More research on foam-based structural 3D printing shows a way to significantly reduce CO2 emissions.

Construction 3D printers are just getting started. These huge 3D printers, either gantry or robotic, typically involve a concrete extruder. The motion system moves the printhead in a way to deposit the specialized concrete in the desired geometry.

While this system works, it still uses cement, which turns out to be a huge negative when it comes to the environment. While the construction 3D printers themselves do not emit a terrific amount of CO2, the production of cement does due to the heat required in the production process. In fact, cement production is one of the leading sources of atmospheric CO2.

The researchers felt that a non-cement-based material might be better for construction 3D printing, and they focused on the foam concept.

This is quite intriguing, because foam is a natural insulator. If a structure were 3D printed with foam walls, it would automatically be insulated. This would in turn reduce the need for heating and cooling throughout the seasons, also contributing to CO2 reduction.

However, there are two kinds of foam at play: one type is polymer-based, such as polyurethane. The researchers wanted to avoid this type because it implies use of fossil sources.

Instead they focus on non-organic foams made from other materials, which they describe as “cement-free geopolymer hardened material”.

In practice, this means they are using a mix of fly ash, water, retarders, “mineral additives”, and a hardener. The retarders keep the slurry “wet” as it sits in a reservoir waiting for printing. The hardener is mixed in at the last moment and triggers the solidification.

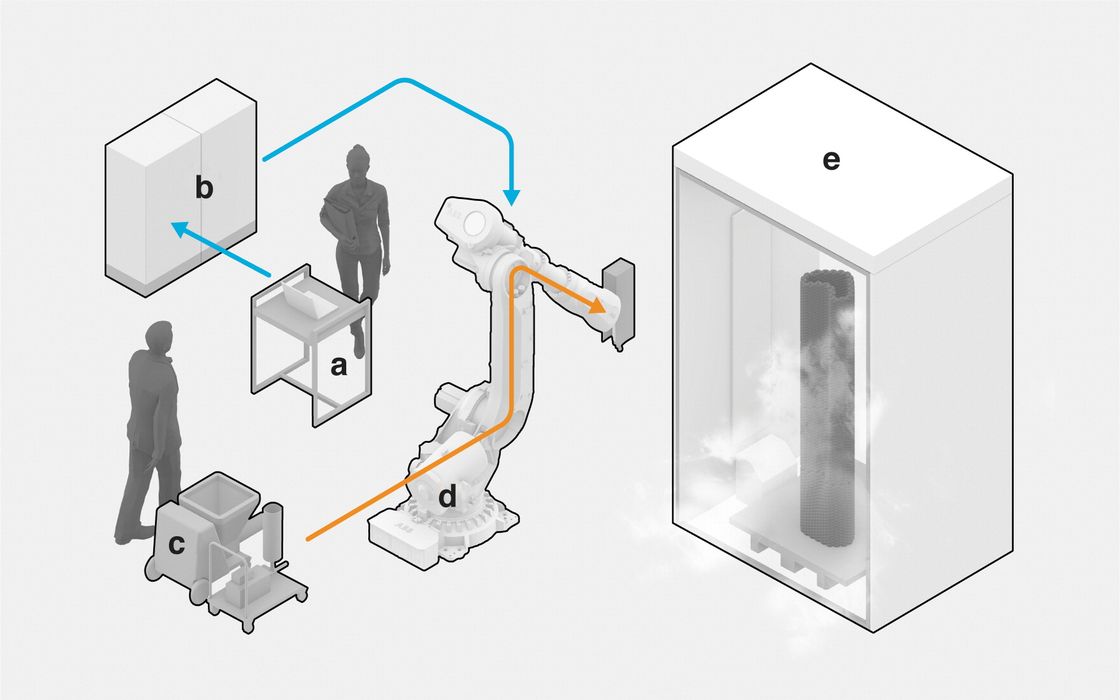

Their experiment, shown at top, involved a robotic deposition approach. They used a standard 150kg ABB robotic arm, but equipped with a specialized print head for the experiment.

The print head acts as the mixing chamber for the base slurry, hardener and air. It seems that there is a rotational element that very rapidly mixes these components and at the same time generates the foam. The rotation is so extreme that cooling is required.

After that, the robotic arm then deposits the foam material in the desired geometry, which quickly solidifies.

Their experiment involved 3D printing several large building sections that could be added to a build project. However, I believe the intention here is to 3D print an entire structure, which may be the next step after this proof of concept.

The proof of concept was essentially determining the print parameters for successful deposition. They had to play with the retarder dosage, mixing RPM, deposition rates and much more. Testing involved the classic concrete slump test.

Eventually they were able to successfully 3D print foam structures using inorganic foam material, in a process they call “F3DP”, for Foam 3D Printing.

This work looks incredibly promising, and I am hoping they will continue the research, and ultimately commercialize the process.

Via Liebert