Charles R. Goulding reflects on “The Smart Mission” and what we can learn from studying successful organizations as well as private industry disruptors.

“The Smart Mission” is a new MIT press book described on the cover as NASA’s Lessons for Managing Knowledge People, and Projects.

The authors are Edward J. Hoffman, Matthew Kohut and Laurence Prusak. The book commences by delving right into project management and knowledge transfer. Hoffman was NASA’s first Chief Knowledge Officer, Kohut consulted for NASA on communications and Prusak consulted for NASA on strategy.

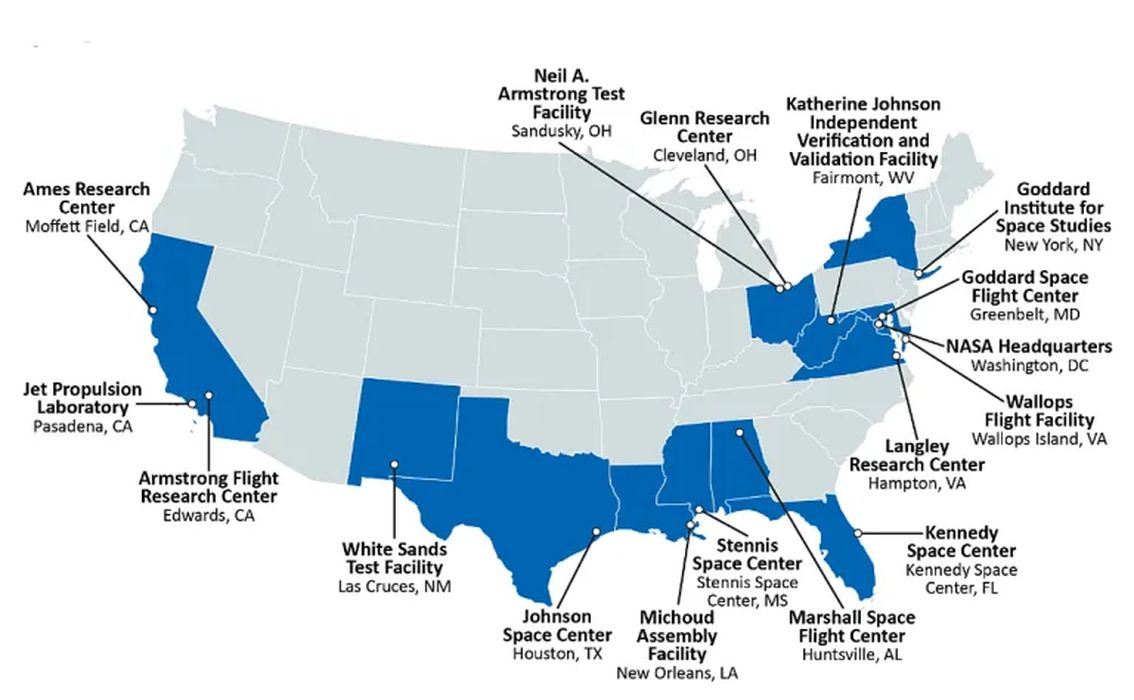

Although not included in the book it is helpful to understand the size and scope of NASA. Started by Dwight Eisenhower, NASA is a federal government agency responsible for space and aeronautics research. NASA has a broad interest in climate-related matters. It has a budget of approximately US$25 billion and approximately 18,000 employees.

The authors make it clear that NASA is scarred by the Challenger and Columbia tragedies. The space shuttle Challenger explosion occurred on January 28, 1986, killing all 7 crew members.

The Columbia space shuttle disaster occurred February 1, 2003, when it disintegrated re-entering the atmosphere again killing all seven astronauts on board. The author happened to be visiting IBM’s government division in Houston on January 28, 2003, and remembers the shocked reaction at this business unit that was a major contributor to the space shuttle project.

The authors refer to both incidents multiple times in the book and they resulted in a detailed review of NASA’s processes, procedures and culture. One example is the ability to speak up freely rather than be controlled by “command and control” culture.

I thought the book was particularly strong on how to transfer knowledge throughout an organization and ways to improve training. The authors feel that storytelling is a good way to transfer knowledge and that team interaction is a valuable part of formal training. They did a good job explaining the inadequacies of institutional libraries and training by PowerPoint.

Although they touched on the benefit of studying successful organizations like Google and Netflix, I would have liked to see some discussion of the current private disrupters like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and a plethora of other space startups.

Those disrupters have introduced game-changing technical improvements such as reusable rockets and integrating highly reliable consumer electronics components to reduce over-engineered solutions where high-performance products already exist in the marketplace.

The new disrupters make use of many 3D printing technologies which NASA is increasingly recognizing and supporting.

The Research & Development Tax Credit

The now permanent Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credit is available for companies developing new or improved products, processes and/or software.

3D printing can help boost a company’s R&D Tax Credits. Wages for technical employees creating, testing and revising 3D printed prototypes can be included as a percentage of eligible time spent for the R&D Tax Credit. Similarly, when used as a method of improving a process, time spent integrating 3D printing hardware and software counts as an eligible activity. Lastly, when used for modeling and preproduction, the costs of filaments consumed during the development process may also be recovered.

Whether it is used for creating and testing prototypes or for final production, 3D printing is a great indicator that R&D Credit eligible activities are taking place. Companies implementing this technology at any point should consider taking advantage of R&D Tax Credits.

Conclusion

There are valuable takeaways from this book. The Challenger and Columbia tragedies were terrible events that had to be studied and understood. Some activities like test pilots and Formula One drivers are inherently dangerous. The hope is we learn from the accidents and do everything possible to reduce future occurrences.