An interesting application of several 3D technologies took place in London recently.

The problem was found on the Tower Hill Memorial, a dedicated stone structure to remember casualties of the First and Second World Wars. This monument is located across the street from the Tower of London in Trinity Square Gardens, a place I’ve been many times. In one of my pictures taken from the gardens you can see the memorial in the background on the right:

The memorial includes the usual inscriptions, but also the names of the casualties who have no known grave. Unfortunately, historians have identified that some of the names were misspelled in 1928 and 1955, and still exist on the structure. Evidently back then some folks were anxious to join the war and signed up with false identities to avoid age restrictions and other matters, in addition to general administrative mistakes. Thus several of the names were incorrect.

The goal was to replace them in such a way as to ensure the look of the memorial did not change.

The project was undertaken by Gala Creations, a London-based 3D jewelry design, scanning and printing firm. While the replacement lettering on the memorial was definitely not jewelry, the technologies used by Gala Creations were definitely applicable to this unusual project.

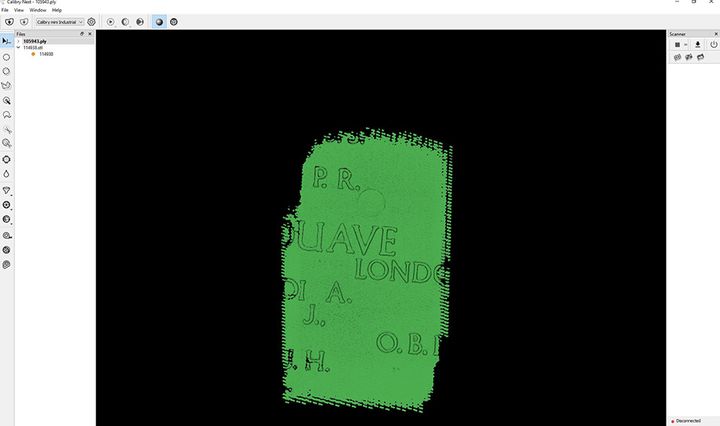

The Gala Creations team decided to 3D scan the original letters to understand their size, fonts and other characteristics. This was done using a Calibry Mini handheld 3D scanner.

Normally this particular scanner would be plugged into a wall electrical outlet, but I can say there aren’t any walls that I saw within Trinity Square Gardens. Instead, a generator was brought in to power the operation.

The letters were first sprayed with AAESUB Blue scanning spray, a substance that renders an object “dull” to avoid complications when 3D scanning overly shiny items. It fades away after several hours on its own, so no damage to the memorial occurred.

Samples of all four letter sizes were quickly captured with the equipment, and Gala Creations was then able to use MatrixGold software to prepare the 3D models. This is software normally used for jewelry design, likely why Gala Creations was familiar with it, but it can be used for general 3D activities such as this.

They created a point cloud and subsequently 3D models of the letters. In this application the team had to create “pin mounts” to hold the letters as well as the letter forms themselves.

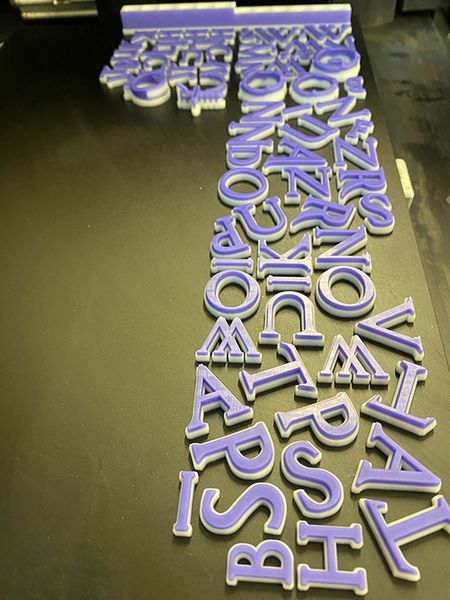

These 3D models were then 3D printed in wax, likely using jewelry 3D printers. The wax models could then be used in the lost-wax process to cast new letters in bronze. Nearly 200 bronze letters were produced, each of which underwent finishing by hand to ensure the letters had the same aged patina as the remaining letters.

Finally, the newly completed letters were mounted on the memorial where they remain today.

This is a great example of how 3D technology that’s normally used for other purposes can be re-used for an entirely different and unique project. Too often we set up our equipment and software for a specific use case, but fail to realize there are many more all around us.

Via Thor3D, Gala Creations and GoldMatrix