Researchers at the University of Nottingham have made a breakthrough in healthcare 3D printing.

They noted a persistent issue in the printing of implantable parts in the healthcare industry. It turns out that implants frequently require multiple functions as well as a host of engineering requirements that are difficult to obtain in a simple 3D print.

Dr. Yinfeng He explained:

“Most mass-produced medical devices fail to completely meet the unique and complex needs of their users. Similarly, single-material 3D printing methods have design limitations that cannot produce a bespoke device with multiple biological or mechanical functions.”

Why is this so? It’s because most devices capable of producing biocompatible parts use a single material. While general purpose 3D printing doesn’t have a problem with this because the parts are used for mechanical purposes, it’s a big issue for medical devices.

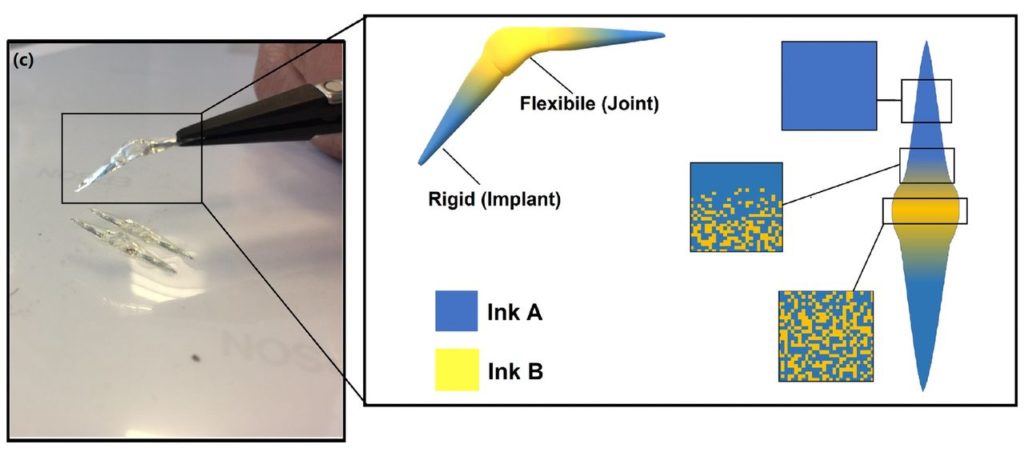

Consider the problem of a replacement finger joint. This is an item that must be both rigid (to attach to the nearby finger bones) and also flexible (to allow the finger to bend). This requires two materials, and conventionally-made replacement joints typically involve both metal and silicone combinations to achieve this, but the result is, well, a bit mechanical.

The new approach is called “MM-IJ3DP”, and involves generating a voxel-by-voxel 3D model that gradually blends rigid and soft materials together.

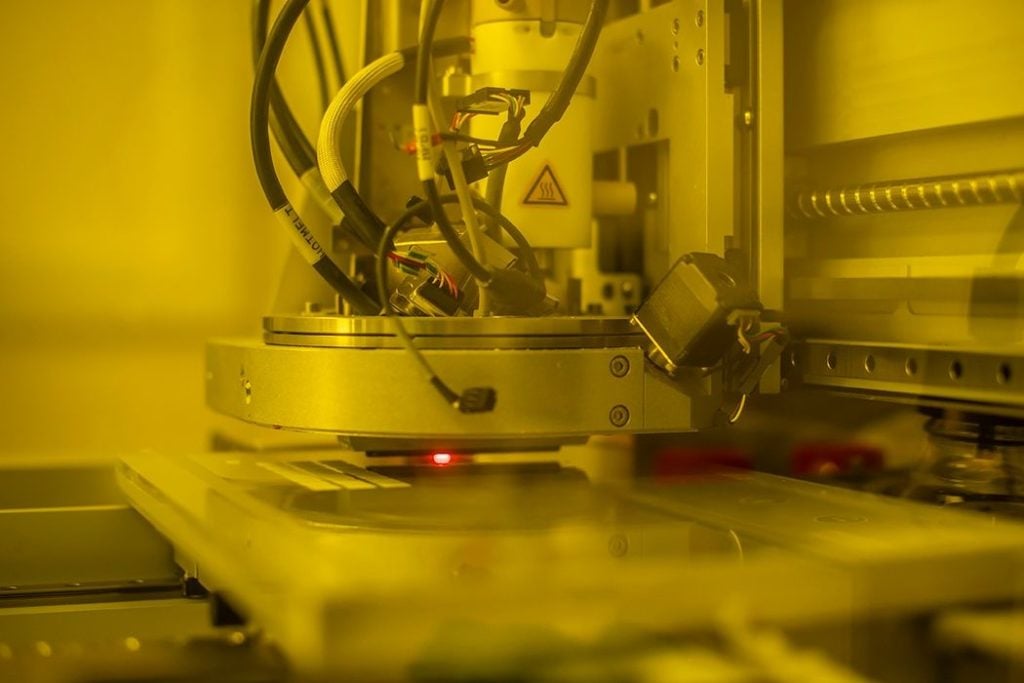

The 3D printer used for the experiment was a PiXDRO LP50, which uses dual print heads, each with 128 inkjet nozzles. This device uses UV light to cure selectively deposited photopolymers, much like other jet-style 3D printers.

The magic here, however, is in the complex formulation of the materials used in the 3D printer. The researchers were able to develop materials that exhibited differing levels of flexibility and at the same time were biocompatible.

This allows them to produce a patient-customized 3D model that is much more natural in operation with both strength and flexibility. Because of the voxel-by-voxel blending, the rigid and flexible zones are far less likely to separate. Shown here is an example of this type of 3D printed finger joint:

A side benefit of their approach is a level of safety as they were able to use materials that were “intrinsically bacteria-resistant”. This lowers the need for patients to take anti-bacterial drugs after implantation.

The finger joint example is only one possibility opened with this new multimaterial technique. Another suggestion is to use the system to 3D print “smart pills”.

These would be complex 3D designs where layers of material could dissolve in predictable durations, thus allowing the creation of a pill that would periodically release medication on a timed schedule. That’s something that I don’t believe exists today.

I believe this is a key development that will no doubt power a number of future healthcare applications, even beyond those mentioned by the researchers.

Via Wiley