If you’ve ever wanted to 3D scan and print very tiny things, the scAnt 3D scanner is for you.

3D scanning systems are typically designed to handle a specific range of object sizes. A 3D scanner set up to handle shoebox-sized items usually won’t work for 3D scanning a building, and vice versa.

Most of the 3D scanners I’ve used have a lower limit to their capabilities; if smaller objects are scanned, they turn out “blurry” and poorly formed. That’s because the resolution of the scanner — be it structured light or lasers — can’t resolve any further details.

There is a way to achieve far smaller resolution levels, and that’s by using photogrammetry. Photogrammetry is the process of taking a series of images from all angles of an object and then using sophisticated software to knit them all together into a 3D model.

Sounds easy enough, but photogrammetry is actually quite challenging to do. While the software part is relatively easy — you just load in the images and let it run — the hard part is to collect suitable images. The images must:

- Be very numerous, over 200 at the very least to obtain proper details

- Be equally illuminated from all sides, top and bottom

- Not have shadows anywhere on the subject’s surface

- Be of identical focal length

- Be in focus

- Have a crisply focused background

You get the idea; it’s really hard (and tedious) to do this.

For small objects some have produced “scanning rigs”, which are essentially tabletop devices that slowly rotate an object in front of a camera. This provides a way to more easily automate the capture process and obtain proper images.

That’s essentially what the scAnt does, except that it’s specifically designed for very, very small objects — like ants. I wasn’t kidding when I said the scAnt is a scanner for ants.

scAnt 3D Scanner

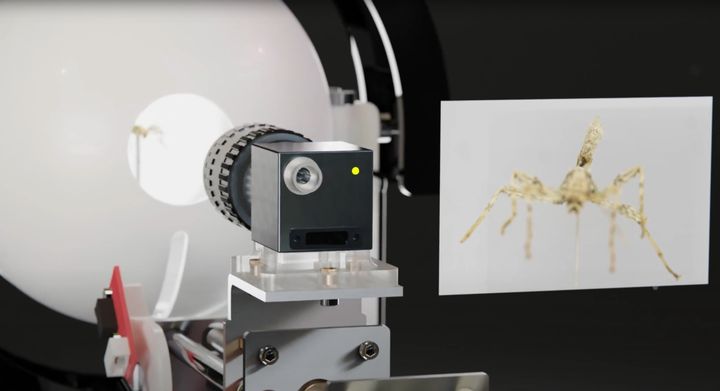

Unlike many of the typical tabletop 3D scanners, the scAnt includes a 360 degree photo booth. The subject is surrounded in a spherical capsule that’s brightly illuminated on the inside.

The subjects are impaled mounted on a needle at the center of the sphere, which allows illumination of the bottom as well as the top and sides. This setup should provide an ability to capture images of outstanding quality and resolution, perfect for photogrammetry.

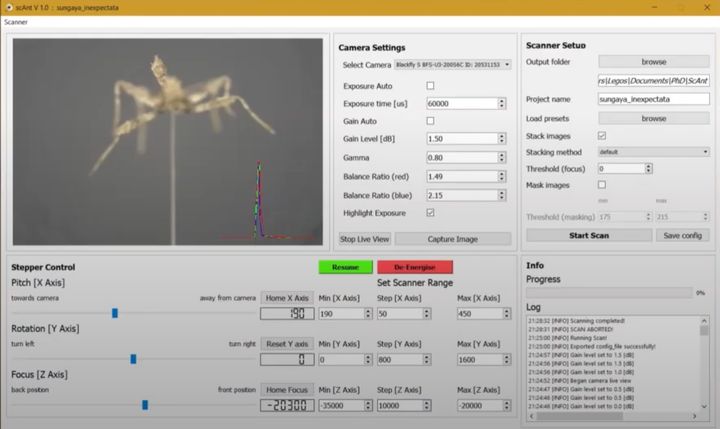

The scAnt provides a means for rotating the object on two axes. This provides a way to expose each surface area to the camera hole. Outside the hole will be a suitable camera that can rapidly capture images as the “ant” is twirled around.

It’s even possible to plan the rotation sequence to ensure you capture all relevant surfaces, even in a problematic shape.

This arrangement allows one to easily capture extreme details on very tiny objects. The objective of the developers was to provide an easy way for museums and researchers to capture 3D models of insects, which up to now have mostly been digitally captured only in 2D form.

Additionally, they believe the capture of insect 3D models could be used for future AI recognition systems that would compare 2D field work images to instantly identify the critters. They have other potential applications in mind, too.

If this has got you excited, I’m afraid you cannot purchase a scAnt 3D scanner. That’s because it’s an open source project — you can build one yourself at a very low cost.

The parts are all easily obtainable and 3D printable, as they’ve posted the necessary 3D models on Thingiverse. As well, they’ve posted the necessary software on GitHub so that you can drive the scanner when you’ve built the hardware.

I fear we may see some rather large and scary 3D printed ants very soon.

Via YouTube, GitHub and Thingiverse (Hat tip to Phil)