Small museums should consider 3D scanning their collections.

Over the past years we’ve heard a lot about major museums performing detailed 3D scanning operations on objects within their collections. The Smithsonian, in particular, has been quite deep into 3D scanning. They even offer some of these 3D models available for public download — and 3D printing.

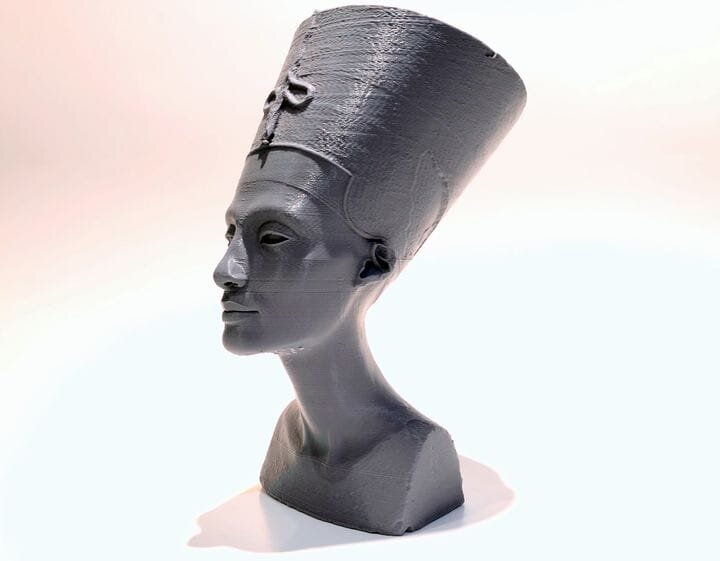

Other institutions are more secretive about their scanning activities. How do we know this? The infamous Nefertiti Hack of 2016 revealed that Berlin’s Neues Museum had been 3D scanning their collection due to a leaked 3D scan of their Nefertiti artifact from ancient Egypt. The scan was initially portrayed as an ingenious clandestine Kinect 3D operation by museum visitors, but was later revealed to be a preliminary 3D scan taken with professional equipment. The complete 3D scan is now available for anyone to use.

Then there was the fire in Brazil. In 2018, a massive fire broke out at Brazil’s national museum in Rio de Janeiro, with virtually all artifacts in the collection completely destroyed.

Evidently twenty million objects were lost in the fire, and unbelievable catastrophe.

Had that museum 3D scanned their collection, at least some information about the objects could have been retained for future generations, and replicas could be 3D printed. My understanding is that few, if any of them were scanned. A near-total loss.

After that event I am pretty sure that most major museums quietly began 3D scanning their collections, or at least discussing the possibility of doing so. Today, years later, there are no doubt some very comprehensive libraries of 3D scanned objects. Unfortunately most of them are not only not available to the public, but most likely some are entirely secret.

Along with the major museums of the world there are countless smaller local museums, all of which house unique objects related to the region on a wide variety of topics. These museum operations have similar or greater risks of fire and destruction, yet there is little mention of them undertaking 3D scanning operations.

It is quite possible to do so, however. As an example, I recently read of two museums in Northern Manitoba that recently undertook a digitization process.

The Heritage North Museum in Thompson, Manitoba and nearby Snow Lake mining museum both engaged Bit Space Development to 3D scan portions of their collections and develop virtual reality tours of their collections.

While not nearly as comprehensive as the scanning projects accomplished by major museums, this project was an important step towards digitizing that community’s heritage. Should disaster befall either of those museums, there’s at least some digital representations of the original content.

My hope is that more community and local museums begin digitizing their collections, as that is a way to help preserve them into the distant future.

The next time you’re visiting your own local museums, ask them about digitization, and help them find a way to do so.