Sintratec has revealed more about their unusual CMF 3D printing process.

Sintratec is known for their SLS system: a laser sweeps across a flat bed of polymer powder, selectively fusing some particles together to form the desired geometry. SLS is a common process, and it is always used to produce polymer parts, typically in nylons.

Somehow they’ve adapted their SLS equipment to produce metal parts using a new process they call Cold Metal Fusion, or “CMF”.

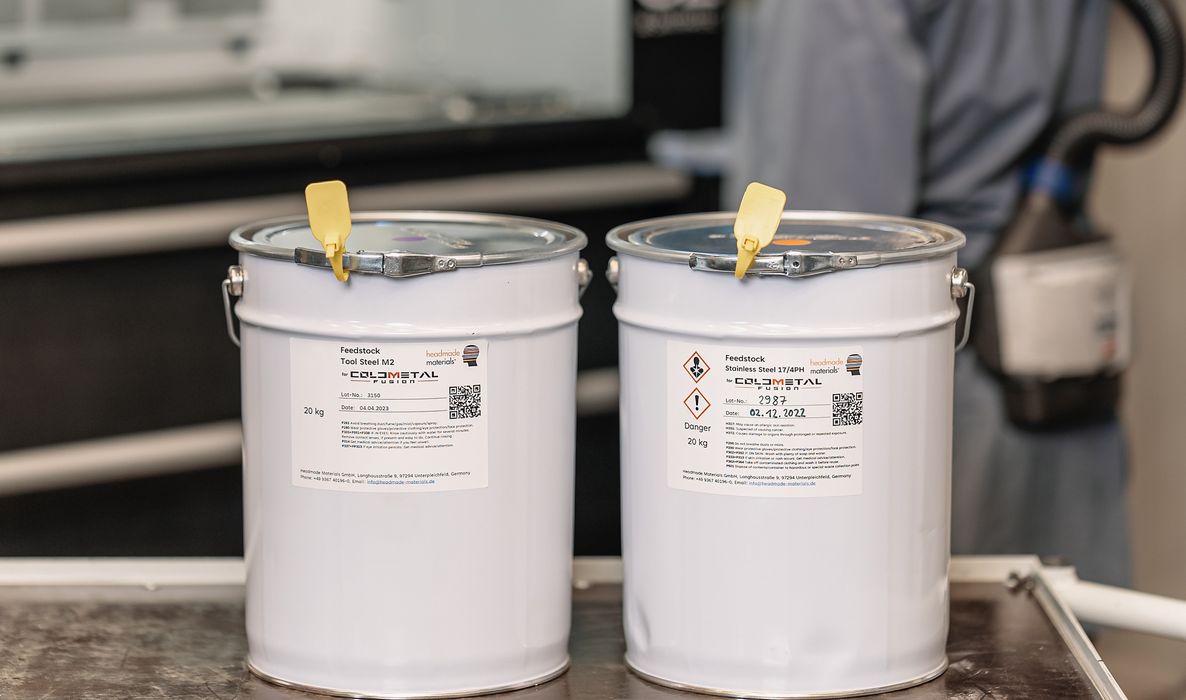

It turns out they’ve done something interesting with the material for CMF. Instead of using standard polymer powder, they instead use an “ingenious” powder of a polymer base with “metal spikes sticking out”.

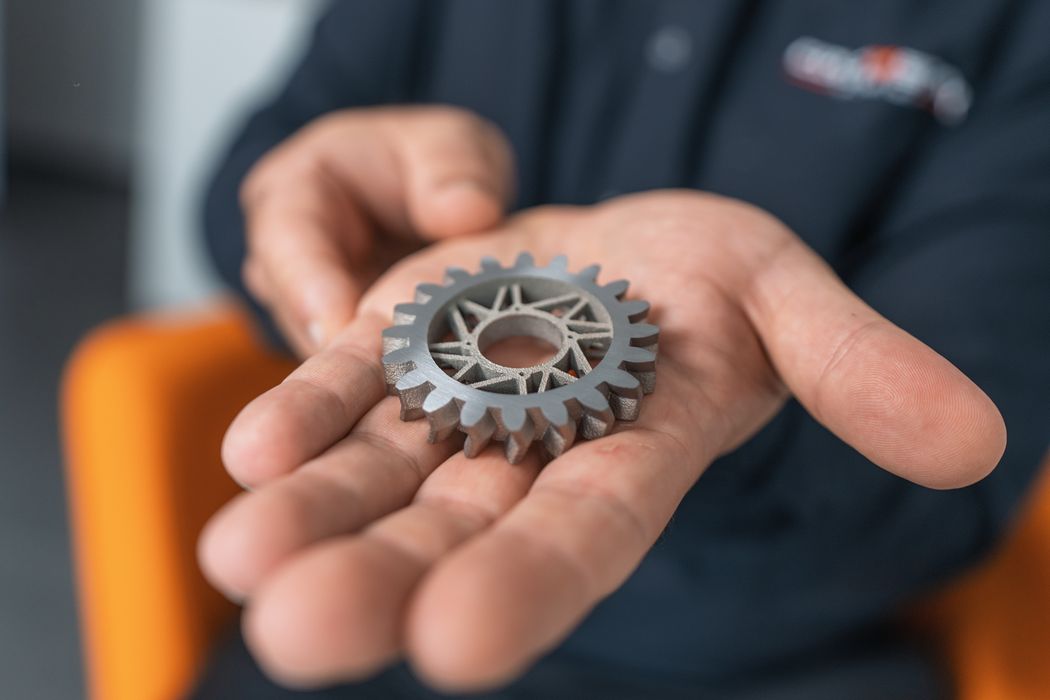

Now imagine this being fused by the laser: the polymer would melt, as usual, but the resulting solid structure would also contain lots of metal bits. Note that this is a “cold” process: the metal is NOT melted, only the polymer. Sintratec said the build chamber remains at about 50C during printing.

While SLS processing results in a more-or-less finished part, the CMF prints require significant post processing. The idea is to remove the polymer and sinter the metal bits together.

The first step is to depowder the print, which is almost always going to be coated with loose powder that wasn’t fused. This is where it gets interesting.

There are plenty of cold metal 3D print processes around, and they typically use simple binders to hold the metal powder together. This results in very fragile green parts that must be carefully handled during post processing.

On the other hand, Sintratec’s green CMF parts are quite solid because they are literally a polymer print at that point. This means you can rough handle them during depowdering operations. In fact, Sintratec recommends using their 30bar water jet system for blasting off powder. If you used that jet on typical binder jet green parts they would explode! This should make depowdering much faster, easier and less risky.

After depowdering, the green part is placed in a special chamber for exposure to acetone at higher temperatures for an overnight session. This chemically removes almost all of the polymer, leaving just the metal bits and a tiny bit of polymer.

The final step is to sinter the now “brown” part in a sintering oven. Sintratec said this step takes between 10-15 hours. After that the parts are considered complete and can be used for their intended purpose.

CMF is certainly an interesting metal printing process that offers some advantages over standard binder jet approaches. I’m thinking it could be of interest to SME’s seeking a simpler way to make small metal parts.

Via Sintratec