There’s a growing poop problem in 3D printing.

“Poop” is the casual name for waste material produced by today’s crop of single-nozzle multimaterial 3D printers. The single-nozzle approach drastically reduces the hardware price, and enables multimaterial 3D printing by repeatedly inserting and retracting different filaments into the single nozzle.

Single-nozzle approaches have been around for a while, most notably developed by Prusa Research with their MMU attachment. The MMU would pull filaments from the nozzle and then switch to a different filament.

The problem is that while the filament is swapped, there is still residual amounts of the prior material in the hot end. This must be purged in some manner. Prusa Research’s approach was to simply “print it out” in a purge block. This is a separate block printed alongside the actual print, and it accepts the mixed materials. After extruding on the purge block for a time the nozzle is declared “clean” with new material and then ready to go.

A related approach that’s proven popular is to instead cut the old filament and then purge the leftovers with an ejection instead of depositing it in a purge block. The ejected material is referred to as “poop”. This approach was pioneered by Bambu Lab, and has subsequently been adopted by a variety of other 3D printer manufacturers, including Anycubic, Creality, Phrozen, and others.

Both approaches work, but both are incredibly wasteful of material. Depending on the geometry of the colors in a 3D model, it’s easily possible to waste more material in purges / poops than is in the model itself!

There is a way to eliminate the purge / poop entirely, and that’s by using a tool switcher. In these systems there is a dedicated toolhead for each material, so there’s no filament swapping and no purge / poop. However, those systems are significantly more expensive because of the dedicated hardware. There are also limitations to the number of materials that can be used in these systems. Bambu Lab’s approach, for example, can support up to sixteen materials. On the other hand, Prusa Research’s XL machine has only five toolheads.

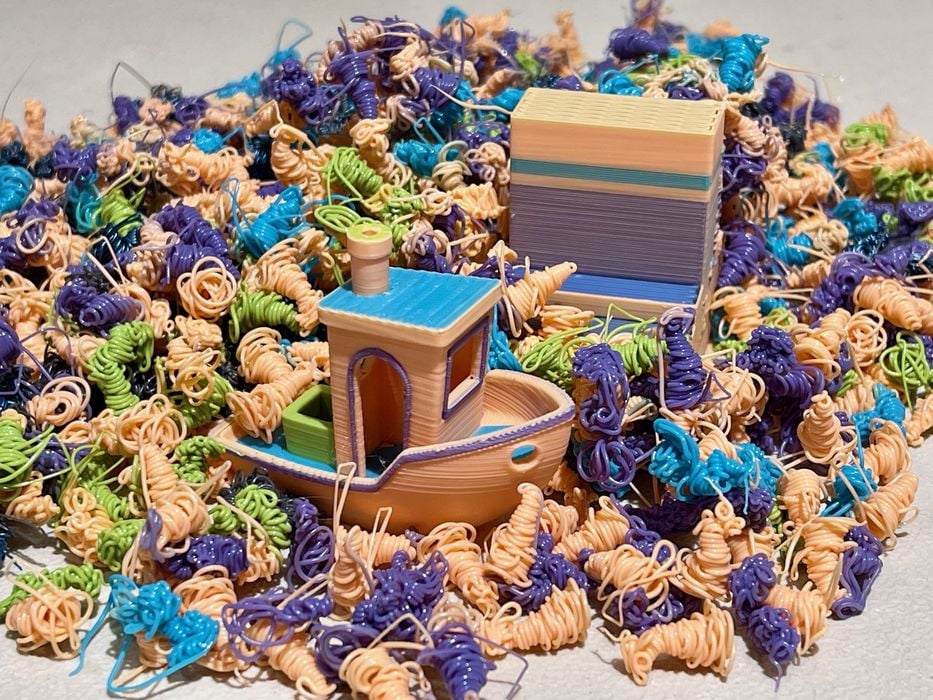

Here’s a recent example of a print I made. It’s a slightly colored #3DBenchy, which used four different materials. As you can see, the pile of poop is vastly greater than the boat itself. And a purge block was used as well! Even worse, the print took almost seven hours to complete.

This is quite wasteful, and the 3D printer manufacturers know it. Some have taken steps to reduce the amount of poop. For example, Bambu Lab issued a change whereby the filament would be strongly retracted to shrink the length of filament being cut off. This reduced the amount of poop considerably, but it’s still substantial.

While 3D printer operators tweak settings to reduce poop and purges, there’s something else afoot: media attention.

I’ve started to see stories published outside the 3D print space pointing out the massive waste of plastic taking place with these machines. While poop and purge blocks approaches tend to waste about the same amount of material, the poop is far more visible and appears larger to the eye.

That’s definitely not good in a world that’s concerned with microplastic waste. My poop pile shown above is the plastic equivalent of hundreds of plastic straws, for example. This amount of waste — and more — happens daily on hundreds of thousands of multimaterial 3D printers.

It hasn’t happened yet, but with a few more of these stories in the mainstream media we may see a rapid backlash against desktop 3D printers. It might take only a notable influencer to post some images to trigger a landslide of negative opinion.

That would not be good for the industry.

I’m not suggesting that we should hide the problem, however. Instead I believe we should FIX the problem. There is simply too much waste produced by these multimaterial systems.

I see several ways to solve the problem.

One is to somehow recycle the waste material. I’ve seen methods of pressing poop into sheets of polymer that can be used for other purposes. Would any 3D printer manufacturer produce a simple device for doing this? I haven’t seen any yet, but it seems like a no-brainer for a 3D printer accessory product. It’s basically a modified heat press, which should not be expensive.

Another approach is to more finely tune the pooping process. We’ve seen that Bambu Lab has already done some tweaks, and I suspect much more can be accomplished. Perhaps it would be possible to reduce the amount of poop by 50% or more by advanced tuning.

Finally, there is a wild card: a completely different approach to multimaterial 3D printing. Of course I don’t know what that is, but there are no doubt ingenious people thinking about this issue and hopefully they will come up with a solution.