How complex is reverse engineering, and is it a major activity?

I saw an interesting question posed by Andrew Sink on Twitter:

“The biggest opportunity in the 3D/AM field right now is a simplified mesh-to-CAD tool; someone is going to make a lot of money solving this problem.”

I considered this question and have some thoughts.

First, I don’t think Mesh-to-CAD is the biggest opportunity in the space right now. Instead that’s likely to be wide-scale manufacturing, where there is said to be US$12T spent today. If even fractions of that were spent on 3D printing tech, it would be a massive opportunity.

What is “Mesh-to-CAD”, anyway?

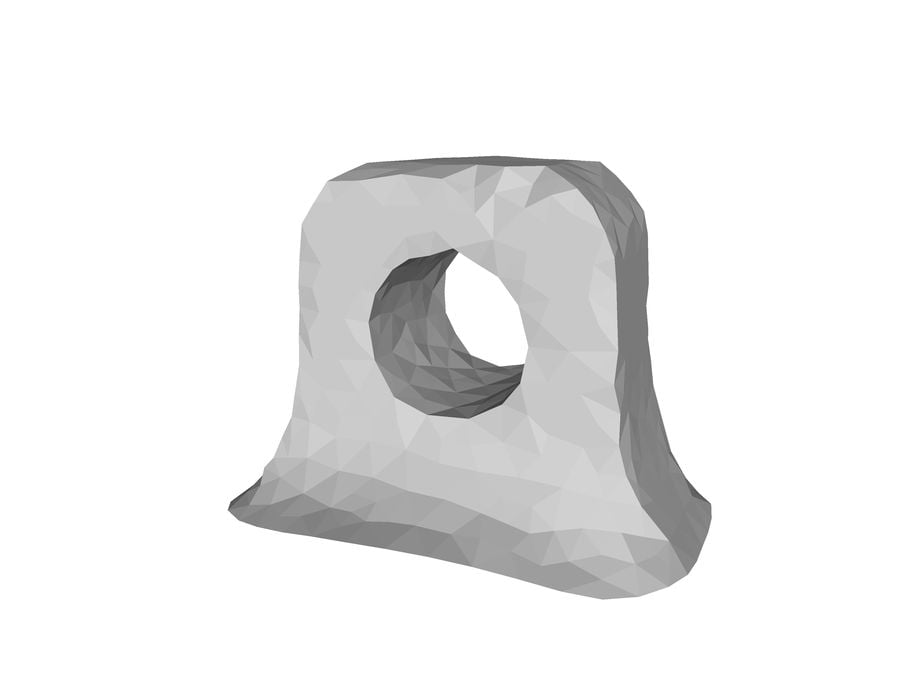

This is the process of transforming a mesh, such as an STL file, from a series of triangles representing the exterior “skin” of the 3D model, into CAD form. A CAD file is a sequenced series of 3D operations on basic primitives to form a sophisticated 3D representation.

The two formats are utterly different, but attempt to digitally represent the same object. Where STL is the “plastic bag around a loaf of bread”, the CAD file is the bread inside the bag, and the bag.

Mesh-to-CAD is frequently a key step in reverse engineering. This occurs when a part must be reproduced, yet there is no 3D model for the part.

The usual sequence of events is:

- 3D scan the existing physical part to obtain a rough digital representation (a mesh)

- Use the scan as a guide to rebuild a new CAD model that matches the part

- Throw away the scan

- Export a new, fresh and clean mesh from the new CAD model

There’s only four steps here, but the big one is the rebuild stage. That is often done manually, as it requires a person to intelligently identify structures and primitives within the scan to use in the CAD model. The process is akin to 2D paper tracing, except that you’re doing it in 3D.

There are some CAD tools that specialize in reverse engineering. Do they do the job automatically? No, they don’t, but they do offer a variety of assistive functions to make the process somewhat less painful. The tools might recognize a flat surface here, a curve there, and speed up the operator’s work slightly.

If that’s what the process is, could it be a big opportunity?

Ultimately it depends on how many parts exist without corresponding CAD files — and of these, how many will actually be required.

In many cases designers simply create new parts and ignore the old parts and reverse engineering process entirely, thus not requiring a specialized Mesh-to-CAD tool.

Could it be possible to build a fully automated Mesh-to-CAD system? I think it would be extremely challenging.

While it may be possible for a machine learning system to “recognize” structures within a 3D scan and flip them to corresponding CAD elements, it’s highly likely this would be restricted to categories of objects.

For example, I could see a system being able to recognize “bolts” and crank out the corresponding CAD file. But then if you need “nuts”, you’re looking at a completely different recognition system.

The problem gets more complex if you want a universal system that can recognize ANY object and produce a CAD file. How many objects could there possibly be?

Many.

And that’s a bigger challenge than any machine learning system could attempt, at least as of now.

Back to the original question: is automated Mesh-to-CAD a big opportunity? While there is likely to be some demand for it, I can’t see it being the biggest opportunity. And I can’t see fully automated solution being developed any time soon.