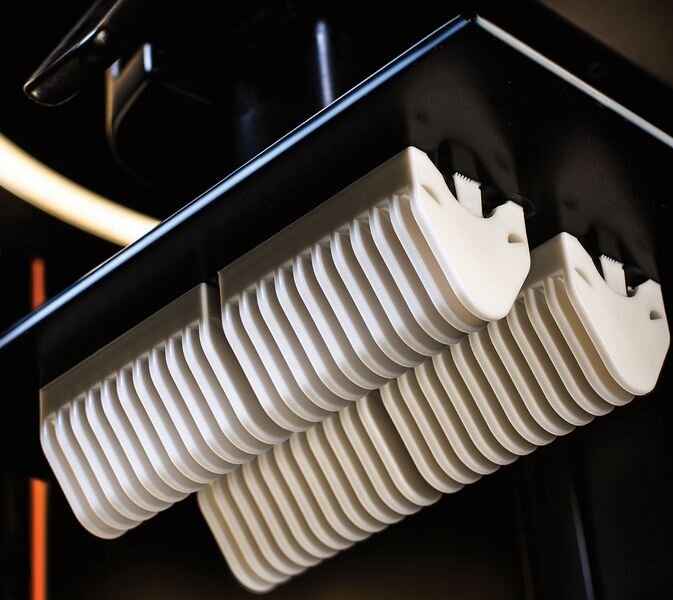

![Production 3D printing action at Xometry [Source: Xometry]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb08bacca94e.jpg)

I’m reading through a fascinating set of trends in 3D printing by Xometry’s Director of Application Engineering, Greg Paulsen and have some thoughts.

Xometry is a rapidly-growing fabrication service that launched in 2014 at their Maryland HQ. The company now has offices in Kentucky, California and Tennessee. They currently offer a wide variety of fabrication services, including:

-

CNC Machining

-

Sheet Metal Fabrication

-

Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS)

-

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

-

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

-

HP Multi Jet Fusion

-

PolyJet 3D

-

Die Casting

-

Metal Stamping

-

Extrusion

-

Urethane Casting

-

Injection Molding

Paulsen has written a relatively long set of trends that he sees unfolding in 3D printing. He says:

“3D printing (additive manufacturing) technologies have continued to evolve, adapt, and reinvent themselves. 3D printing has become commonplace with the added demand from engineers and consumers alike. The production of additive manufactured parts is commonplace at Xometry and nests nicely with piece-parts for prototyping or one-offs. With 2020 on the horizon, 3D printing bureaus must keep an eye on the future of 3D printing. Below are some of the hottest trends in 3D printing that will help elevate the manufacturing industry.”

Let’s review his four main points and I will add my own thoughts.

Paulsen’s Trend 1: Additive Process Control Software is On the Rise

Paulsen explains that there are increasing instances where 3D printing systems are using simulation to counteract possible failure modes encountered during 3D printing. One excellent example of this leverage is done by Velo3D, who employ sophisticated software to do so. We wrote in some detail on Velo 3D’s advanced 3D printing method last year.

I concur with Paulsen’s analysis here, and suggest that the phenomenon is also seeping into several professional desktop 3D printers as well. In particular, MakerBot’s new METHOD X employs a large number of sensors that are used to tweak printing operations on the fly to achieve better quality results.

There are also an increasing number of “closed loop” 3D printers that use servo motors rather than stepper motors to ensure absolutely correct positioning during printing operations. I now think that if servo motors were not so expensive they might appear a lot more frequently in the lower-end 3D printers. However, that may change in coming years.

Paulsen’s Trend 2: Increased Isotropic Print Possibilities

Paulsen notes the increasing interest in the phenomenon of isotropy, where materials are equally strong in all directions. Traditionally this has not been the case, as many 3D printing processes deposit material layer by layer, introducing zones of future delamination.

For many years the anisotropic properties of 3D prints was largely ignored by vendors, as it was a problem. However, new vendors such as Rize have figured out how to produce truly isotropic parts. And as Paulsen says, continuous SLA 3D printing approaches can also produce isotropic parts.

I think this could be a very important marketing feature in the near future for two reasons.

First, if a few vendors are able to produce isotropic parts, then they will use that feature to differentiate themselves from those who cannot. Thus there will be pressure on anisotropic providers to “get with the program”.

Secondly, the increasing interest in using 3D printing for end-product manufacturing will dramatically increase the requirement for isotropic parts. Vendors will have to meet this need by providing isotropic-capable equipment for the much larger manufacturing market.

Paulsen’s Trend 3: Novel Materials and Processes

Paulsen observes the increasing presence of very unusual materials beyond the usual thermoplastics and metals, such as ceramics, epoxies or silicones. I’ve also noted this increase, but there could be problems in execution.

These unusual materials face a dilemma in that being able to 3D print them means operators could produce many more geometries than previously possible, but they may not know what to make. The same problem occurred in plastic and metal 3D printing years before.

Now we see industries such as aerospace and automotive finally “get it” and there are now plenty of examples of 3D printed components that really do leverage the capabilities of 3D printing. But it took many years for those industries to learn about the technology and discover ways they could be leveraged for their respective applications. That has yet to be done with many of the new materials types.

Paulsen’s Trend 4: Viable Hybrid 3D Printing Technologies

Paulsen discusses the phenomenon where two or more fabrication technologies are linked together in a single piece of equipment. The best example of this is the several hybrid CNC-3D printing devices. In this type of device, coarse 3D prints are first printed, then they are milled down to precision surfaces with the CNC component.

Another example of this I’ve seen recently is AddiFab, who have managed to design a process that uses both 3D printing and injection molding. While the results of their process are actually injection molded, the geometric possibilities of 3D printing are inherited and open up many opportunities.

My thought is that we will see many more of these unusual combinations. Any equipment operator that is chaining together different fabrication systems to achieve a result is essentially identifying a possibility for a hybrid fabrication device, and one that probably doesn’t exist yet.

As manufacturers continue to seek efficiencies, there will be more opportunities to commercialize these unusual hybrid concepts. However, we’ll probably see a lot of experimental failures where a promising idea doesn’t catch on sufficiently to fund ongoing production.

I encourage you to read Paulsen’s full analysis.

Via Xometry