New research has shown a method to rapidly produce crystalline objects at the nano scale.

Researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Lab, University of California and the University of Birmingham have accidentally discovered an unusual microscopic process that takes place with nanoparticles.

Crystallization is a process everyone is familiar with; it’s the process that makes the ice in your drink, and the diamond in your ring. Molecules self-arrange into organized patterns that form solid objects.

Researchers have long been interested in finding ways to guide the growth of crystals so that they can be used to form useful structures made from useful materials. Unfortunately most materials don’t cooperate very well when asked to do so.

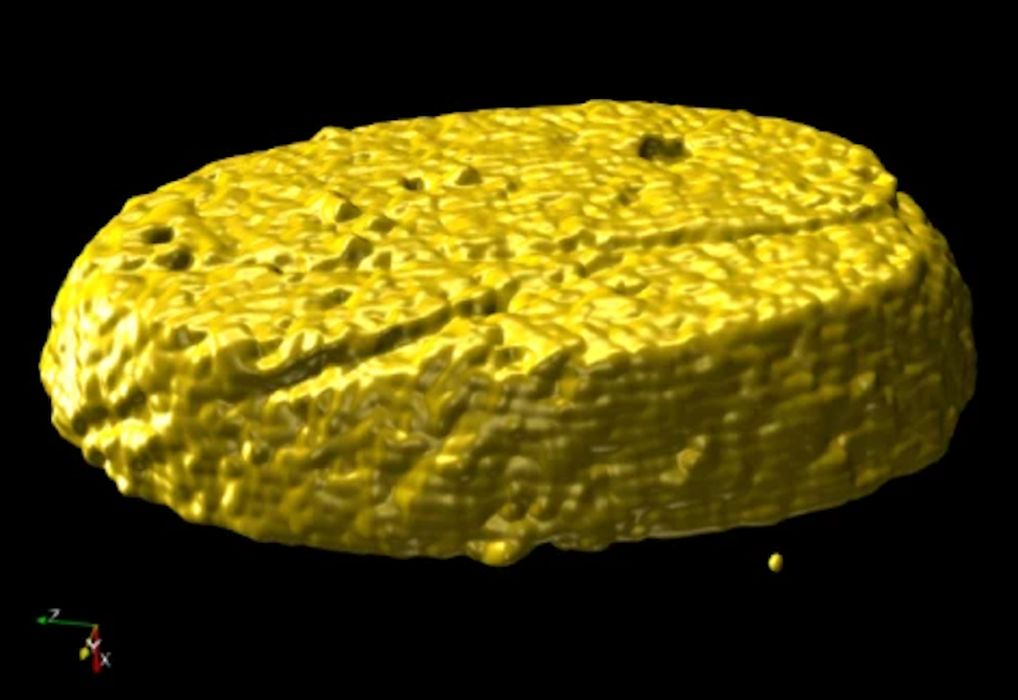

The ideal material for crystallization is nanoparticles, as they are sufficiently small and can be made from different substances. Previous research has shown methods of coordinating crystalline growth in nanoparticles using DNA molecules.

However, while that approach seems to work, it’s very slow. This makes it impractical to consider using the process to build anything but the tiniest objects.

The new research is all about speed.

The researchers were apparently looking at the DNA-nanoparticle process when they discovered the crystallization occurred far more rapidly than it should have.

An investigation revealed that the experiment had been polluted with a very small amount of polyolefins, such as polypropylene and polyethylene, likely from the experimental equipment.

Evidently the presence of the polymer caused the crystallization to very rapidly speed up. While the expected crystallization was in terms of days, the experiment achieved the same result in only minutes. Further research confirmed the addition of polymers to the mix did indeed speed up the process by an incredible amount.

The researchers are continuing to investigate this phenomenon, and are hoping to fine tune the process to enable the production of small specific-purpose structures, such as optical lenses. These would be “3D grown” rather than “3D printed”.

That got me thinking further about this process. What if it could be scaled to larger sizes? Would it be possible to build arbitrary objects using crystallization? These 3D grown objects would have tremendous strength, far greater than current 3D printing methods that typically have poor layer adhesion.

Certainly that vision is very far off in the future, but if researchers continue on their current path it is possible that could be achieved.