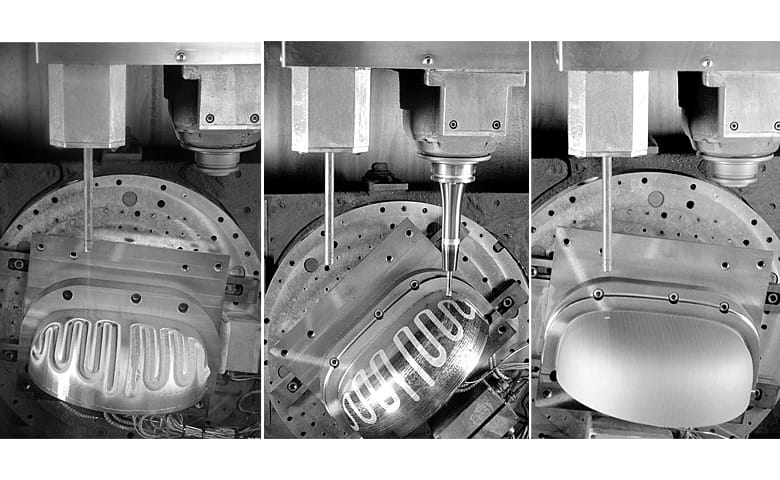

![A complex conformal cooling part produced with the MPA process [Source: Hermle]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb09fc1571ad.jpg)

We’re looking at yet another unusual 3D printing process, this time from Germany-based Hermle.

Their full company name is Hermle Maschinenbau GmbH; they are a subsidiary of the Maschinenfabrik Berthold Hermle AG near Munich dedicated to developing their 3D printing technology. They’ve been developing their technology for quite a few years, but have thus far been little known in the larger 3D print industry.

In fact they exhibited at formnext 2018 and somehow we missed seeing them, although this might not be surprising given that there were 626 vendors present. Fortunately, reader Benjamin Lakeit pointed us in their direction.

Their process is called “MPA”, standing for Metal Powder Application, and it seems similar to another company’s process we’ve recently seen. MPA involves blasting a fine metal powder at a target using a custom-designed nozzle. The load pressure exceeds 10Gpa and impact temperatures up to 1000C. The powder travels at a “very high speed”, which Hermle does not specify, although they do describe it as “super-sonic” as in this diagram:

![The MPA process [Source: Hermle]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb09fc1bee76.jpg)

The particles impacting the target have such energy that they naturally fuse into the material. By moving the nozzle around the target, layers of material can be quickly deposited. The company says they can deposit more than 200cc per hour, which is quite fast for any metal 3D printer of today.

The diameter of Hermle’s nozzle is “several millimeters”, thus making the achievable resolution on the printed object a bit coarse. There are two things to say about that.

![The nozzle used in the MPA deposition process [Source: Hermle]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb09fc238f81.jpg)

First, the notion of coarsely finished metal prints is not necessarily a bad thing: there are an enormous number of applications that don’t require fancy finishes. Foundries producing such products could easily find good uses for MPA technology.

Secondly, Hermle recognizes this deficiency and has corrected it by implanting the MPA technology inside one of their C-40 5-axis CNC milling machines. This combination allows for a smoothly finished object to be produced, yet also use a 3D printing process. Reading through their material it sounds like their system is quite flexible, and can, for example, mill the surface periodically during the print to ensure the CNC mill has access to the entire geometry.

One challenge with this approach is channels and cavities, as they might be accidentally filled with material due to the spraying nature of MPA. To counteract this Hermle apparently has a specialized support material that can temporarily fill such cavities. After printing this material can be “flushed out”. I’ve not seen this approach on other hybrid metal 3D printing systems.

Materials available for the MPA process include a selection of hot- and cold-working steels, stainless steel, invar, iron, copper and bronze. Some of these materials are not capable of being 3D printed by other common metal 3D printing processes.

From what we’ve read, it appears that Hermle’s process is quite viable and could be used for a variety of applications that are quite different from the most common uses of today’s metal 3D printing equipment.

It’s also quite clear that Hermle’s process is indeed very similar to SPEE3D’s, which we reviewed recently. It’s likely most of the implications we listed for the introduction of the SPEE3D process would be the same for Hermle’s MPA.

Via Hermle

FELIXprinters has released a new bioprinter, the FELIX BIOprinter, which is quite a change for the long-time 3D printer manufacturer.