I’m reading an interesting story of how continuous carbon fiber 3D prints can be used to produce “self-sensing” construction parts.

The idea of self-sensing is powerful: imagine a building that could tell you, in real time, its current status. This would allow for much more detailed engineering analysis, which must periodically be done on most structures inhabited by people.

I’ve heard of the concept but never knew how this was accomplished technically. Then I read material from Moscow-based Anisoprint, who have apparently been able to produce such parts using their continuous carbon fiber 3D printer.

Continuous carbon fiber 3D printers are quite rare in the industry. Most carbon fiber you encounter is actually “chopped” carbon fiber that’s merely mixed in with a polymer. While that offers some added strength to the final part, the most strength can be obtained by inserting continuous, non-chopped, carbon fiber strands directly in a 3D print.

In early days that would have to be done manually after 3D printing: take two parts, lay some fiber in-between and join them together. Then a couple of 3D printer manufacturers figured out ways to perform this work automatically during 3D prints. The two most prominent 3D printer manufacturers doing this today would be Markforged and Anisoprint.

Self-Sensing Carbon Fiber

But how do you make a self-sensing part with continuous carbon fiber?

It turns out that carbon fiber, in addition to its amazing strength properties, is also electrically conductive. Even better, the electrical properties slightly change when the carbon fiber is bent, as would happen when the construction part is under stress.

Anisoprint explains:

“Self-sensing is the ability of a material to sense its own condition, the material itself is used as a sensor. Polymer-matrix composites, containing continuous carbon fiber, are known materials that have self-sensing capabilities based on measurable changes in electrical resistance of the continuous fibers. The practical importance of such products is in structural health monitoring in airplanes or critical parts of constructions like bridges. Usually, self-sensing material is made with the traditional composite manufacturing techniques that is the complex several-stages process made by the special equipment.”

Thus with appropriate electrical sensors on each end of the part and suitable software to monitor them, you have a self-sensing part.

![Chart of electrical resistance under stress of a continuous carbon fiber part [Source: Anisoprint]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0653f21780.jpg)

Chart of electrical resistance under stress of a continuous carbon fiber part [Source: Anisoprint]

One of Anisoprint’s customers, Dutch research center Brightlands Materials Center, has been experimenting with this approach to develop self-sensing 3D printed components.

The ability to precisely place the continuous carbon fiber strands within the part turns out to be critical to the self-sensing ability. While strand placement is usually done to enhance strength, there’s also reason to place them in locations most sensitive to stress for easy detection.

Self-Sensing Components During Design

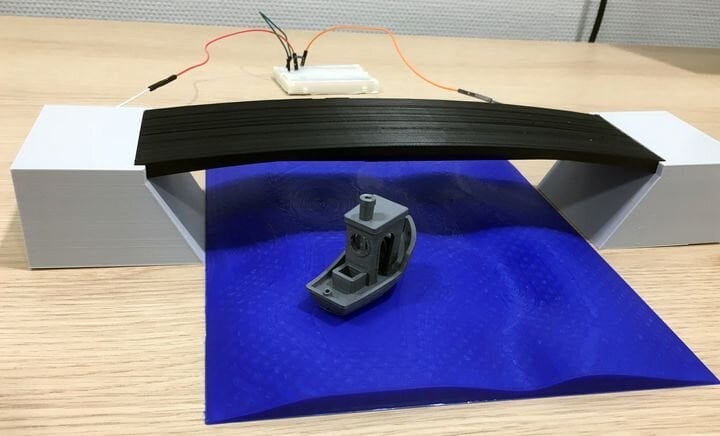

![Small-scale bridge 3D print to test self-sensing using continuous carbon fiber [Source: Anisoprint]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/anisoprint-self-sensing-testing_img_5eb0653f5ccd7.jpg)

Small-scale bridge 3D print to test self-sensing using continuous carbon fiber [Source: Anisoprint]

There are reasons to use this approach not only during final construction, but also during design of a structure. It’s possible to 3D print smaller versions of parts to allow experimentation during the design phase to better understand how loads would transfer. Anisoprint explains:

“3D printing sometimes requires several attempts and testing iterations to get the part with the required parameters. 3D printed self-sensing composites can help to gather information about the real use circumstances. That’s important for the design and prototype phase of new products or in replacing spare parts that are not available anymore.

During a testing period the self-sensing 3D printed part registers the real dynamics and forces that a product needs to withstand. This gives designers and engineers a clearer understanding of what requirements the 3D printed parts will have to meet. As a diagnosis tool 3D printed self-sensing orthosis or prosthesis might guide patients and provide valuable information to doctors, regarding stress distribution and movement patterns.”

This seems to be an entirely new usage pattern for 3D printing, and it seems considerably beneficial. I suspect Anisoprint and other 3D printer manufacturers producing continuous carbon fiber 3D printers will find many interested parties as this new approach unfolds.

In the future we may see many more “smart structures” relaying their status in real time.

Via Anisoprint

There are many applications where an embedded load or strain sensor has been used to provide what is called "structural health monitoring" or SHM of the component. Often these are special fiber optic filaments called FOBG (fiber optic Bragg gratings) that can contain hundreds of discrete stain sensors along the fiber length. Each of the sensors’ locations are known in the part and each can be individually interrogated, so that the strain field inside the part can be fully described. These FOBG filaments can be molded into a composite part, a plastic part or even a metal part (with Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing or UAM). In fact, you reported on this in your 17 Oct 2019 post "Fabrisonic’s Smart Metal 3D Print Build Plate".

Point is, while embedded sensors are not frequently seen in AM, they have been done before. And the FOBG technology has quite a few advantages (as a sensor) vs. the carbon fiber sensor approach described here. Not saying the CF sensor is not newsworthy, it is. But for folks interested ion embedded sensors, there are also more established methods that offer some advantages from a sensor perspective.