The folks at Proper Printing YouTube channel decided to combine FFF and SLA 3D printing processes, with interesting results.

FFF 3D printing is the most popular process these days because of its low cost, safe methods and good results. FFF involves heating a thermoplastic filament to “toothpaste” softness, and then depositing it in a pattern, layer by layer.

SLA 3D printing involves use of a photopolymer resin that solidifies when exposed to a sufficient amount of UV light, often by a laser. The laser traces “solid” paths through a surface of resin, creating objects layer by layer.

But could these two very different technologies be combined to form a unique “FRF” 3D printer? Jón Schone of Proper Printing decided to figure out how to do it.

And he did!

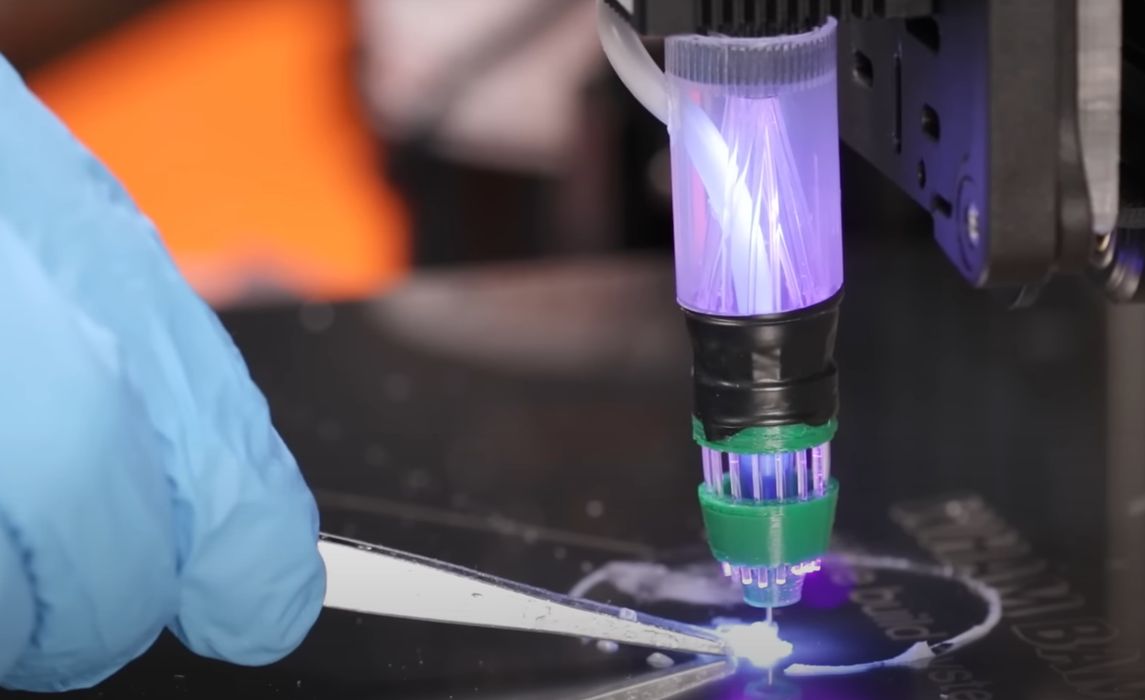

The idea was to replace the hot end of a FFF 3D printer with a syringe-like nozzle that would deliver photopolymer resin. The resin would be immediately solidified upon nozzle exit by a suitable laser aimed at the space just beyond the tip.

But how would the resin arrive at the nozzle? Schone designed a peristaltic pump — which was 3D printed, of course — that could deliver the resin to the nozzle. However, that type of pump pulses periodically and Schone had to figure out a way around that.

In the video below, Schone goes through the entire experimental experience of designing the Frankenstein “FRF” device. Because of his choice of using a laser instead of LED lights, there were safety concerns. Schone had to wear eye protection during the experiments, as well as using a fume extractor as is customary when working with toxic photopolymer resin.

After confirming that the basics of the concept were actually workable, Schone then redesigned the toolhead to hold the laser and nozzle. In order to deliver the UV light energy in a proper manner, the laser beam was split using glass fibers that were arranged in a circular pattern around the nozzle. This allowed UV light energy to hit the wet resin regardless of the direction of the toolhead. Also, the laser source itself was rather large and heavy and could not be mounted on the toolhead itself. This is similar to the situation found in laser cutters, where the beam is directed by mirrors to the target.

The experiment proceeds through quite a bit of tuning, as would be expected since this is an entirely new 3D printing process. One issue was that the resin was solidifying in the nozzle before it exited as UV light would leak in. This was fixed with opaque electrical tape, as you will see.

In the end, the initial concept didn’t work, but a redesign involving two side-mounted laser units seemed to do better, but still not quite successful. It seems there are plenty of issues to solve, and it sounds like this will be attempted in a future video from Schone.

Could the “FRF” concept become a commercial product? I’m not thinking it will for several reasons.

First, working with resin is not fun at all. It’s toxic, messy and expensive. Really, the only reason it’s used at all by inexpensive resin 3D printers is because it is possible to obtain extremely high quality prints. You’re essentially trading operational pain for resolution.

If the quality of the FRF results were not as good, then why bother? The motion system of a cartesian 3D printer is unlikely to provide resolution better than a precision, fixed-mount LCD panel or SLA laser system. The requirement to wear protective eyewear alone is going to dramatically

Finally, it seems to me that this approach has so many ways to fail it could be challenging for most operators. The ability to make something work once doesn’t mean it will work thousands of times for others.

Regardless of the commercial viability, this is a very interesting experiment.

Via YouTube

Well, the concept is the same behind the Massivit machines, isn’t it?

Kinda, but the Massivit machine is, well, massively bigger, and uses a photopolymer gel instead of a liquid photopolymer as done in this experiment. Massivit also illuminates their entire (enclosed) build chamber with UV light, so they don’t need lasers. The gel holds up a lot longer than a liquid, thus allowing the lower powered UV lighting more time to activate the photopolymer.