A unique research project hopes to 3D print critical chemicals at risk of extinction.

The research, undertaken at the University of Rochester, attempts to provide a solution to a problem that may face the world in coming years. As the climate emergency continues, there will be ongoing extinctions in the biological world.

These extinctions could eliminate the source of certain important chemicals that are produced or derived from those organisms. Should they become extinct, our supply of those chemicals could be lost forever. There are a vast number of plant-derived drugs that could be affected by this change.

The researchers believed they could produce a 3D printing apparatus that could produce these chemicals synthetically, without the need for the original organisms.

The device they created was an entry into IGEM, the International Genetic Engineering Machine event, where researchers develop machines that can perform various genetic engineering tasks.

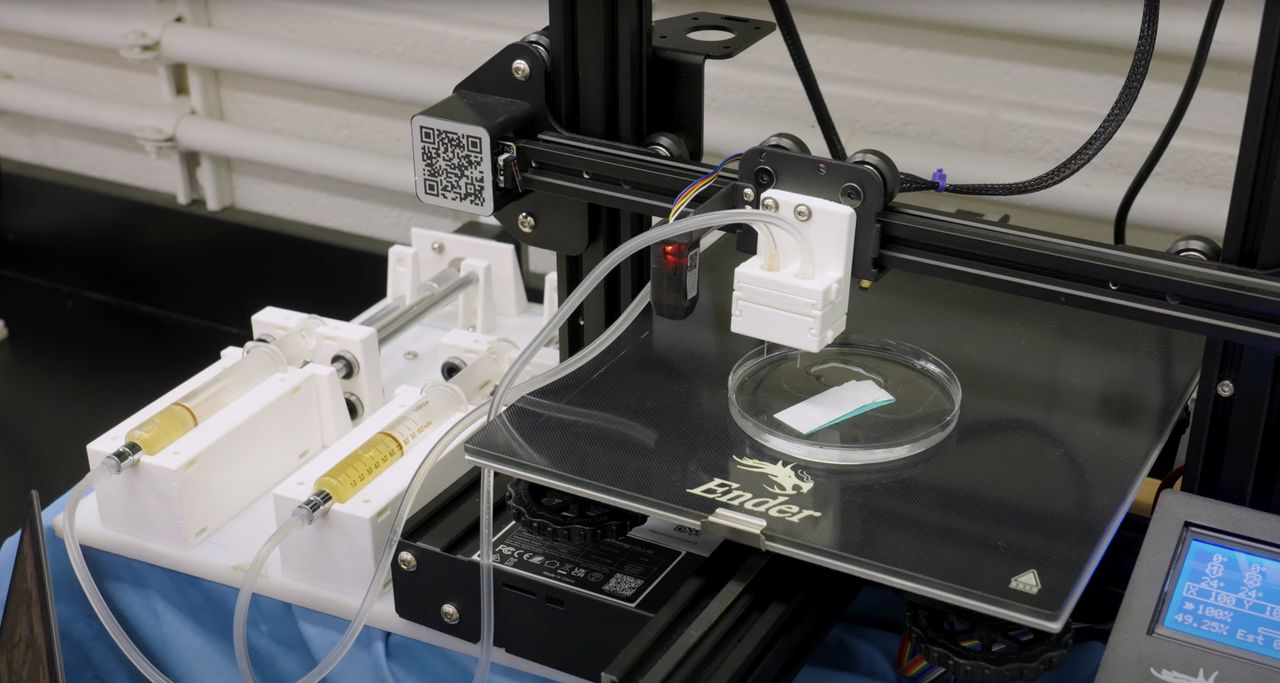

The team’s approach for this specialized bioprinter was to modify a stock Creality Ender-3 desktop 3D printer to become a bioprinter. This involved swapping out the normal FFF toolhead for a syringe-powered toolhead that could deliver bio material.

But what was that material? It’s actually a combination of two different materials. One is a yeast mix that is used as a food source for the other material, which is a solution of e.coli bacteria. The trick here is that the bacteria, one that’s commonly used by researchers, was genetically modified to produce a specific required chemical.

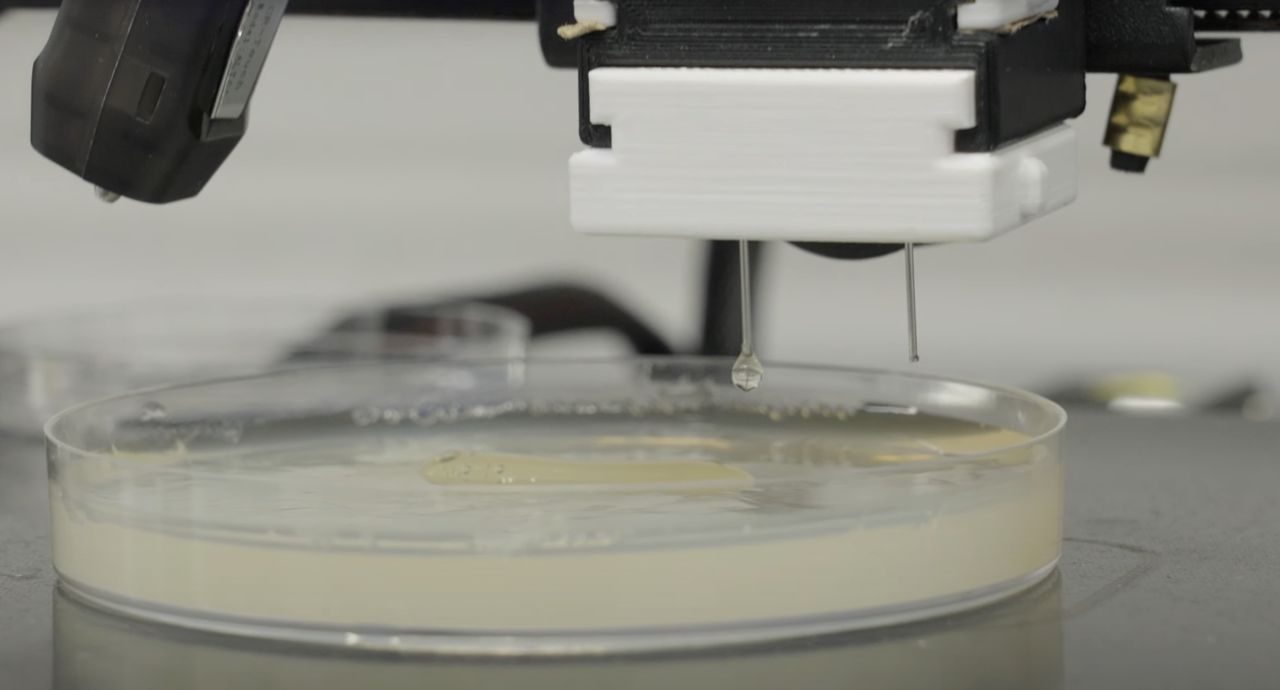

The print jobs would deposit bacteria and yeast in a pattern that encouraged growth — and production of the desired chemical. The resulting print is then left to generate chemicals as required.

If you think this is straightforward, it basically is: the magic is in the genetic engineering, which is done separately. The 3D printing phase simply packages up the materials in such a way as to easily and cheaply produce required chemicals.

The researchers say this approach can be used to produce almost any required chemical produced by biological sources. All it requires is to tweak the genes of the e.coli to include the instructions to produce the chemical.

The real breakthrough here is that the cost of their device is around US$500, which is vastly less expensive than typical bioprinters, which can range from US$5,000 and up. This opens up the possibility of using large farms of these bioprinters to produce chemicals at scale.

Should the climate emergency continue and mass extinctions continue, we may very well be glad this approach has been proven to work.