Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have developed a 3D printed “body on chip”.

This is quite an unusual application for 3D printing, and it takes a bit of explanation to understand what’s going on.

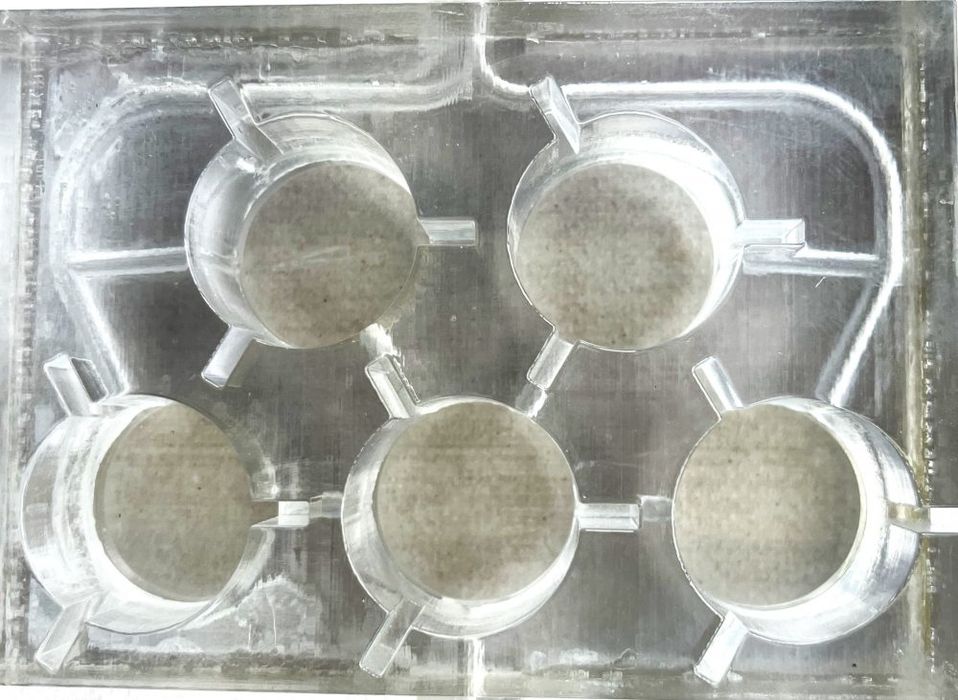

The tiny chip is shown at top, and you can see five different cells in the structure. These are interconnected with microscopic 3D printed pathways in which fluids may travel.

Each of the cells represents a different body organ: there is a cell representing each of the brain, kidney, liver, heart and lungs. The idea is to provide a platform to simulate how drugs move between different body organs. The body on chip is designed to mimic the human circulatory system.

Why do this? The issue is in the ethics of drug testing. Obviously, new drugs cannot be administered to even willing test patients without some assurance they are not harmful. Typically this is done by testing drugs on animals that have similar metabolisms to humans.

This is considered a cruel practice by many, but unfortunately it can’t be avoided without abandoning a considerable amount of progress in the development of new drugs. The new body on chip won’t totally solve that problem, but it demonstrates a path forward to reduce animal-based drug testing.

According to the University of Edinburgh, some 80,000 animals are used in early-stage drug testing in Europe each year. That’s only a portion of the testing that takes place worldwide, so you can see the scale of the issue.

Dr Natalie Duggett, NC3Rs Early Career Programme Manager, said:

“Liam’s body-on-chip device has the potential to replace a significant number of the animals currently used in safety testing across a range of industries. It is fantastic to see one of our PhD students awarded funding at this early career stage. This additional funding from the MRC recognises Liam and the CVS team’s pioneering work to transform drug testing in a human-cell based model and the importance of finding alternative approaches to replace animal use in these studies.”

What’s even more interesting is that the “on chip” concept can be extended. In addition to drugs, it would also be possible to test other substances, such as food, cleaning agents, industrial substances, aerosols and more using the same setup.

It would also be possible to create additional cells to represent even more body components to broaden the testing.

It just may be that this development has created an entirely new niche for medical research, powered by 3D printing.