NASA has revealed their use of 3D printed parts on the Perseverance rover, currently en route to the planet Mars.

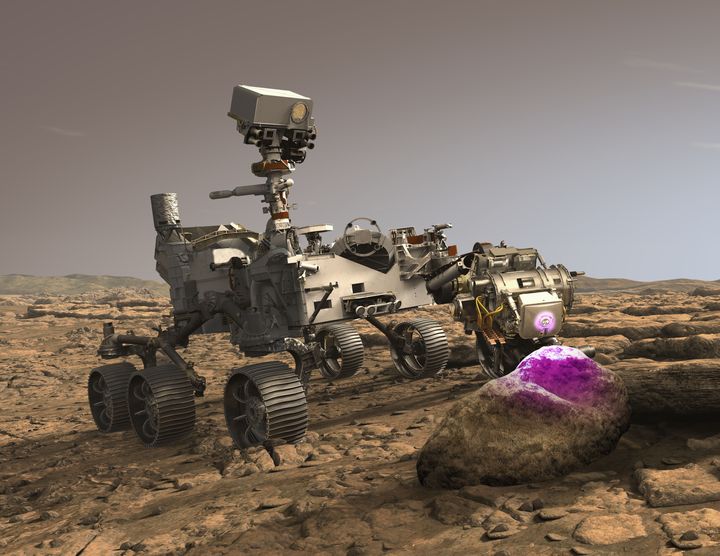

While it’s well-known that 3D printing technology has taken hold in the aerospace market, it’s quite interesting to see specific details of how it’s being used on a project. And there’s few projects as incredible as the Mars Perseverance Rover mission, which is set to land on the Red Planet’s Jezero crater on 18 February 2021, only a few months away.

You can even see the Rover’s current position in space with NASA’s Mars 2020 tracker.

This mission is a follow-up to the highly successful and ongoing Curiosity rover mission, and in fact the new rover uses many parts leftover from the construction of Curiosity. However, there are a number of different instruments — and some of them turn out to be 3D printed.

Perseverance 3D Printing

NASA says in a recent press release that eleven different parts of Perseverance were 3D printed. These were used in two major subsystems.

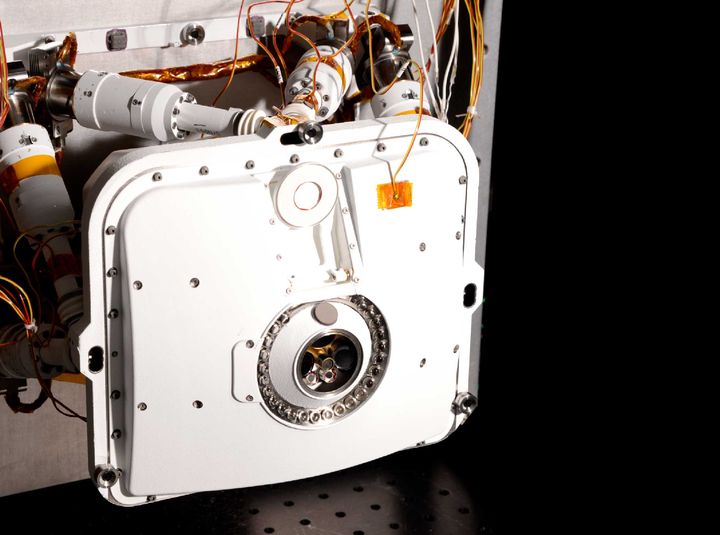

First, there were five included in the PIXL instrument. This is an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, a device used to identify the mineral composition of rocks on the Martian surface. PIXL is mounted on the end of the rover’s mobile arm so that it can be positioned adjacent to subjects of interest.

NASA explains what was 3D printed on PIXL:

“To make the instrument as light as possible, the JPL team designed PIXL’s two-piece titanium shell, a mounting frame, and two support struts that secure the shell to the end of the arm to be hollow and extremely thin. In fact, the parts, which were 3D printed by a vendor called Carpenter Additive, have three or four times less mass than if they’d been produced conventionally.”

Carpenter Additive is a Philadelphia-based full-service metal AM provider that can produce parts under a number industry certifications.

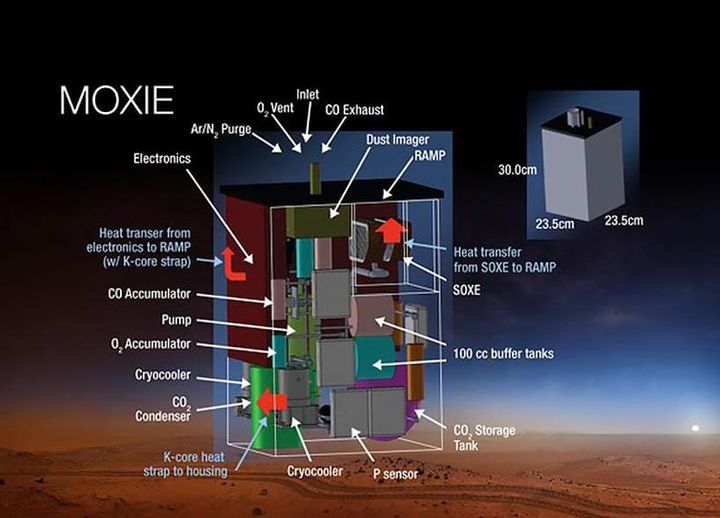

The other Perseverance subsystem using 3D printing is the MOXIE instrument. This is a device that is designed to produce oxygen directly from the Martian air. The device is testing a technique at a small scale, but one that, if successful, could be scaled up to produce industrial quantities of oxygen for planetary visitors from Earth.

The process involves heating up Martian air to a whopping 800C, which presumably breaks down the carbon dioxide to release oxygen. This extreme heat posed particular problems for the instrument, which must insulate it from the rest of the rover.

To do so, NASA engineers devised six 3D printable heat exchangers. These were designed to be 3D printed in a single piece, reducing the possibility of failure. A nickel superalloy was used to withstand the tremendous heat involved.

Ensuring Metal 3D Print Quality

There’s one elephant in the room here, however: part quality. It’s well-known that 3D printed metal parts often have two issues that can compromise their strength: porosity and microstructures.

Porosity is simply gaps in the part, which weaken it. On Mars the thermal experience may have additional effects on these gaps.

NASA used an interesting process to remove the gaps: exposure to a high heat isostatic press. Basically the metal 3D prints were placed in a high pressure chamber and heated to 1000C. This “pressed out” any gaps that existed. I have not heard of this process being used to “clean” 3D printed metal parts, but perhaps it should be investigated by others in industry producing critical metal parts.

The microstructure is the geometry of the crystallization that occurs when the metal material “freezes”, and if it’s not correct the part can be considerably weakened. To ensure this was correct, NASA engineers used microscopes to inspect the parts in detail.

The use of 3D printing on this mission has increased, as it seems NASA is getting more comfortable with the technology. This is quite notable, as that agency in particular must be incredibly careful in any technology steps forward. By using 3D printing in this way, they in effect set an example for other industries to follow.

Via NASA