A quirky 3D print experiment from a few years ago seems to be leading towards an amazing plastic IoT future.

“IoT” refers to the “Internet of Things”, a concept in which common objects become “smart” through the adoption of controllers, networks and software. Your smart fridge would be an IoT device, as would your smart doorbell, smart thermostat and other similar items. The thought is that the future will be awash in this type of object.

But there are many objects that cannot easily be “IoT’d” because it would be prohibitively expensive to equip them with radios, batteries and circuit boards. The IoT portion might exceed the cost of the item itself.

Thus there has been a kind of envelope into which everyone thought IoT devices would fit: items that already use electricity, have some reasonable size and employ mechanical mechanisms.

That concept might be headed for the trash heap if a new development from the University of Washington takes hold.

This work builds on previous research done in which scientists developed an unusual way for 3D printed objects to participate in WiFi networks. The idea was to 3D print specific shapes using conductive material. This material would reflect radio waves when transmitted near the object, allowing for rudimentary connections.

In 2018 they found a way to adapt this concept to enable remote monitoring of mechanical objects. The idea was to have the reflective shape distort its geometry during a mechanical operation, thus changing the nature of the electromagnetic reflection.

Now they’ve improved the technology even more. They have developed ways to generate electrical power using mechanical energy in the 3D printed object. For example, if a button was pushed or an appendage bent, the resulting electricity could be used to generate a signal.

Even more astounding, they have been able to transmit digital data by using a system of 3D printed gears that encode 1s and 0s. How does this work? It turns out that the gears reflect WiFi signals slightly differently depending on how they are configured.

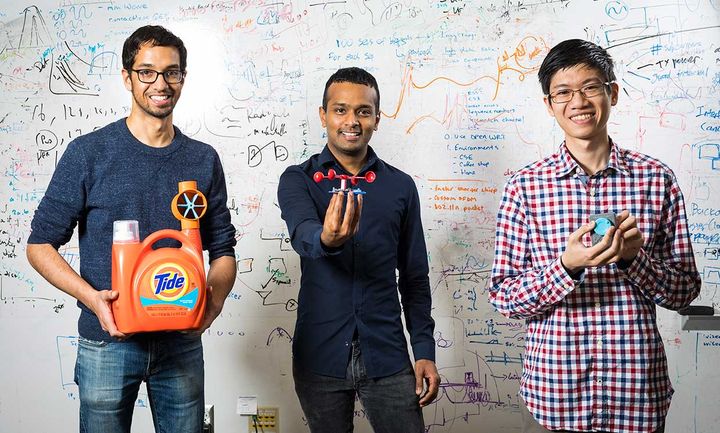

All of this has been done with normal 3D printers that in theory could be obtained by almost anyone. This opens up the possibility for an avalanche of new smart products that would otherwise be “dumb”.

The applications for this could include bottles that report when they are opened. This might be useful for pharmaceuticals, for example. General products could report on their usage without the need for any additional equipment.

In an extreme example, I could imagine something like a car dashboard being 3D printed in one piece that includes all the necessary switches embedded in the 3D model. The possibilities are endless here.

Via IEEE Spectrum