I’ve had a problem with 3D software tools for many years, and it’s time to write about it.

The problem lies in the viewing systems of these tools.

For 2D tools, setting up different views of the document are easy: you scroll up or down. Everyone knows how to do that, and about the only thing that differs is what the up and down arrows look like. Regardless of the 2D system, it’s almost always intuitive to figure out how to get the view you want of the 2D document.

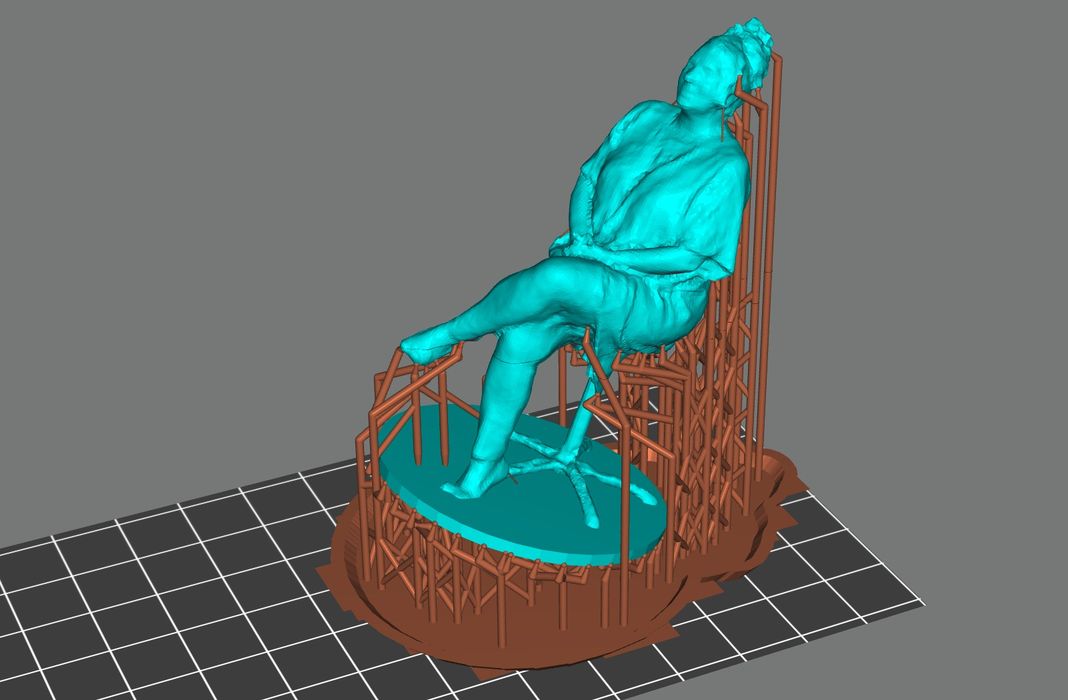

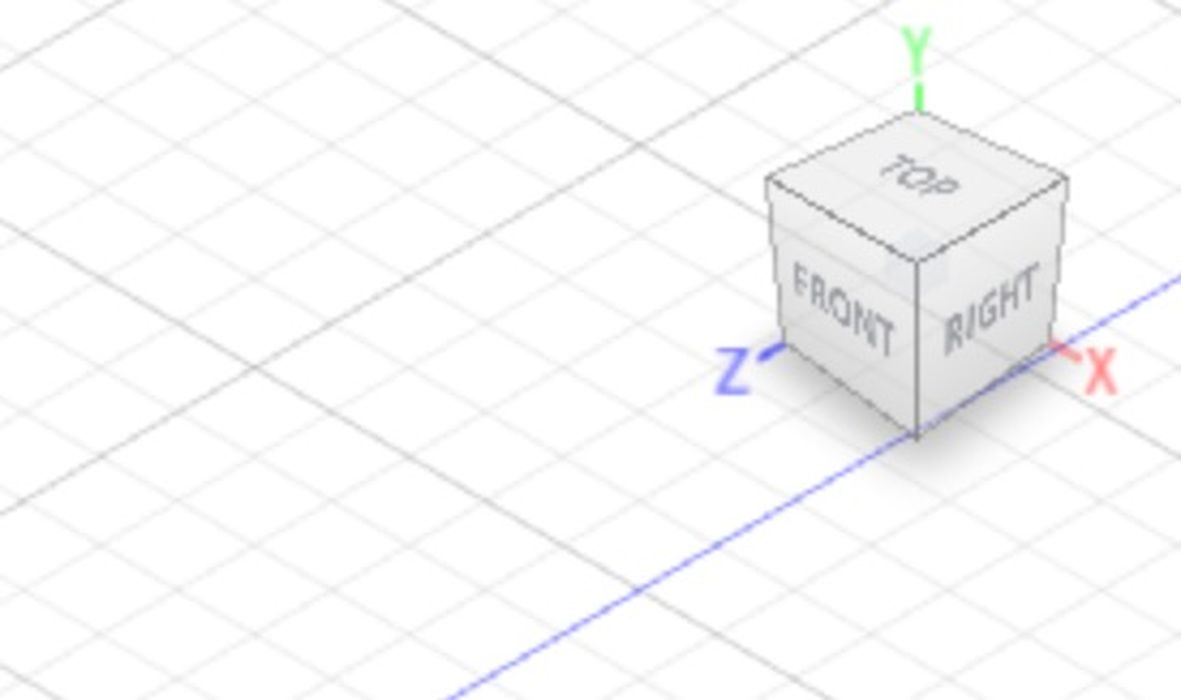

3D tools also have documents, but they add another dimension, thus complicating the viewing system.

All 3D systems should provide these viewing capabilities:

- Zoom in or out

- Spin the view in any of four 2D directions

- Pan the view in any of four 2D directions

That’s it, that’s pretty much all you need to organize the optimum view of your 3D creation.

I use many different 3D tools. Some are for creation (and I use different tools for different types of creations), some for model repair, some for model inspection and adjustment, some for job preparation, and so on. Come to think of it, I probably use around a dozen 3D software tools on a regular basis, mostly because there is no single tool that does everything.

I strongly suspect most Fabbaloo readers are in the same boat: we may use different 3D tools, but we all use combinations of several in our normal workflows.

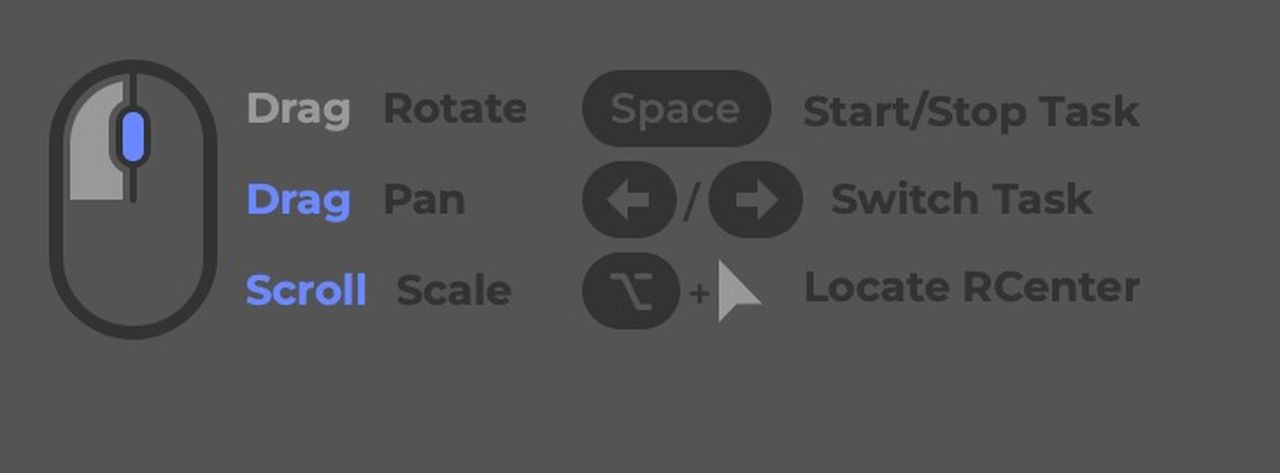

The problem is that almost all of these tools use slightly different methods of controlling the 3D view for the three basic functions above.

As I move between tools, I constantly mix up which method is required for the current tool. Is it “Shift Left Click” or “Right Click Drag”? Nope, it was “Option Control Left Click Drag”. Even worse, some combinations do one function in one tool, but a different function in another. Oops, I zoomed instead of panning.

I might be using one tool frequently for a week on a project, and then switch to a different tool later, only to “forget” which key stroke combinations are required. And good luck if you haven’t used a tool for a few months.

Most tools don’t have any visual cues to remind the user how to alter the view, and merely assume that you “know”. I can’t tell you the number of times I end up search for “how to view” for various tools as a reminder, and that’s really inefficient.

Another complication is hardware. Some tools assume you are using a three-button mouse with a scroll wheel. But are you? On my MacBook the mouse looks a little different. What if you are using only a trackpad? What if you are on a tablet using your finger?

More searches inevitably ensue.

One viewing tool I really like is 3DConnexion’s set of 3D mice. With the twist of your hand, you can zoom, move, twirl or more so easily. In a 3D environment you can very quickly learn how to “fly” into any viewpoint you require almost instantly. This should be a mandatory feature for every 3D tool.

However, it is not. In fact, 3DConnexion supports only a few tools, and specialized drivers are required. Frequently this support breaks when new versions of the software are issued, and they you’ll have to wait months for an update.

So that’s not a solution.

What could be a solution?

I would like to see 3D software producers somehow agree on a standard convention for 3D viewing controls. That means a very specific set of keystrokes for the above functions, and also for alternate hardware including fingers, trackpads and 3D mice.

Of course this is not going to happen. There are far too many 3D software producers to ever hope they could organize a simple standard of this type.

But I do feel a lot better having ranted about this issue.

How do you feel about 3D viewing controls? Let us know in the comments.

I use Rhino3D. It has the most intuitive interface short of TinkerCAD (dont laugh its really good at certain things), of course it’s rigid. It’s a surface modeler. This carries with it inherent downsides for anything with a complex internal geometry. But yeah, I’ve tried blendr and zbrush and threw it out the window within a few minutes of trying anything remotely simple. If the biggest barrier to using your program is the program, something is wrong.