With the increasing number of belt printer initiatives appearing, I’m wondering how they will handle different materials.

3D Printing Different Materials

It’s a question of making adaptations to a 3D printer to accommodate the peculiarities of a given material. For example, some changes might be:

- Change to an all-metal hot end to allow use of higher-temperature materials

- Use direct drive extrusion to handle challenging flexible materials

- Increase fan ducting to help freeze materials more quickly

And so on.

Adhesion In 3D Printing

But the number one change done to 3D printers to accommodate different materials is to make changes to the build surface to allow for proper adhesion.

Adhesion is perhaps the most important aspect of FFF 3D printing: if the print doesn’t stick to the bed, it will certainly fail. Because of this 3D printer manufacturers have spent considerable time developing solutions.

At first the ‘solutions’ were rudimentary approaches like applying a layer of painter’s tape to the bed, or using obscure brands of hairspray. Then, things got more sophisticated. We saw the introduction of purpose-designed surface treatments that could be applied to rigid print surfaces.

But perhaps the pinnacle of adhesion design came with the now-should-be-standard approach of using a flexible spring steel plate with adhesive coating. I’ve found this approach to be the most reliable and easy to use among all solutions.

But there’s a bit of a problem.

These surfaces and treatments are only useful for specific sets of materials. For example, a surface might be terrific for use with PLA, PETG and even ABS materials, but be terrible for nylons. Similarly, manufacturers of surface treatments have diversified their lines to account for the varying chemistry of different 3D print materials.

For example, a look at Magigoo’s product line now shows:

- Original

- Pro Metal

- Pro PC

- Pro PA (Nylon)

- Pro PP

- Pro PPGF

- Pro Flex

- Pro HT

All of these are slightly different mixtures that are optimized for adhering the named materials.

Steel sheet vendors have also reacted to this situation. BuildTak now sells adhesion sheets specifically for nylons and flexible materials along with their original PEI solution. Curiously, they also offer “Rapid Tac Applicator Spray” for larger-sized prints.

In a way all this adhesion specialization is a reaction to the overall diversification of 3D print materials. The days of only PLA and ABS are long, long gone, and today it’s common to find many people 3D printing in nylon, carbon-fiber, PETC, PC and other previously exotic materials.

Belt 3D Printer Adhesion

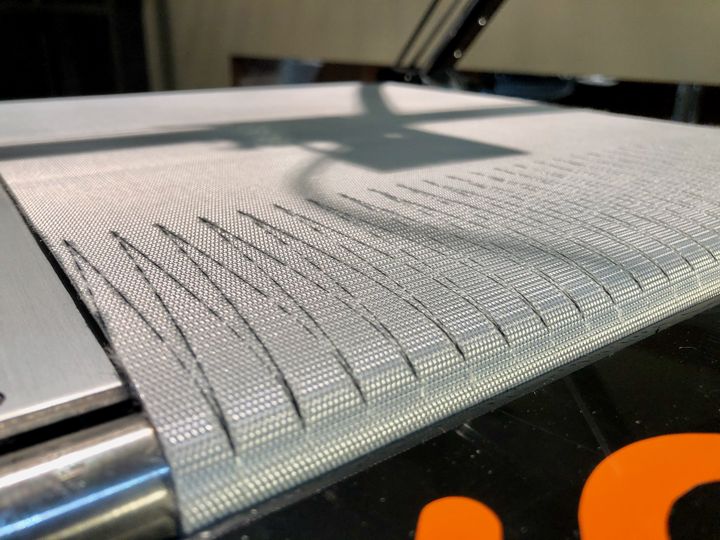

Back to belt 3D printers. These are unusual 3D printers that employ a conveyor belt instead of a fixed build plate that is found on all other FFF 3D printers. The idea is that the device can 3D print continuously as the conveyor belt moves, and this also allows printing of very long objects. It’s a fascinating concept that I believe will eventually become a standard approach.

However, the world into which belt 3D printers emerges is most definitely not one of PLA and ABS. Today there are multiple materials in almost every 3D printing workshop. Filament vendors sell dozens of material types, and for some it’s a routine operation to stop and consider what form of adhesion should be used for a given 3D print job.

My question is this: How do you do this on a belt 3D printer?

The conveyor belts that come with today’s belt 3D printers are designed to handle the basic materials such as PLA, ABS, and PETG, and perhaps a few others. However, chemistry dictates that it is unlikely that a single belt could be obtained to properly adhere ALL 3D print materials.

So what does one do? Swap out the belt for an alternate that’s designed for the new material? This would be easily done with a spring steel sheet system, but uncomfortably difficult for a belt 3D printer. Changing the main belt on a belt 3D printer is a non-trivial operation, at least in the way that belt 3D printers are designed these days.

Could a temporary treatment be applied to the belt to hold down a specific material? I suppose that could be attempted, but there are a number of challenges:

- The belt is huge and it would require a lot of material to cover all of it. Or, how do you identify which specific section needs the application?

- Belts are made from flexible materials that would likely soak up the treatment quickly and require far more than would be required on a flat rigid surface.

- Cleaning each application off the belt would be challenging, and might require removal of the belt anyway.

- An operator expecting to 3D print in different materials frequently might have to buy multiple belt 3D printers to accommodate surface adhesion.

I think you see the problem now.

Honestly, I can’t think of a good solution for this challenge, aside from having separate machines for different materials. That’s not optimal.

What do you think? How will belt 3D printer handle multiple material types in the future? Is there a solution involving chemistry that could apply here?

Is this really going to be a problem with the exception of the first line? Unlike cartesian printers that we know and love (or is that love to hate), the second row will have a bead of filament already on the roller to adhere to…