You probably haven’t heard of Mantle, and that’s because they’ve been in stealth mode until this week.

The San Francisco-based company finally revealed what they have been doing in their secret labs, and it turns out to be quite interesting. They have created a unique 3D printer that can produce metal objects at low cost, with high quality and at high speed.

That’s quite a feat, and it’s due to their newly patented 3D printing process, which is a combination of familiar approaches that have been linked in a new sequence they call “Trueshape”.

Today, competitive metal 3D printing systems follow one of two paths:

- High-energy selective melting of metal powder beds, offering great results, but requiring a ton of post-processing and plenty of cash (example EOS); or

- “Cold” extrusion of pastes or filament made from metal powder and binder that must be sintered after 3D printing; it’s a low-cost approach, but also doesn’t provide the best quality parts (example Markforged)

Mantle’s process is unlike either.

Oh, I should mention, there’s one other variation that’s often seen in metal 3D printing: combining traditional CNC machining and metal deposition. There are several vendors that market systems that can either:

- Complete the surface finish on a rough metal part after 3D printing by adding a CNC mill; or

- CNC mill smooth the edges on each 3D printed layer during the print

Both of these result in high-quality metal parts, but the equipment cost is expensive because you not only have an expensive metal 3D printer, but also an expensive CNC machine, too. Even worse, those systems that CNC after printing can only handle certain geometries.

Mantle’s Trueshape 3D Printing Process

Back to Mantle.

Mantle actually combines several of these steps together into an entirely new process. Here’s what happens in Trueshape:

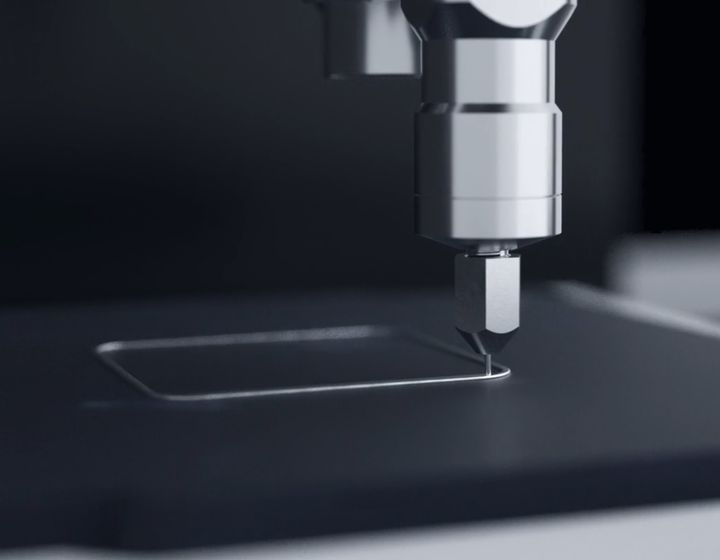

- Mantle first 3D prints the rough object by extruding a proprietary metal paste, much like the inexpensive metal 3D printer vendors do with filaments (see image at top)

- Each layer is exposed to heat to remove the liquid, leaving only metal particles and a small amount of binder

- While printing, a precision CNC mechanism mills the edges and surfaces smooth every few layers (see image above)

- The finished 3D print is sintered in a furnace at up to 1300C to burn out the binder and fuse the metal particles into a solid object

In other words, they are combining the “cold” metal printing process with a hybrid CNC approach. The CNC part should be easier because the print will be far less strong than deposited metal, and I expect the cost of their CNC components to be less than the full-metal competitors.

The materials are provided in a paste, which is a mix of a binding liquid and particles of different types, including metal particles. They call this “FMP” or “Flowable Metal Paste”. Mantle says other particles can be used to enhance surface finish or exhibit other properties. So far, Mantle has developed two proprietary materials:

- P2X, which “acts like” P20 tool steel, but with better abrasion and corrosion resistance

- H13, which “acts like” H13 tool steel, but can achieve greater hardness

It’s very likely they are developing additional materials in their labs at this moment.

Mantle 3D Printing Advantages

There are some particular advantages to this approach:

- It’s inexpensive because there are no fancy lasers

- It’s simpler because there are fewer thermal considerations during printing

- It produces precision parts because they are CNC milled to the desired geometry

- The quality is sufficiently high to remove the need for post-processing in many cases

- It is faster because there are fewer steps, and I suspect it’s much faster to initiate and complete a print, too

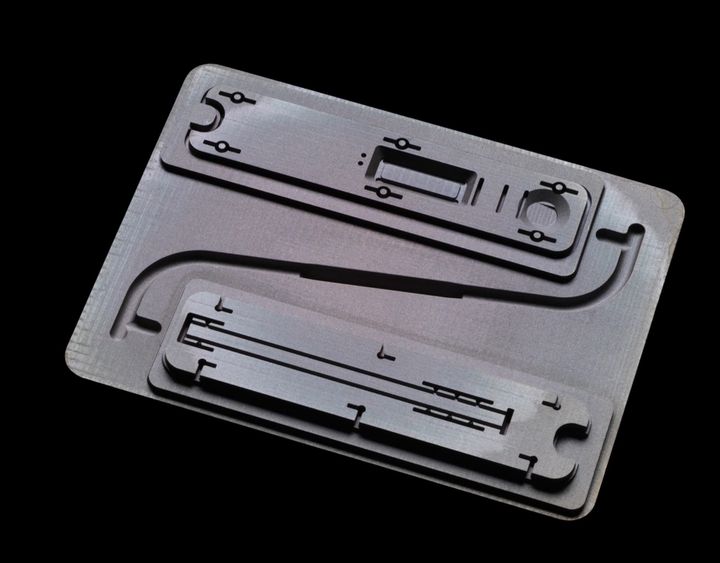

Part images provided by Mantle show very high-quality parts, and they say there was no post-processing required. This is quite important, as the cost of post-processing is one of the major cost components, mostly due to the requirement for manual labor. It seems that Mantle has chopped that part out of the cost equation.

The result appears to be a system that could operate at low cost, as compared to competitive systems that can produce similar part qualities.

Mantle provided a comparison chart showing their part can achieve an accuracy of 0.1mm over a 100mm part. This is particularly impressive when you realize the sintering step will reduce the part’s size somewhat as binder is burned out.

Other systems typically have parts shrinking up to 20% during de-binding and sintering, and so Mantle must have some interesting software to predict and account for this shifting for a given geometry. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t be able to reliably achieve that accuracy.

Mantle Questions

However, I do have some questions.

While I expect the cost of the machine itself to be relatively low as compared to traditional powder-bed laser systems, there is the matter of materials. Metal powders for 3D printing are notoriously expensive, and this could create financial space for Mantle to charge heavily for their proprietary metal pastes — which are certainly the only materials allowed in the device. It will be interesting to see Mantle’s material prices.

Another question is related to geometries. Mantle specifically suggests their system for 3D printing metal dies and molds, which are obviously great applications. But when you look at their sample parts, it seems they all have relatively simple geometry. There are no overhangs visible on any of their parts.

Does this mean the system cannot handle overhangs? Is this a constraint due to the CNC mechanism? Must the parts printed in Trueshape adhere to CNC geometry constraints?

Finally, there doesn’t seem to be any publicly released images of the machine or it in operation on their website. While the company says they have supplied a number of parts to test customers, it would be more reassuring to see an actual machine. This could be because they don’t wish competitors to see how the machine works.

Nevertheless, it seems that Mantle is now another low-cost metal 3D printing option.

Via Mantle