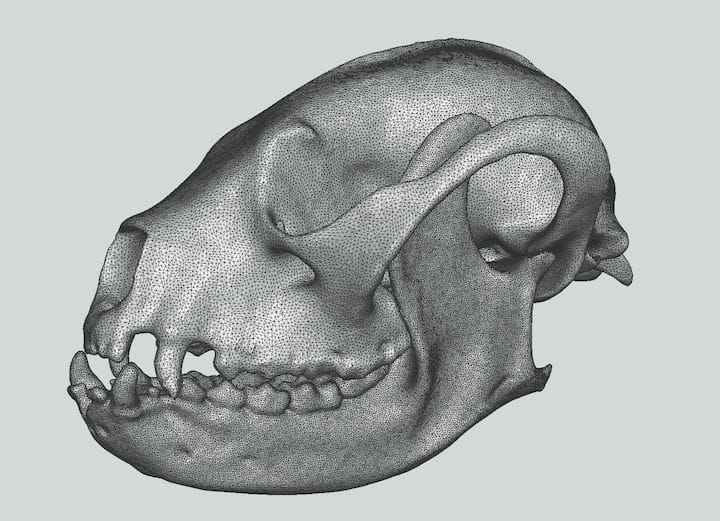

![A skull 3D model of Ailurus-fulgens, the Red Panda [Source: Fabbaloo]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a0f9015c3.jpg)

An enormous, decades-long project is launched to 3D scan virtually all fossils and specimens stored at major museums.

Details are very sketchy at this point, but it appears that both the US Smithsonian and UK’s Natural History Museum are among a series of notable institutions participating in the project to create a “Global Digital Museum”.

The goal of the project is to release the staggeringly large collections of the institutions to researchers, students, educators and others to the world at large, where much more research can easily take place by many more people.

The key reason for this is that traditional methods of deploying museum artifacts, public display at museums and backroom physical investigations, are entirely insufficient to handle the monstrously large collections controlled by institutions. The Smithsonian, for example, holds 40M specimens! Wait, UK’s Natural History Museum holds 80M specimens! Some of these are of incredible value and notoriety, such as Darwin’s specimens.

The scale of this project is astounding. The Smithsonian expects their work alone will take “50 years” to complete. To put that in perspective, by the time they finish, most of the people reading this story will be dead!

My first question was whether the 3D models would be merely displayed in proprietary 3D online viewers, as is often done to ensure the raw 3D models don’t leave the possession of the institution. This widespread practice has stunted the growth of research as you can’t do much with a 2D view other than look at it. If you were provided with a full 3D model, then all kinds of interesting engineering and biological studies could be performed, and, of course, the 3D model could be 3D printed.

They don’t say so explicitly in any material we’ve seen, but it appears to be the intention to deploy the downloadable 3D models to the public for all of this material, so that exactly that kind of research can be done. The BBC reports:

“Prof Emily Rayfield at the University of Bristol uses CT scans of dinosaur skulls and other bones to build computer models for research.

While it would be difficult even to lift the real, fragile, fossilised skull of diplodocus, for example, Prof Rayfield is able to twist, turn, compress and stress her digital dinosaur bones to reveal how the animals would have moved, what they ate and how they interacted with their environment.

This helped her and her colleagues to solve one the great puzzles about the sauropods – the small-headed, huge bodied dinosaurs in the same related group as the famous diplodocus.”

I spent some time poking around to see if I could find where one might actually download the 3D models. The Smithsonian doesn’t seem to have any word on that yet, but the UK Natural History Museum does has at least one partner, Phenome10K, that does offer downloads of the 3D models of interest to a specific project on marine mammals.

![Significant security failure in Phenome10K’s registration process [Source: Fabbaloo]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a0f95e977.jpg)

[CAUTION: While registration at Phenome10K is free to anyone, they carelessly send you a confirmation email WITH YOUR PASSWORD IN THE CLEAR. This is an extremely poor and dangerous practice that should not be done. Be careful when using this site.]

My hope is that the digitized 3D models, which can be as large as 2GB in size each, are stored in a single, massive digital repository that is easy to find and easy to use. That would be a rather challenging IT project, as it would require a massive database with all manner of scalability, storage, networking and financial issues to solve.

If so the work of researches and educators could be vastly simplified.

If only the rest of the world’s research materials could be provided to humanity in this way.

Via BBC, Natural History Museum and Phenome10K

It turns out there are indeed some 3D models in their archive, but it takes a bit of detective work to find them.