When recession pressed his engineering consulting firm to pivot, Tharwat Fouad dismissed the hype and did his homework.

Additive manufacturing has come a long way in the last 20 years, becoming a critical production method for manufacturers in many industrial and consumer sectors. That wasn’t always the case. There was a time when 3D printing was costly, complicated and unproven with few available materials and even fewer viable applications. But the potential upside was strong enough that companies looking for a competitive edge or a niche to call their own decided the rewards outweighed the risks.

This was the situation for Tharwat Fouad, president and founder of Anubis 3D Industrial Solutions. Anubis, a Canadian company located near Toronto, is a polymer 3D printing service provider that makes end-of-arm tooling for robotic applications and 3D prints prototype or low-volume industrial components.

Anubis wasn’t always an additive manufacturer. It got its start in 2006 as an engineering consulting firm that focused on fixed asset management. It was a good fit for Fouad, an engineer who had managed engineering projects at Procter and Gamble for 18 years—and the consulting work was steady—at least at first. But as the Great Recession took hold, the company stared down the barrel of an uncertain future. With contracts being cancelled and little new work in the pipeline, Fouad knew Anubis needed to transition to a more sustainable business.

“We had nine ideas we could work with and 3D printing was one of them,” says Fouad. “There was a future in it. We could merge the engineering knowledge we have with the new industry and technology [for] an advantage to enter the market, rather than being another CNC shop down the road. It was a technology that needed innovation, and we were not short on that.”

There was significant hype surrounding 3D printing as the next major disruptive technology, but Fouad did his best to ignore it. Knowing he had only one shot at his company’s pivot, he investigated the technology on his own before committing to 3D printing.

The first order of business was to design some simple parts to see what the technology could do. Fouad ordered these parts from different companies using different styles of 3D printing, then examined the results.

“Once you do that, it’s clear what the differences are between the technologies, and we had a couple of important observations. We were looking for a technology that could become a mainstream manufacturing process,” he says. “It was also clear that SLS is the process for mainstream because it was in the sweet spot between advanced technology and ready-to-use. It gave you predictability in shape, geometry, tolerance and physical properties, and is consistent in terms of mechanical properties.”

For Anubis, this predictability and being able to match or even exceed the expectations of the model was a key consideration. Although SLS had some downsides, it could produce predictable outcomes if its users understood its limitations and designed within them. Fouad also tested FDM and SLA-style printers, but decided those technologies were more suited to prototyping. He wanted to do repeatable, detailed work, and SLS was the answer.

The next step was to define the business model, with Fouad leaning towards becoming a 3D printing service bureau. Customers would design their parts and Anubis would print directly from those files. Unfortunately, the idea never took off.

“We went in [to potential customers] with our sales pitch ‘Look what you can do with 3D printing and here are some examples,’ and people were amazed, but nothing came out of it for almost two years,” Fouad recalls. “We couldn’t sell anything because people were still using additive as prototyping. Nobody had the trust to use it for more than that. They didn’t know if it would work and didn’t have the time to develop for it.”

Dejected but undeterred, Fouad made another pivot, this time as a problem solver. The plan was for customers to explain the cause of their problems to Anubis, which would use its design expertise to develop and print a solution. This approach gained traction, but not in the way Fouad expected.

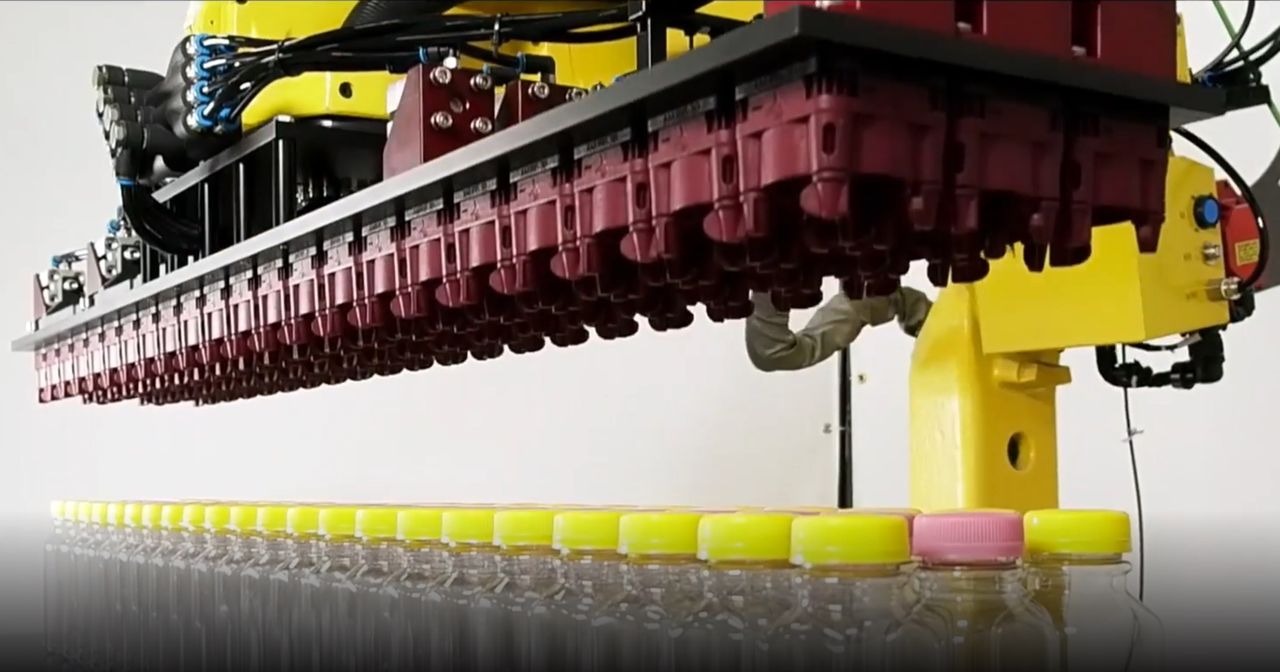

“The only parts that [customers] were always coming back to us for was the end-of-arm tooling (EOAT), because they needed lightweight tools that worked in very limited space,” says Fouad. “They faced lots of constraints around the design and making it out of metal was not working.”

Anubis’ customers were mainly robot and automation integrators—the companies that combine robots with conveyors and other equipment to automate production lines. In the past these integrators would tackle material handling problems with simple mechanical solutions or make their own EOAT which generally consisted of a metal plate and some suction cups. As robotic technology became more complex, so did the tasks these robots were performing. They needed more speed and accuracy than the mechanical solutions could achieve and the metal EOAT was too heavy and clumsy to get the job done.

“That’s how we ended up focusing on tooling. The customers we worked with in the beginning started trusting the product. For new projects, they began to see us as a first option, not as a backup. And this is where we started developing ourselves as a toolmaker using 3D printing,” says Fouad, who admits that the first few years were very tough. “It required a lot of investment, but we came out of it becoming experts in how to build end of arm tooling as a standard product using 3D printing. We didn’t have any competitors because nobody else was crazy enough to do what we did.”

Read the rest of this story at ENGINEERING.com