Controversy has erupted over Sprybuild’s new continuously operating resin 3D printer.

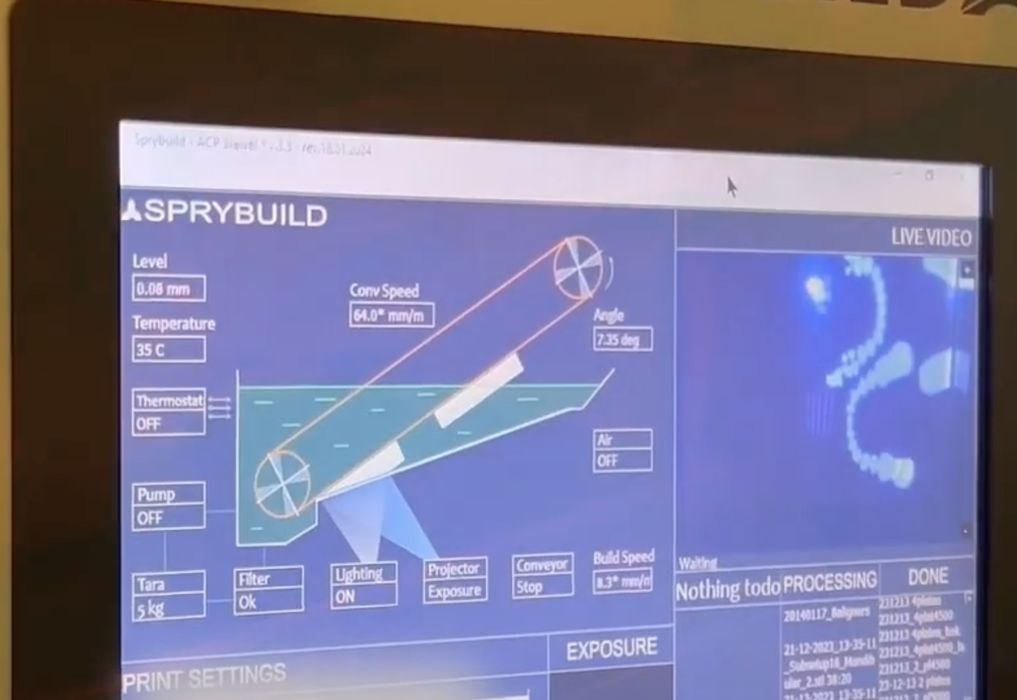

The device, announced a few weeks ago by the Israeli company, uses a conveyor belt system to implement their 3D printing concept. The system uses an angled light engine to produce layers during printing. The belt then moves the object ahead slightly, where second and subsequent layers are produced.

Eventually the object is complete and it continues to the end of the belt. There, the belt sharply turns around, but this curvature causes the print to peel off and fall into a collector basket.

This would allow continuous production of resin prints. But to clarify, there are some resin printers that might be considered “continuous”.

These would be continuous DURING a print; they don’t have a layer delay to peel off the vat and wait for resin to flow in. However, at the conclusion of the job you still must manually remove the print and reset for the next job.

The Sprybuild system is different in that the conveyor belt concept allows a series of jobs to run one after another without operator intervention. That’s a highly desirable feature for production operations.

This all sounds great, except for one thing.

There may be a patent issue forthcoming. In a post by noted 3D print designer William Steele, he writes:

“Hmmm… where have I seen this before? Oh, yeah, that’s right… in my patent!”

If you take a look at Steele’s 2017 patent you will immediately see a number of suspiciously similar elements.

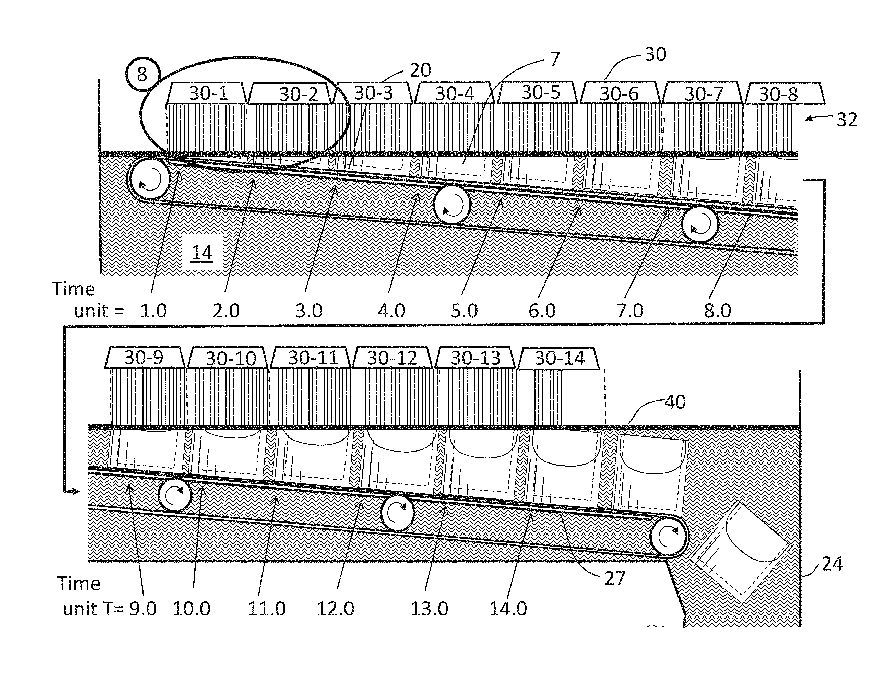

Steele’s system uses a conveyor belt, and has multiple light sources to build objects all along the belt. In this image you can see how it is supposed to work.

Sprybuild replied:

“To make a correct conclusion it is necessary to compare technologies. Some external similarities are not enough”.

Is Sprybuild correct? Or does the design infringe on Steele’s patented design?

There are a number of similarities, but there are also some differences. Sprybuild seems to use one light source, whereas Steele’s uses multiple sources in parallel. The Steele approach might achieve more throughput because of that difference.

Another difference is orientation. While both systems have components submerged in resin, Steele’s light engine(s) are on top, while Sprybuild’s are shining through the bottom of the tank.

I’m no patent lawyer, but I do know that patents tend to be written in generic fashion to allow for some variation in design. That would enable them to cover similar approaches. However, I also know that seemingly similar designs are sometimes considered unique by the legal process due to minor differences.

Are the differences above (and likely a few others that won’t be known until the details surface) sufficient to convince a court that the designs are truly different?

That all depends on what happens next. While Sprybuild is continuing with their product launch, it’s up to the patent owner to launch an infringement lawsuit.

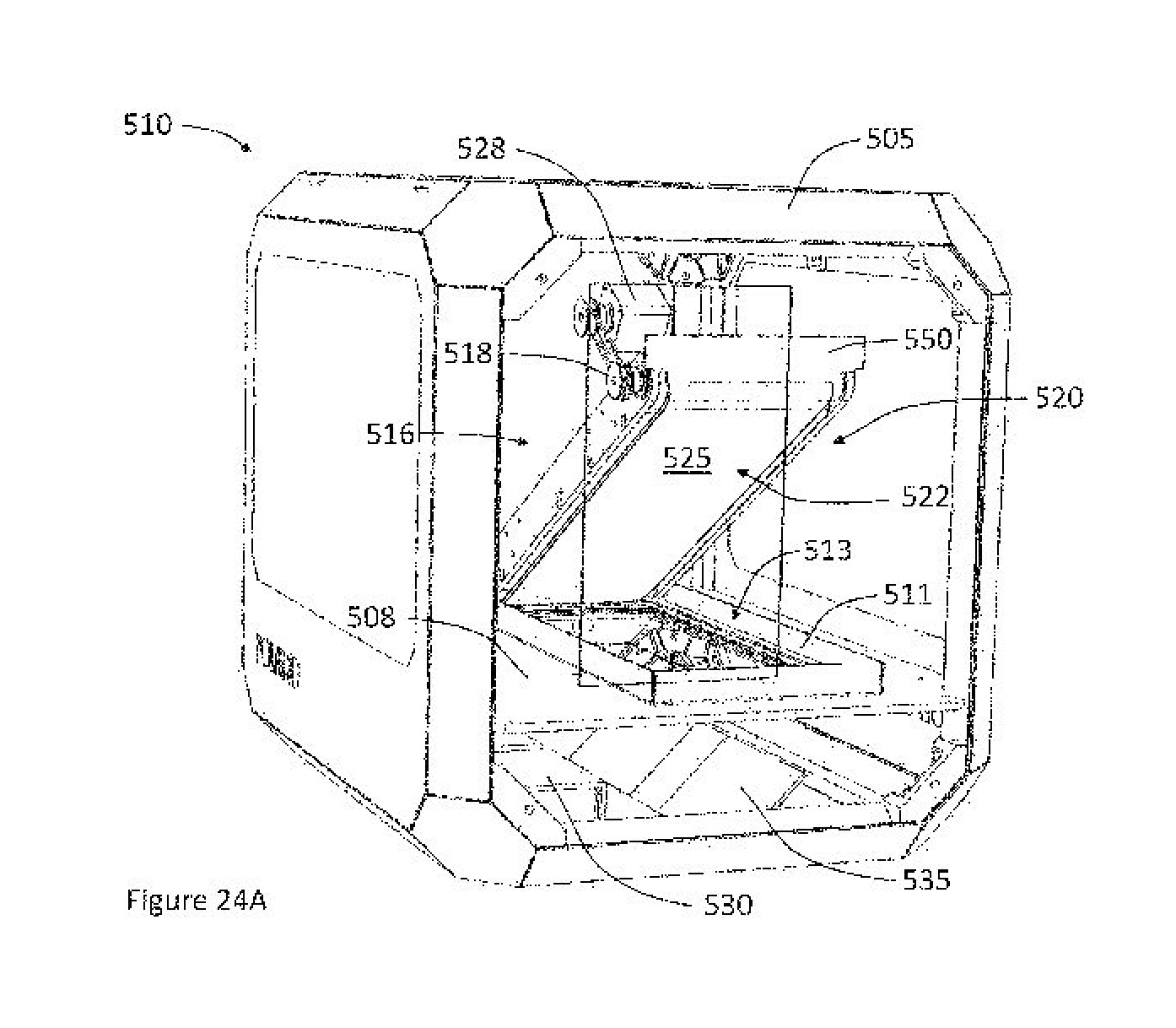

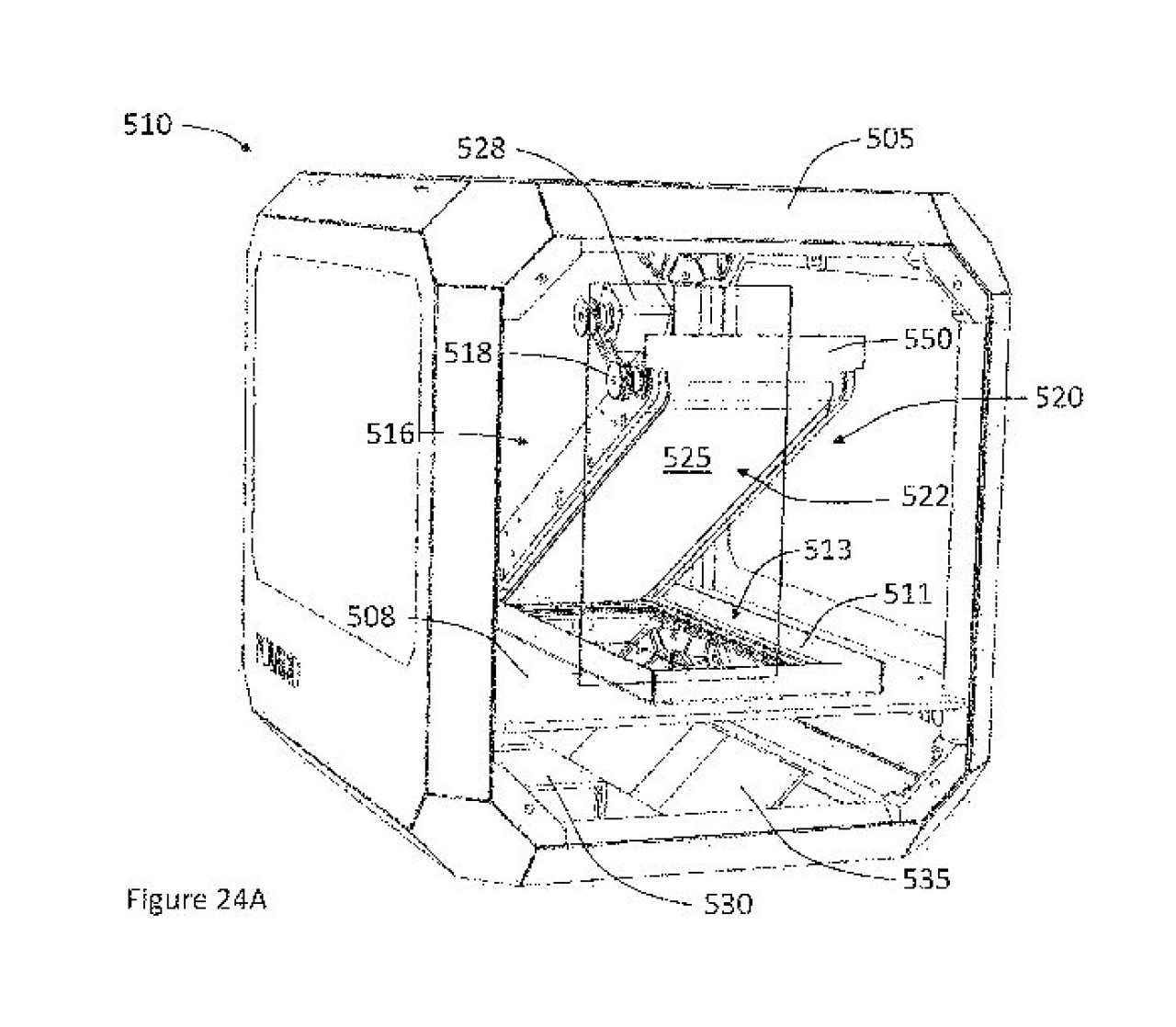

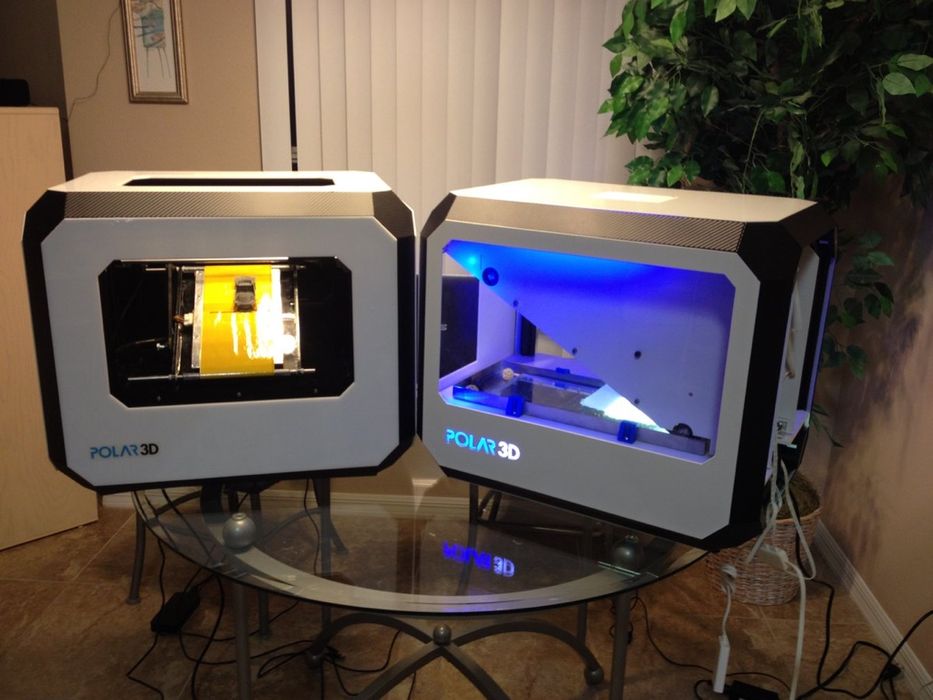

According to the patent, it is currently assigned to POLAR 3D LLC by Steele. Polar 3D is a company we first encountered in 2015, when they marketed a small “polar” style 3D printer with a unique rotating build plate. That didn’t take off, and the company now offers a 3D printing cloud service.

In a photo posted by Steele, it’s clear that Polar 3D actually built a 3D printer using this process.

Will they be willing to launch a lawsuit against Sprybuild? We can’t know because the decision would involve internal decisions at the company.

Should they decide to move forward, it will be a very interesting technical analysis of two similar 3D printing processes.

Via Sprybuild, Polar 3D and Google Patents