Charles Goulding Jr. considers where 3D printing sits in the future of furniture supply chain.

Lag Times

COVID-19 hit the furniture industry uniquely. On the one hand, home-dwelling spiked demand. On the other, manufacturing and supply chain problems made it impossible to meet that demand.

This dual-headed challenge led to lag times as long as four months.

Then, just as the pandemic’s end seemed near, a massive ship lodged itself in the Suez Canal. The chain of boats waiting for passage included many with furniture containers.

Ripe for Disruption

These supply shocks highlight an industry model ripe for disruption.

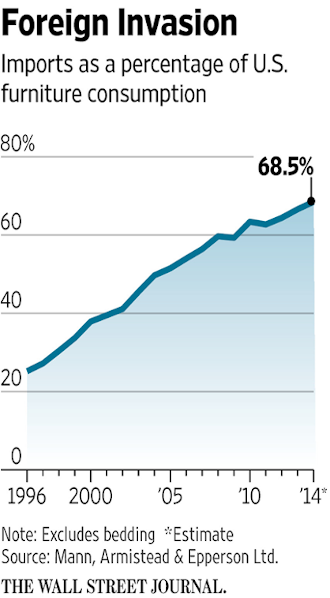

Thirty years ago, the United States produced the vast majority of its furniture. Between 1996 and 2014, however, imports tripled as a percentage of overall furniture consumption, from just over 20% to just under 70%.

Consequently, supply shocks involving exporters like China, Vietnam, and Mexico mean a great deal more today than they did in the early 1990s.

The US furniture industry’s long, complicated supply chains have other consequences, too: for one, a carbon footprint at total odds with global sustainability goals; for another, an emphasis on cost reduction and mass production at the expense of design creativity.

A New Model

Given these challenges, the time has never been better for 3D printed furniture pieces. They greatly reduce supply chains, drastically cut down on carbon footprints, and provide limitless design flexibility.

Model No. products go even further. The firm makes pieces on demand, eliminating not just supply chains but excess inventory.

The waste savings from this approach cannot be overstated. Furniture accounted for 12.2 million tons of waste in 2017, four-fifths of which ended up in landfills. By contrast, every piece Model No. makes goes to a customer.

Planting Down

Just as innovative are Model No.’s print materials. Instead of petroleum-based plastics, the firm uses biopolymers and plant-based resins. That means when you sit in a Model No. chair, you’re likely sitting on recycled food crop remains, like corn husks and sugar beets.

These materials help Model No. think about furniture end-of-life in novel ways.

“One of the reasons the company is called Model No. is that each product has its own individual number, and in theory you could send that product back to us, we can grind it down, and build you something new,” CEO Philip Raub told Fast Company.

Taking Off

Model No. is making headway. According to Bloomberg, the firm plans to establish 25 to 30 “microfactories” across the US and is in talks with a group of interested retailers.

Bloomberg featured the firm as part of its discussion of Biden’s infrastructure ambitions, including the desire to re-shore lost manufacturing capacity.

If Model No.’s plans come to fruition, that will be an example of a post-pandemic “new normal” in the furniture industry. Given the firm’s commitment to sustainability, speed, and customization, that would be a good thing.