New research at the University of New South Wales has shown a way to 3D print actual human bone.

Bone is a highly complex human tissue, as it is both strong and lightweight, mostly due to the detailed natural lattice structure on the interior. Most times a damaged bone can heal itself; a break needs to be set, and the body then re-joins the parts together.

However, the matter gets a bit more challenging when there is missing bone, and you can’t just simply paste two halves together and let nature take its course.

In those situations a bone graft is typically required. Bone material is “borrowed” from another less important part of the body and transplanted into the affected area. Since this bone graft is sourced from the same individual, it is almost always accepted.

The other approach is to build an artificial bone segment and implant that into the affected area. However, there’s many problems with this method, mainly because these artificial bones are almost always rejected by the body as foreign material.

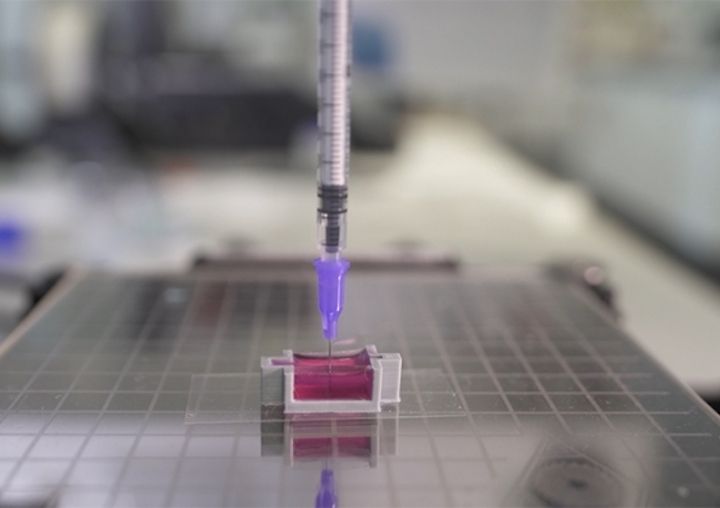

The new process involves 3D printing, and human tissue. Here’s how it works.

The target area is 3D scanned to understand the desired geometry of the artificial bone. The patient donates some living cells, which are cultured separately in a bioreactor.

The supply of replicated cells is then used in a bioprinter that’s inserting cells and “ink” into a gel mix. The ink in this case is a ceramic-based material that is made from hydroxyapatite, a type of calcium phosphate.

The idea is to use the ceramic segments as a guide for the natural human cells to build bone structures. This can then be implanted into the patient where the cells continue to build the bone back to a natural state.

The ability to 3D scan the target zone allowed the researchers to prepare new bone segments that fit very tightly, leading to better and stronger bone outcomes.

The bone segments could be prepared quite quickly, as the hydroxyapatite becomes solid near-instantly, and so in theory the print could be implanted rapidly, and bone growth could continue from within the body.

While this sounds quite promising, there are many steps yet to be accomplished. For one, the process has only been tested in small micro-environments, whereas it would have to be scaled up for many patients. This will require a few new developments, including a larger bioreactor and gel that can transmit nutrients to the cells and allow them to grow in a healthy manner.

The field of bioprinting is still very new, and there is so much yet to discover. This project is but one of many advances on that long journey.

Via UNSW