simply gets washed and final-cured with some additional UV light, the processing of ceramic materials is a bit different.

The goal is to produce a true ceramic object, not one that’s a mix of polymer and ceramic, which is what comes off the printer and is known as a “green” part. That’s why the ceramic 3D prints here are post-processed using heat and/or chemical treatments. These will remove the polymer, leaving only ceramic particles in the same shape as the 3D print, albeit slightly smaller due to the loss of the polymer.

The final step is to sinter this “brown” part, which causes the ceramic particles to fuse together. At that point you’ve made yourself a pure ceramic object.

But there’s one tricky part: when the part is heated to remove polymer, the polymer essentially evaporates and is gassed off. That works fine at the surface, but what about deeper into the part? How does this gaseous polymer escape?

That’s where the porosity comes in. The elongated particles promote porosity, which allows the polymer to be more efficiently removed after 3D printing. This could speed up the post processing of ceramic parts.

And that’s why I think this is a key patent for Tethon 3D, as it would be desirable for any ceramic 3D print. Now I’m wondering which other resin companies use this approach.

Via Tethon 3D