After our story about electroplating last week, we were contacted by RePliForm.

RePliForm is a Baltimore-based company that provides metal plastic composite services. In other words, electroplating. While our previous story explained how one could undertake electroplating as an individual, RePliForm does it as a business.

The idea is clear: coat a “weak” plastic part with a metal surface to gain many advantages. Not other does the part become stronger, but it also gains forms of chemical resistance.

RePliForm’s President, Sean Wise, sent us a recent presentation entitled, “Electroplating on 3D Printed Plastics: An Unexpected Way to Make a Reinforced Composite and Add Metal Functionality to Non-Conductive Materials”. The presentation provided us with insights on electroplating we had not considered.

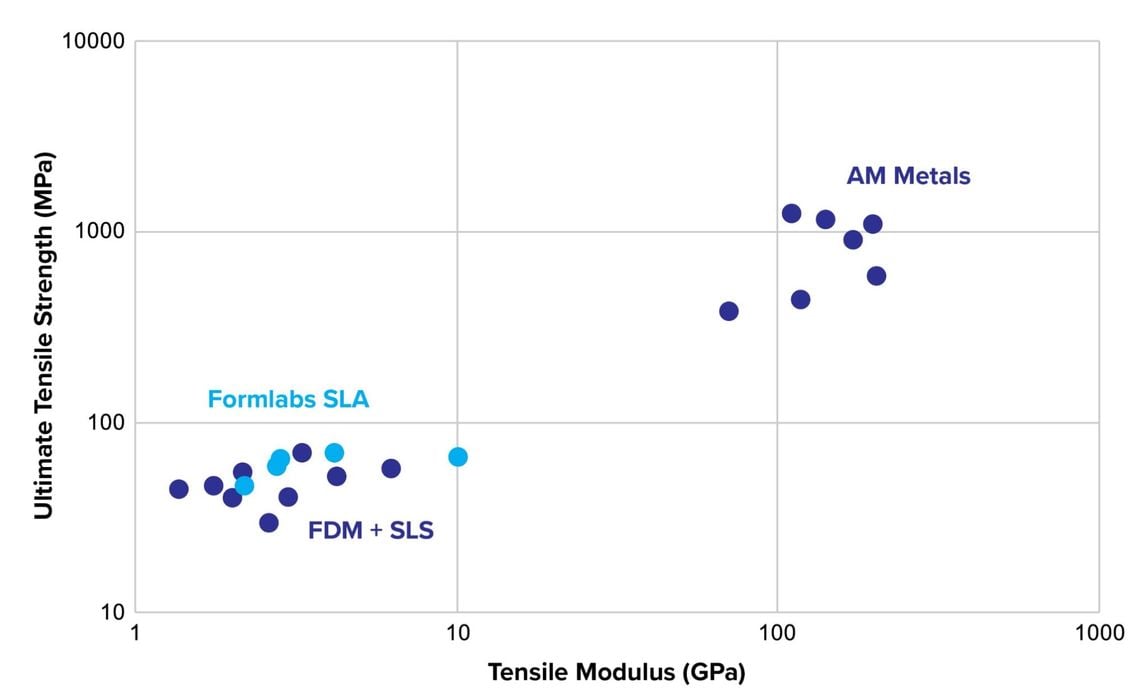

The main issue is this:

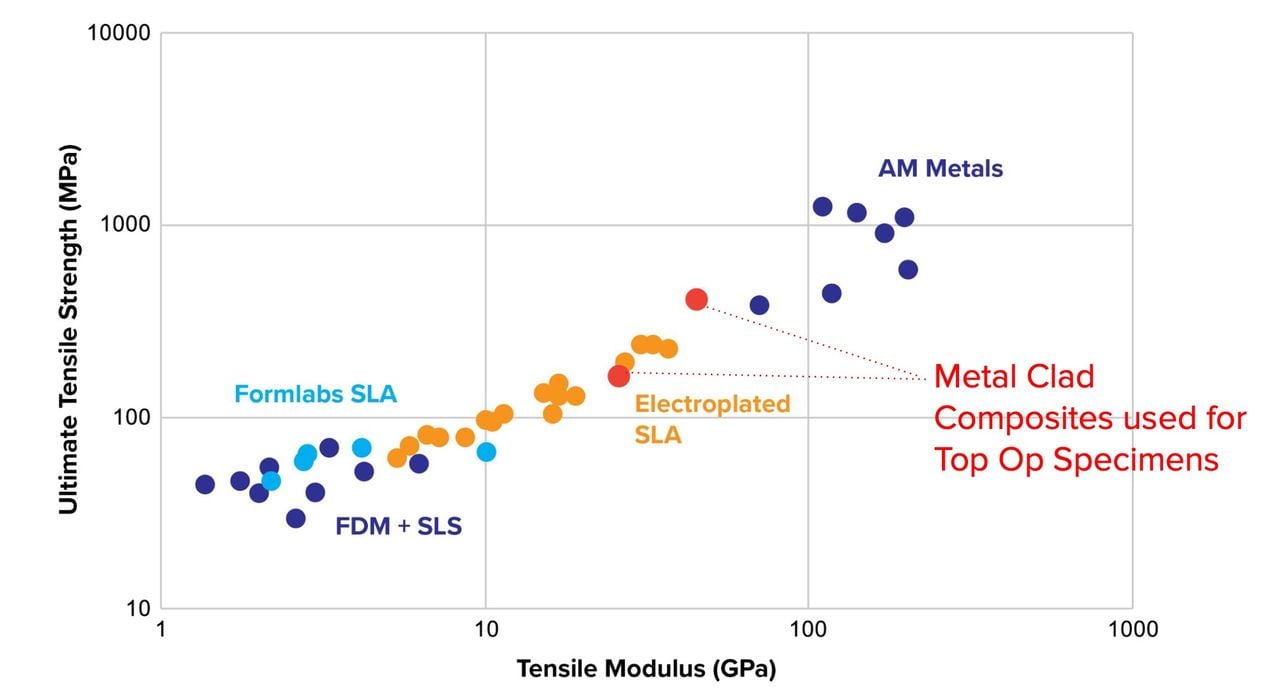

There is a huge gap in strength between polymer and metal additive parts. However, there is also a massive price jump to metal.

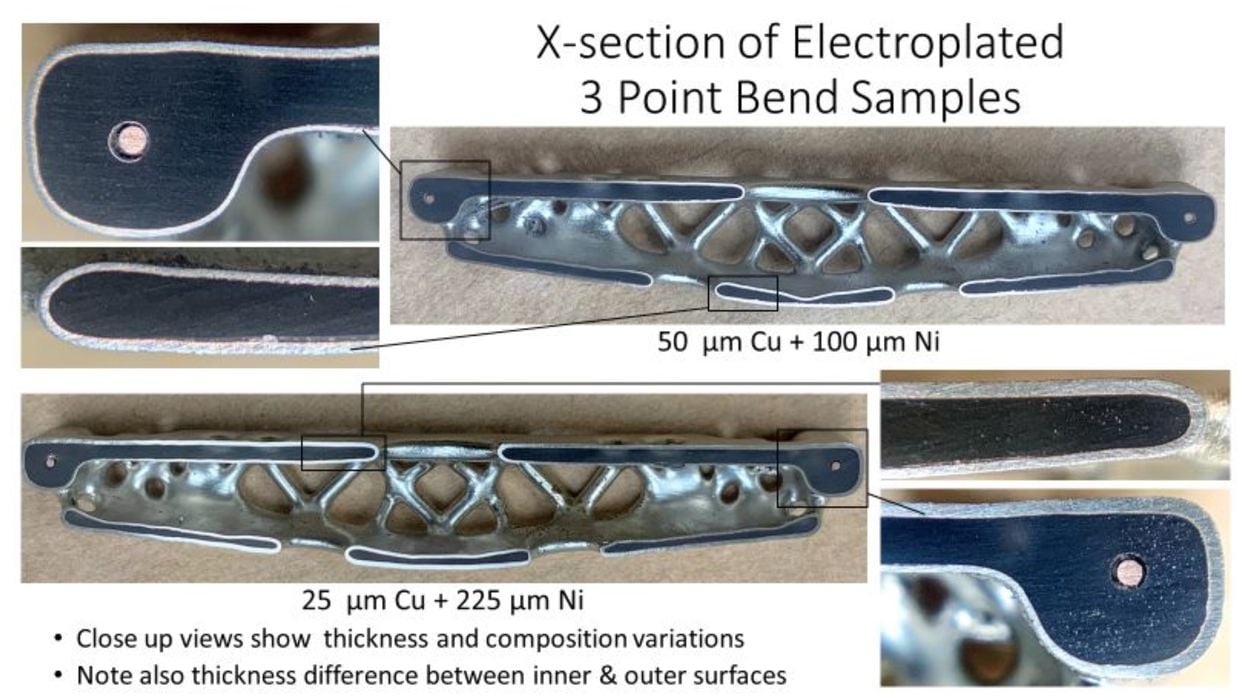

But there’s more to the story than just strength. The presentation explained that when electroplating parts, one must account for the thickness of the coating. This means that the 3D printed part must be printed slightly smaller than originally intended. This is a precision maneuver that must be carefully planned.

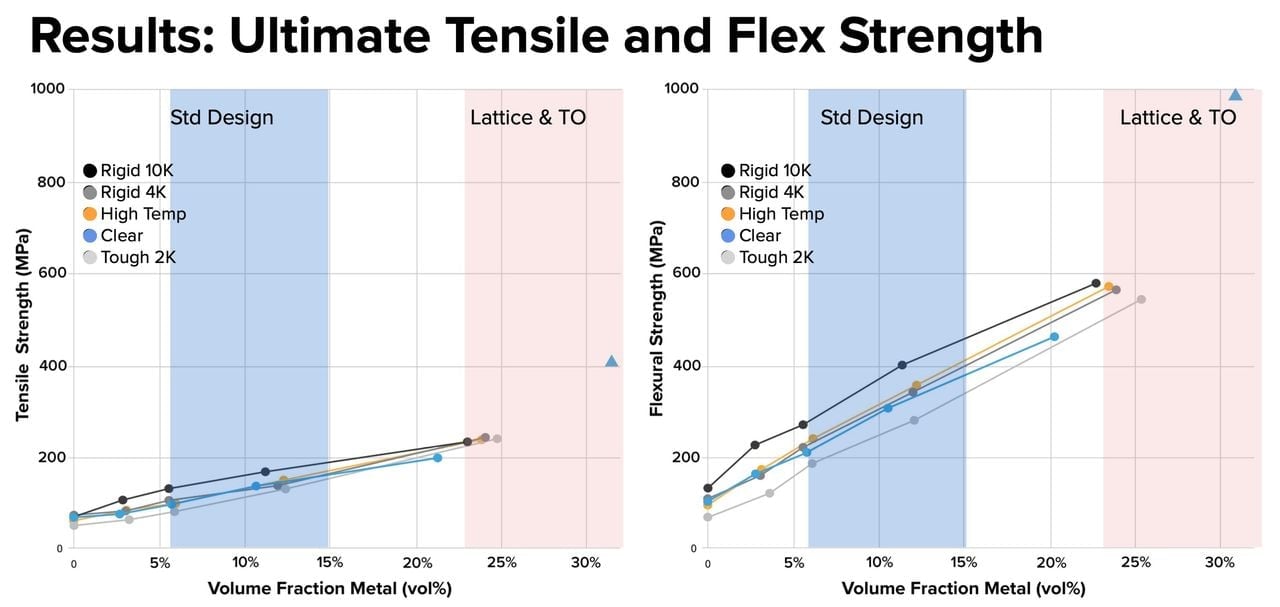

The presentation also pointed out that different 3D printed materials gain different strengths when electroplated. It’s not as straightforward as “this metal gives you this property”, because the underlying material matters as well.

What does this get you? This chart shows how the electroplated part samples land:

Indeed, it is apparently possible to get polymer parts a lot closer to pure metal parts using electroplating.

RePliForm explained that there are “good candidates” for electroplating, which include parts with:

- Open Structures

- Large radii between ligaments, nodes and

- surfaces

- Parts are loaded in bending/buckling

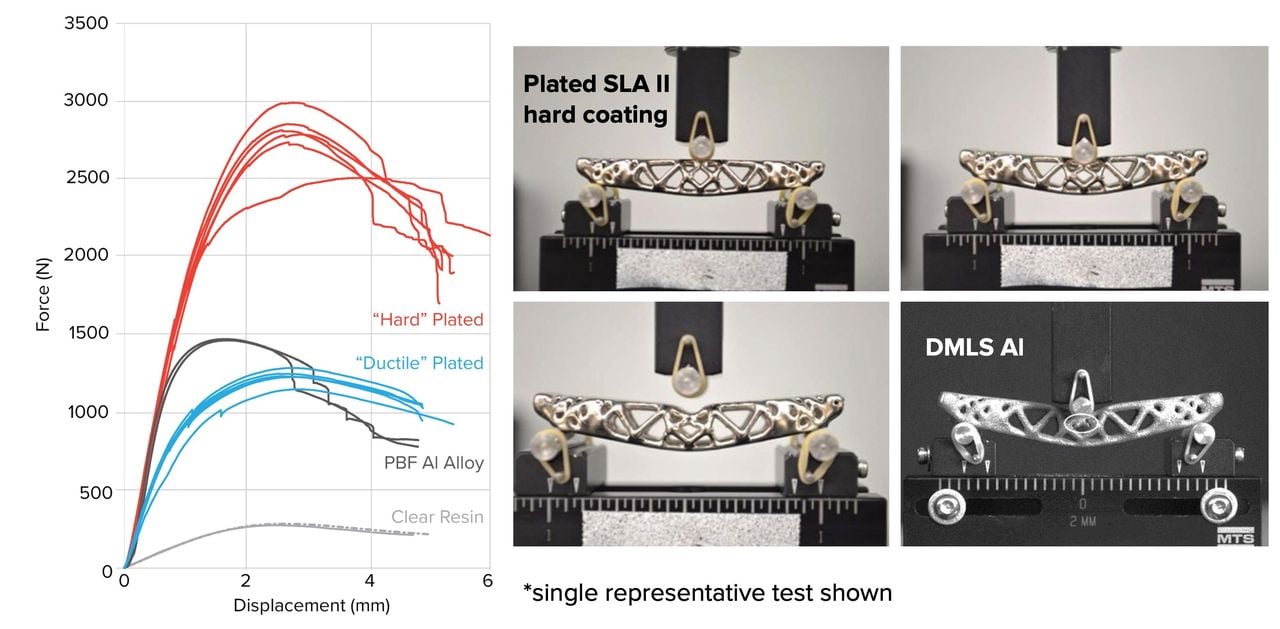

They also showed load deflection test results, showing significant force improvements on polymer resin 3D printed parts.

But is the cost less than just printing these parts in metal? The presentation explored this by examining the cost of a specific part in different quantities, both electroplated and printed:

The results showed the electroplate parts were one-third to one-half the price of metal equivalents, which is significant.

The implication is that if the mechanical force requirements of a part could be met with an electroplated version, it might be far less expensive to simply electroplate than print in solid metal. However, there are other concerns, such as thermal resistance that must be also considered.

The presentation included countless engineering measurements of different electroplating scenarios, all showing much the same thing: electroplated parts are almost as good as metal in many cases. They also showed a wide variety of applications, including EMI shielding, tooling, wind tunnel testing, spaceflight applications, antennas, and many more.

After reading this presentation, it’s clear that electroplating is a process that should be used much more by the industry. Perhaps RePliForm should be a service provider for your parts?

Via RePliForm