I’m reading an interesting case study from Teton Simulation that illustrates an often-ignored fact of 3D printing: everything must work.

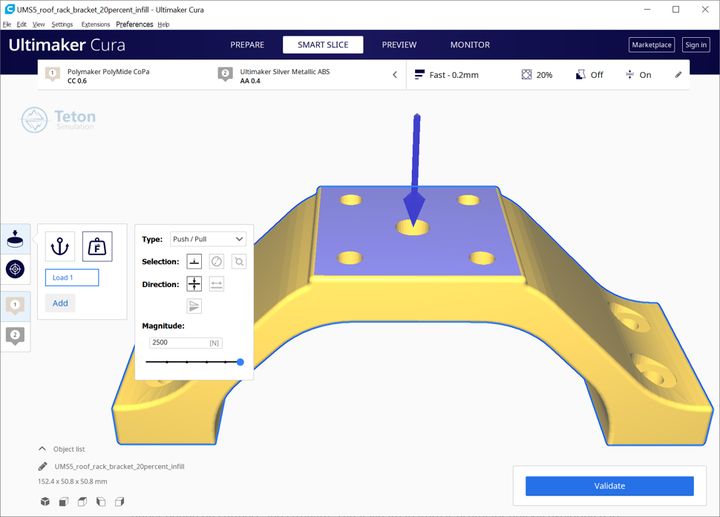

The case study explores how Teton Simulation used their advanced “Smart Slice” software to optimally prepare a print job using Polymaker’s new PolyMide CoPA material. Smart Slice is an Ultimaker Cura plug-in that integrates structural simulation, enabling it to adapt the slicing parameters and GCODE path generation to optimize for a specific usage scenario.

This is quite unlike other 3D print slicing software, which effectively ignore the simulation aspects. While some slicing software can allow an operator to tweak GCODE generation, say for example to increase the number of perimeters around holes, it is entirely manual.

In this case study Teton Simulation’s advanced slicing software is highlighted, but at the same time the study used Polymaker’s PolyMide CoPA material. It’s an advanced nylon 6 material that exhibits “no warp”, unlike most nylons, yet provides the other standard nylon engineering properties. You could say it’s an advanced 3D printing material.

Here we have an advanced material being prepared for 3D printing with an advanced slicing tool. That sounds like a great combination, but it is also indicative of the right way to think about 3D printing.

All too often users get hung up on one aspect of 3D printing when in fact successful 3D printing depends entirely on ALL factors being correct.

For a 3D print to succeed, all these things must be “right”:

- The material

- The slicing software

- The slicing parameters

- The environment (for open air 3D printers)

- The 3D printer itself

That’s why I am a bit fussed when someone suggests that a 3D printer always produces great output. It’s not the 3D printer that accomplishes that feat, it’s the combination of all of the above. A great 3D printer will choke on bad filament, or produce a terrible mess if the slicing is done improperly.

Just because a 3D printer has a slightly better resolution or a material has a slightly wider thermal range doesn’t mean a print job will succeed.

You must get EVERYTHING right in order to succeed in 3D printing.

These are not binary factors, however. They each have a spectrum of goodness to badness, making the scenario a bit fuzzy. There might be outstanding quality material, absolutely terrible material or anything in-between. The same can be said of the other factors.

Depending on your application needs you need to balance these factors together in a way that achieves your goals. For a rough print that will be used only once, perhaps you don’t need to pay as much attention to all the factors.

On the other hand, if you need to produce a mechanical part with the best surface finish, optimized weight-to-strength and do so reliably, then all factors should be optimized as far as they can go.

In Teton Simulation’s case study they’ve looked at two of these factors. To complete the optimization, a specific 3D printer could be added to the analysis, for example. The best results are obtained when you optimize everything.

Retired US General Colin Powell once said:

“You have to make sure you know why you are going to war and then use decisive force to end it as soon as possible.”

That’s true here, too: if you’re going to 3D print something, strengthen all of the factors involved.

Via Teton Simulation