Glass 3D printing is a very challenging technology but researchers have found a different way to 3D print that common material.

There’s movement towards sustainability by many 3D printing organizations, including use of recycled materials, green power consumption, bio-derived materials, etc. One very common material is glass, yet it isn’t 3D printed much at all.

The problem is that it requires extremely high temperatures to properly soften. And even then, “softened” glass is extremely viscous, making it near impossible to produce anything other than a very, very coarse extrusion.

Perhaps the only practical method of 3D printing glass I’ve seen so far is from Glassomer, a German company that invented a 3D printer resin that contains a huge proportion of very fine glass particles. A part 3D printed with their resin can be post processed into a near-pure glass object, even capable of optical applications.

However, Glassomer applications tend to be small glass objects. But what about larger methods of using glass in 3D printing?

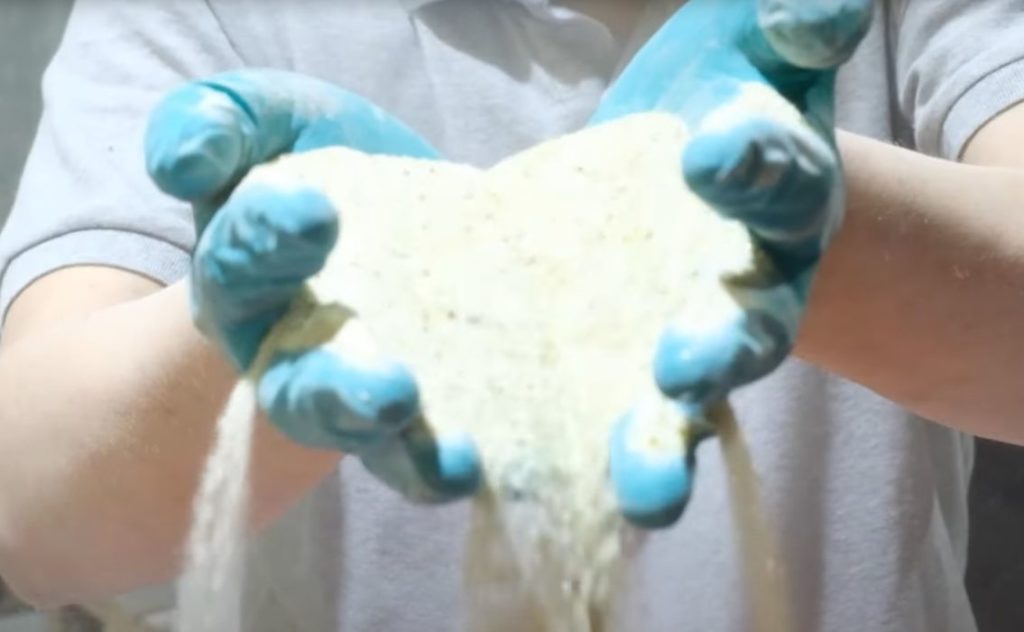

A new approach has been devised by researchers at NTU Singapore, where they sought to 3D print larger structures using glass. Their approach was actually quite straightforward: use standard construction 3D printing methods, but swap out the sand in the concrete mix for glass particles.

Standard concrete is a mix of cement and rock particles, or as we usually say, “sand”. The cement itself isn’t particularly strong, but when combined with sand it creates a very strong object when cured. The process is much like bricks and mortar: the bricks are hard, but the mortar is crumbly. But put the two together and you have a wall. Concrete is like that, except the bricks are tiny sand particles.

But what if you used glass particles instead of the traditional sand? The researchers tested glass particles of different diameters, ranging from “coarse” to “moondust”. While it’s possible to identify the mix that provides the best strength, here the researchers wanted to identify a combination that was optimal for 3D printing. This meant consideration of extrusion flow properties, as well as initial structural strength that would allow multiple layers to be built before curing. The researchers explained:

“The extrudability of the concrete is governed by the critical yield stress value, beyond which, the filament displays high levels of defects and discontinuities. The main challenge presented in the formulation of a printable concrete mix design is the contradictive requirements in the yield stress of the material. Nonetheless, a window of overlapping yield stress values allows the concrete to fulfil the extrudability and buildability requirements. Within this window, printable concrete can fulfil the extrudability requirements and yet possess sufficient yield stress for shape retention and buildability.”

Ultimately, the researchers were able to identify a practical mix that was used to 3D print the bench shown at top. This object was made with a combination of cement and glass powder.

The results are intriguing, and could eventually become part of future construction 3D printer systems, if the resulting material is stronger and or less expensive than current sand mixes.

This is possible because it turns out that while most regions have recycling programs, glass is often one of the lower use items from these programs. Finding a way to make practical use of “free” recycled glass could be of great interest for those seeking additional sustainability levels.

Via NTU Singapore and Science Direct