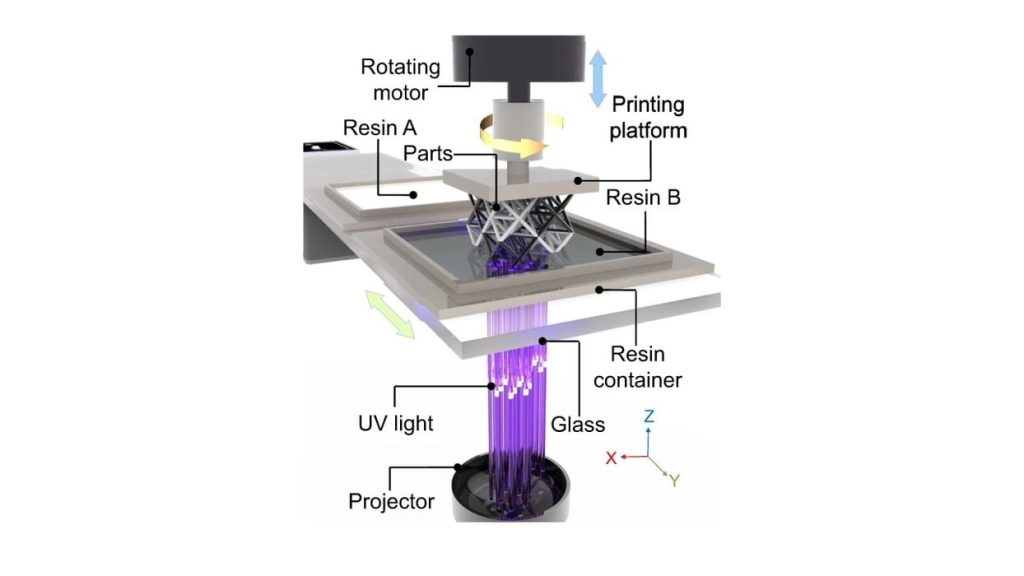

Researchers have developed a new way to 3D print resin in multiple materials using centrifugal force.

The new process, called Centrifugal Manufacturing, or “CM”, overcomes one of the biggest challenges in 3D printing: multimaterial resin printing.

Resin is a powerful 3D print material, as it can be mixed with other substances to create a very wide variety of material types, including polymers, high-temperature thermosets, ceramics and even metal.

But you can’t mix them in the same print job. The printer’s vat contains only one resin at a time. It is possible to mix resins, as I did when testing the Carima CMYK resin set the other week, but really you’re only printing one material at a time.

That has greatly constrained the use of resin 3D printing, because many parts can benefit from having more than one material or color.

Now researchers have figured out an ingenious method for allowing multiple resins to be used in a single 3D print job, and it’s one of the most fascinating processes I’ve ever seen in the industry. Here’s how it works:

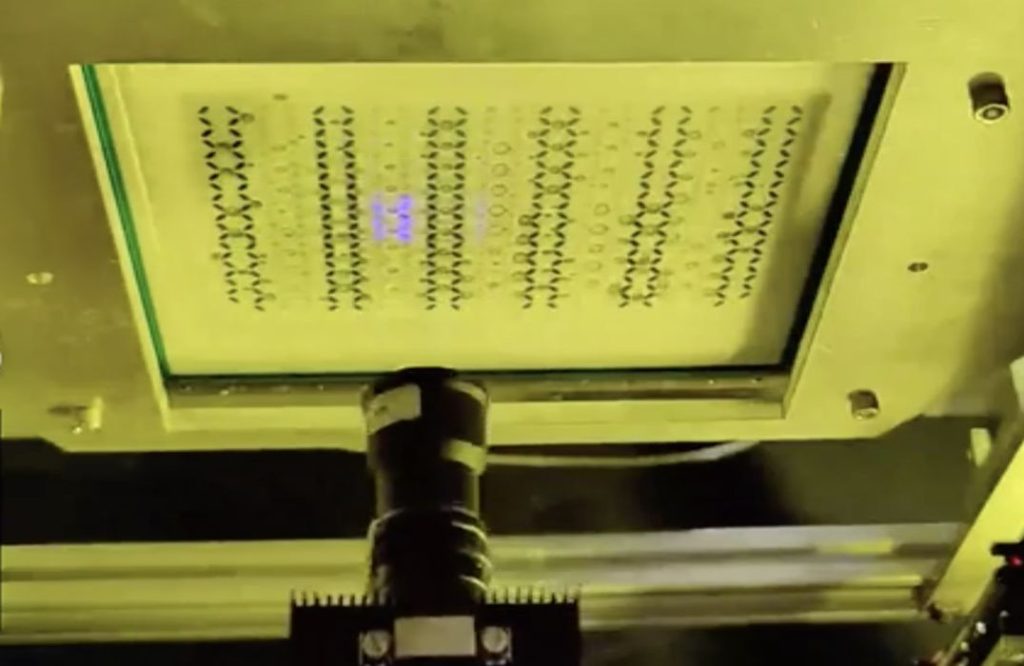

- A layer (or portion of a layer) is produced in the usual fashion: UV light from below polymerizes a portion of the build plane

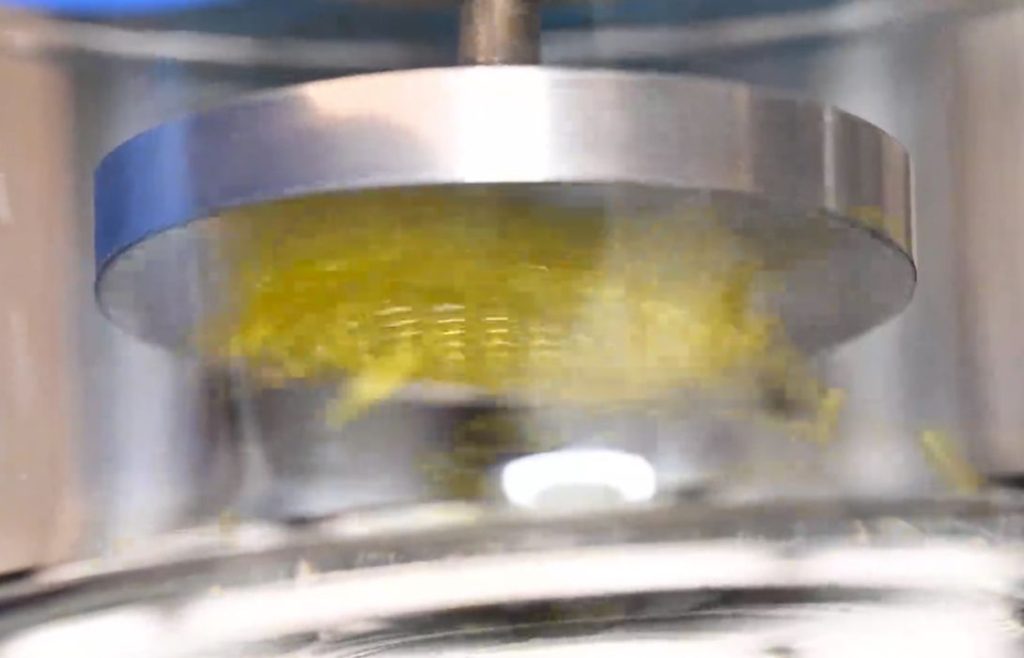

- The platform is raised up above the surface of the resin

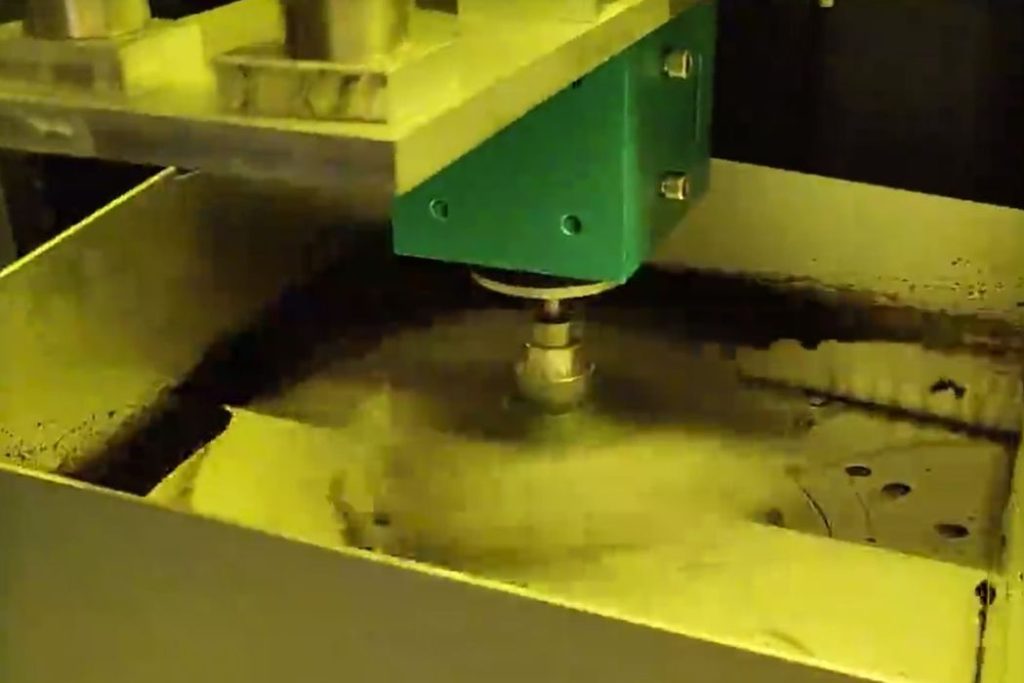

- The platform is rotated at high RPM (something between 1,000 to 10,000 RPM, depending on the resin material)

- The centrifugal force pulls off the wet print, leaving it clean of stray resin

- A second (or third or fourth) resin tank is shifted under the print

- A new layer (or portion of a layer) takes place in the usual fashion

- The process repeats until the object is complete

At first I was quite skeptical of this approach. I had several questions, including “wouldn’t loose resin get trapped in pockets?”, “what if the resin is viscous?” and “where does that spray of resin go?”

The researchers provided answers.

The pocket problem doesn’t really exist: only the very bottom of the print is wet by resin, so there’s not much to pull off. Also, upper layers are repeatedly spun as each layer completes, yanking off any remaining resin.

The researchers tested several viscous resins and determined that the approach does work; you just need to spin the platform faster.

They did discover that when printing softer materials, like elastomers, that the print itself could distort due to the rotational forces. However, this was rectified by spinning slower for those types of resins.

One problem that doesn’t exist in conventional resin 3D printers is balance, which does exist in CM printing. It would be possible to print an object that is off-center on the print plate. When it is spun you’d get a very wobbly result, possibly damaging the machine. To counteract this, the software must generate and print “counterweights” that appear on the build plate and compensate, much like you’d do with automobile tires.

The results are extremely impressive. They were able to 3D print objects with very crisp color transitions, suggesting that the stray resin is truly removed by the centrifugal force.

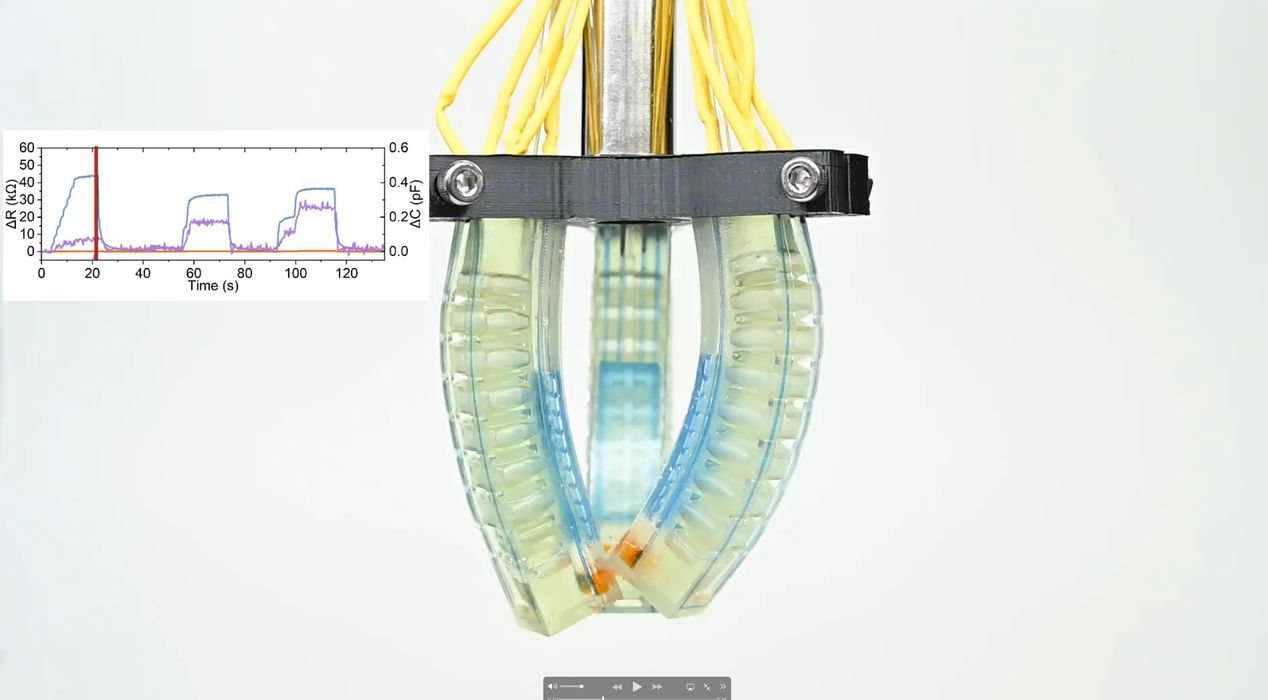

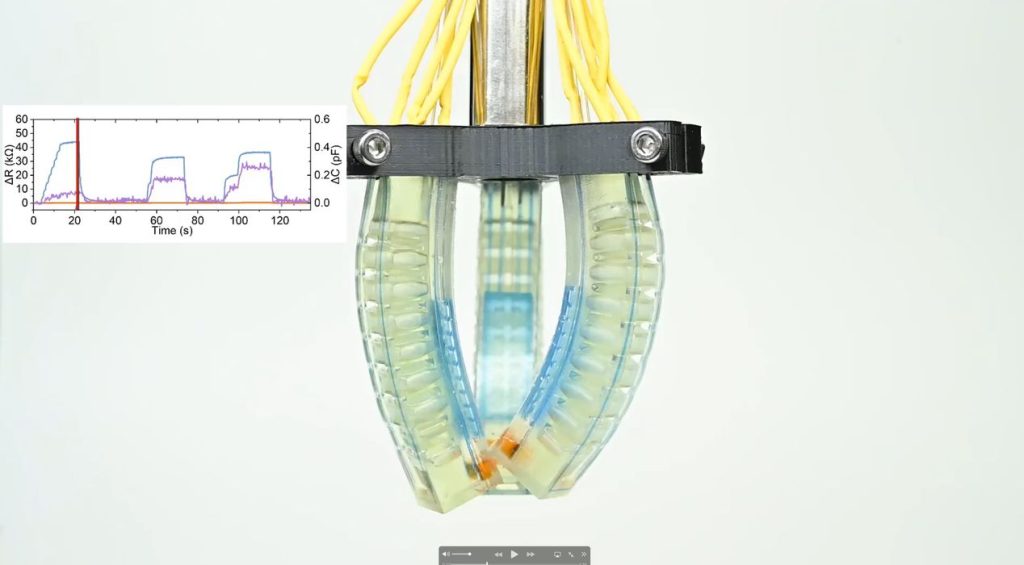

One complex print performed was to produce a soft actuator for robotics. This used a combination of hard and soft materials in the same resin print job. This demonstrates the versatility of this approach, and would put resin 3D printing on par with FFF 3D printing’s ability to use multiple materials.

Two issues that may be present with the CM approach are time and cost.

Unless the spun-off resin is recovered, it’s likely more materials would be used to produce the part than with conventional methods. Also, the need to print counterweights would also take up more materials.

The print time on this system could be significantly longer, as each layer would require up to 10 seconds of spin and movement. That’s vastly greater than the peel process used by many systems today and infinitely longer than no-peel printing processes such as Carbon’s.

Nevertheless this is a fascinating process that will surely be commercialized sooner or later.

Via Nature