I had a thought about the future of self-made 3D printer filaments.

I’ve been very skeptical of small filament-making machines for quite a few years. I witnessed absolutely terrible attempts at such equipment over ten years ago, with one infamous device literally spilling filament all over the floor, without even attempting to spool it up.

These rudimentary machines really didn’t work because the filament produced was of such low quality that it could not reliably be used to make quality prints.

Let’s poke deeper into that. Why does that occur? It’s because “quality” in filament generally refers to the consistency of the diameter. Quality measures are usually specified as the maximum diameter variance in a spool, these days something less than 0.05mm.

The GCODE that runs a 3D print job has no idea what diameter of filament is passing through the extruder at any moment, so it normally assumes that it is what was specified: 1.75mm, for example. However, in practice a poor quality filament would be wider and narrower at points. With the extruder running at a constant speed, this corresponds to blobs or gaps in a model as the variances are encountered.

Thus began a need for highly consistent 3D printer filaments. Filament manufacturers tuned their enormous filament production lines, adding meters and meters of precisely controlled water baths to meet specific thermal gradients during production. Sophisticated laser gauges were used to constantly measure the output filament, and sometimes even stored in databased by the spool.

Low quality filaments were forced off the market. Better prints resulted.

However, there were still attempts at making filament using small desktop machines. With one exception (3devo), I hadn’t seen any that would produce filament that was able to meet quality measures. This is totally understandable, since filament manufacturers use massive equipment to do so; how could a desktop machine even come close?

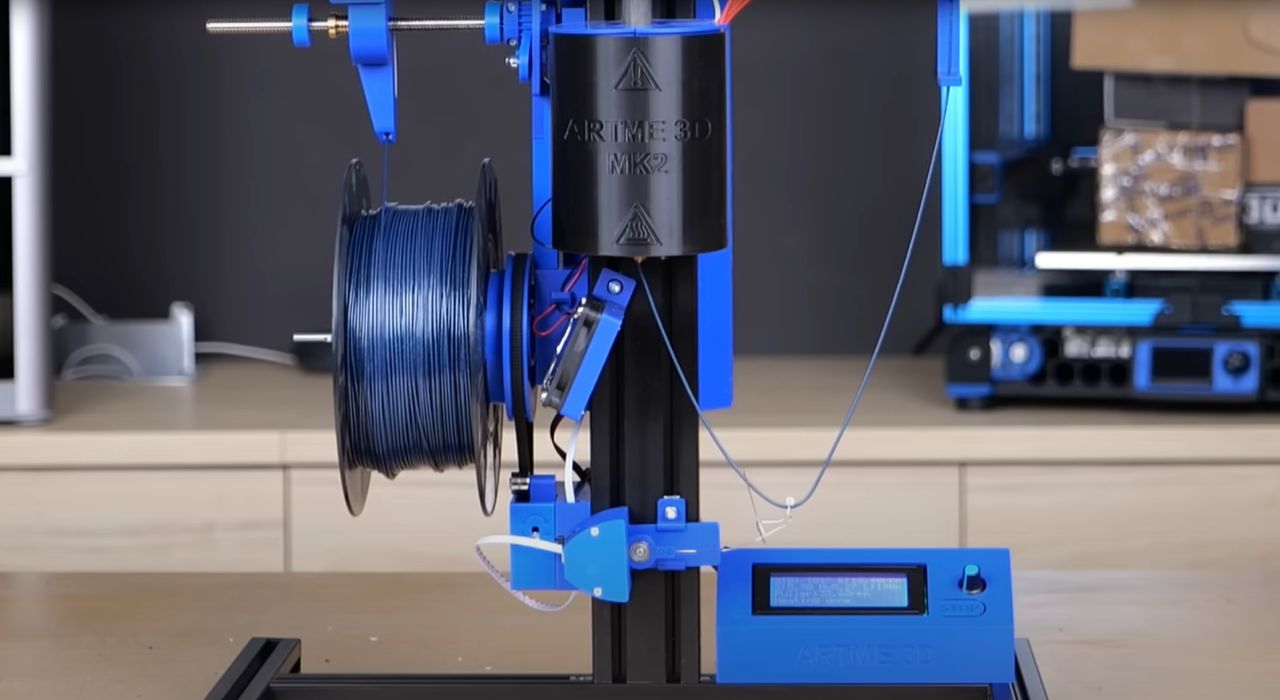

Then I saw a recent video from Stefan Hermann of CNC Kitchen, where he tested a new low cost filament device, the Artme3D. Hermann was able to successfully recycle 3D print scraps using several pieces of equipment, including the Artme3D, to produce usable filament.

Hermann found the filament quite good, or at least the prints came out with excellent quality.

Problem solved?

I think there’s a bit more to the story here.

Hermann’s testing in the video made use of the new Bambu Lab A1 mini, a device we recently reviewed.

The mini is a wonderful device with a ton of features and a very low cost. The prints that come off this machine are nearly perfect each and every time.

How do they achieve that? There are several reasons, but a key one is that the mini includes an “active flow rate compensation” feature. What does that mean? They explain:

“The A1 mini revolutionizes flow control in 3D printing. It utilizes a high-resolution, high-frequency eddy current sensor to measure the pressure in the nozzle. Our algorithm actively compensates the flow rate according to the readings to extrude with accuracy.”

In other words, if the machine determines the flow rate is too low, they tweak the speed to compensate, and vice versa.

Hold on, that’s exactly the problem that occurs with poor quality filament! This compensation allows the mini to extrude the proper amount of material regardless of variances in the input filament.

Let’s back up a moment: I have been skeptical of desktop filament machines because they generally cannot produce filament of suitable quality. But what if that NO LONGER MATTERED?

It would mean that desktop filament machines just might now be able to produce actually usable filament — if the 3D printer had proper flow rate compensation.

I’ve written several times on how Bambu Lab has disrupted the market: high reliability and quality challenged the professional market; features and capabilities challenged the desktop market; high speed capability has shaken up the materials market.

Now it may be that they are also going to disrupt the desktop filament recycling and production market.

Imagine a world where every desktop 3D printer has such compensation, and “crappy” filament can easily be used successfully. It would then be entirely possible to make equipment that would recycle print scraps into useable filament.

Which company could make such a machine? There are actually several projects that do so now, but all are not particularly consumer-friendly.

I do know of one company that is very good at transforming technical products into consumer-ready equivalents: Bambu Lab.

I would not be at all surprised now if that company announced a filament production machine.