![UV resistant biopolymer concept [Source: ACS]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/biopolymer-research_img_5eb05087395de.jpg)

UV resistance is an important property for many 3D print applications.

This property is required for any parts that are subjected to outdoor use, where the UV wavelengths in normal sunlight can degrade UV sensitive materials. A degraded part could be a significant liability depending on the application, as it may fail at a critical moment.

The most popular 3D printing material today is PLA. PLA has outstanding 3D print capability, but is less useful due to two specific engineering property limitations. First, it has a rather low heat resistance. At a temperature of around 60C, PLA will begin to soften, and that’s a temperature that can easily be encountered on a car dashboard in summer.

Secondly, PLA is not UV resistant. Over time when exposed to UV light, typically outdoors, the material will gradually break down. That means that PLA 3D printed parts shouldn’t be used for outdoor applications. It is possible, however, to coat the PLA part with a surface covering that deflects UV radiation, but that’s extra steps.

To overcome these limitations many 3D printer operators turn to alternative materials. ABS is usually not appropriate, even though it has a higher heat resistance than PLA, because it is also UV sensitive. Instead, the go-to choice for outdoor 3D prints is usually ASA.

ASA is chemically very similar to ABS, and in fact its 3D printing properties are nearly identical. However, ASA adds the valuable UV resistance needed for outdoor exposure.

The choice of ASA is entirely suitable in many scenarios, but there’s one where it might not work. That’s when you require the use of biopolymer materials.

The need for biopolymer has been slowly increasing as a growing number of organizations seek to avoid the use of fossil materials. In some cases, it’s even required. However, for outdoor applications this has been a problem due to the lack of a UV-resistant biopolymer.

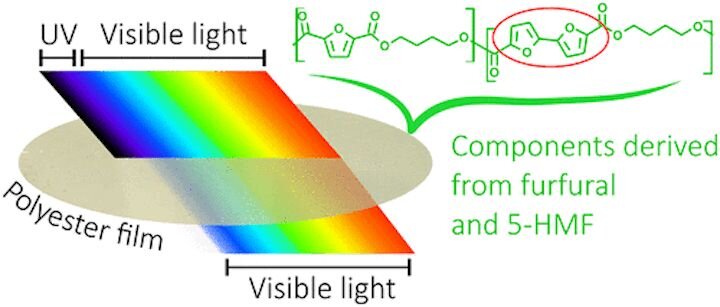

That may change as a result of some new research undertaken by a group of Scandinavian scientists. The paper, with the complex title of “Utilizing Furfural-based Bifuran Diester as Monomer and Comonomer for High-Performance Bioplastics: Properties of Poly(butylene furanoate), Poly(butylene bifuranoate), and their Copolyesters” demonstrates they have developed exactly such a material.

They say:

“Tensile moduli of approximately 2 GPa and tensile strengths up to 66 MPa were observed for amorphous film specimens prepared from the copolyesters. However, copolymerizing bifuran units into PBF allowed the glass transition temperature to be increased by increasing the amount of bifuran units. Besides enhancing the glass transition temperatures, the bifuran units also conferred the copolyesters with significant UV absorbance.

This combined with the highly amorphous nature of the copolyesters allowed them to be melt-pressed into highly transparent films with very low ultraviolet light transmission. It was also found that furan–bifuran copolyesters could be as effective, or better, oxygen barrier materials as neat PBF or PBBf, which themselves were found superior to common barrier polyesters such as PET.”

As of now, this is merely a research project, and this is by no means a commercial product. Even if it was, it would still have to be made into a proper 3D printing filament. In order to 3D print correctly, the material may have to be tuned with additives to ensure smooth flow, an appropriate temperature range, etc.

If and when that occurs, we’ll be able to use biopolymers for outdoor applications.

Via ACS