A new research paper proposes an unusual 3D printing process that uses a rod instead of a flat print plate.

Print plates are near-universal in 3D print technologies, mainly because objects are typically built layer by layer. Those layers begin on a flat surface, be it a plate, resin or powder, and progress into a full formed 3D object.

However, researchers have developed a new form of 3D printing they call “Polar-coordinate line-projection light-curing continuous 3D printing”. Why change something that already works? It’s because the layer-by-layer approach doesn’t really work well for high resolutioin tubular structures. They explain:

“It is challenging for complex and delicate radially multi-material model geometries without supporting structures, such as tissue vessels and tubular graft, among others. In this work, we tackle these challenges by developing a polar digital light processing technique which uses a rod as the printing platform.”

Sure, but how exactly would this work?

“The 3D model fabrication is accomplished through line projection. The rotation and translation of the rod are synchronized to project and illuminate the photosensitive material volume. By controlling the distance between the rod and the printing window, we achieved the printing of tubular structures with a minimum wall thickness as thin as 50 micrometers. By controlling the width of fine slits at the printing window, we achieved the printing of structures with a minimum feature size of 10 micrometers.”

They were able to produce objects with thicknesses of only 0.1mm at the centimeter size — and do so in only 100 seconds. That’s quite rapid, and indicates there’s something to this highly unusual approach.

Their technology, Polar-coordinate Line-projection Light-curing Production, or “PLLP”, involves projecting a light pattern from a DLP source onto a rotating mandrel (or axle). This is utterly different from layered methods, but provides for higher print speeds and also stronger parts. It’s particularly advantageous for radially-oriented structures, as you might guess.

While the motion system of a PLLP system is something one can visualize, there’s more complexity in the slicing system. Normal layer-based slicers simply don’t work, and the researchers had to develop a new algorithm called “Polar Line Slicing”, or “PLS”.

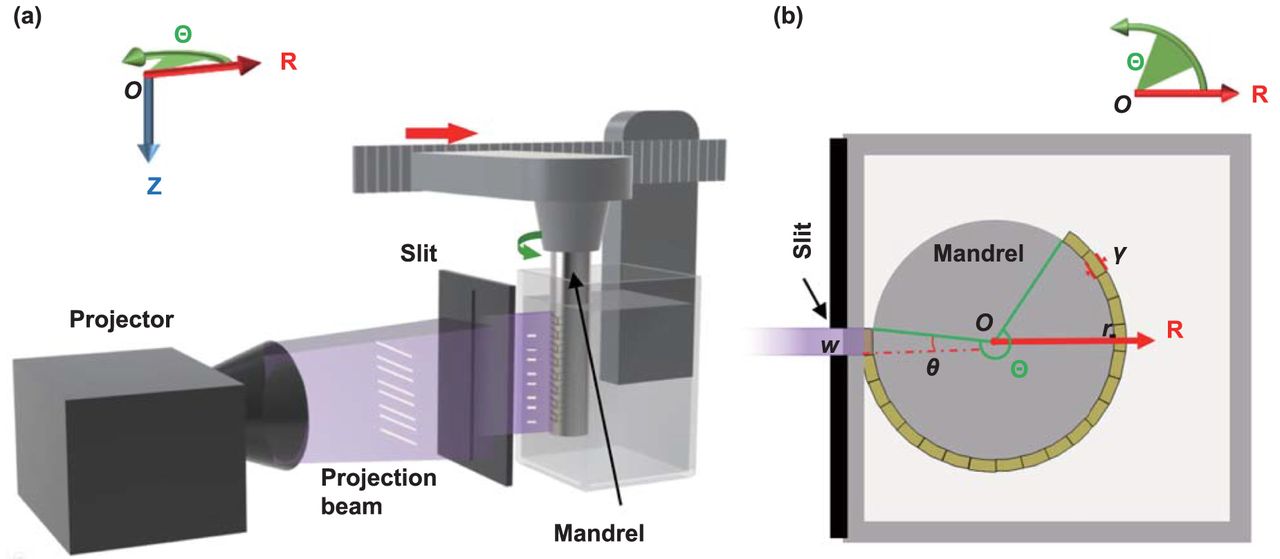

At top you can see how the hardware is arranged. The DLP projector is on the left, and it projects through a slit.

Normally DLP projectors illuminate a 2D array of pixels, but here only a single line of illumination is required because the mandrel is rotating in front of the slit.

On the right side of the image there’s a top-down view showing that the mandrel is positioned relatively close to the slit. This is because the photopolymer resin in the vat around the mandrel will cure as soon as the DLP’s light hits it. Therefore the “plate” has to be very close to the slit.

As material is solidified on the mandrel’s surface the mandrel’s distance from the slit slowly increases.

Note that the mandrel is rotating continuous, so printing occurs continuously, without the need for time-consuming layer changes. The solidified material doesn’t stick to the slit’s window because it’s rotating with the mandrel. However, this also means there are limitations on the layer thickness: thick layers require more light exposure, so the rotation would have to slow down. They explain their findings:

“Consequently, the achievable range for controlled curing time spans from 0.5 s to 1 s, corresponding to a layer thickness range of 50 μm to 100 μm (step size: 10 μm).”

If you hadn’t guessed yet, these factors make the slicing system even more complex: it has to handle the mandrel positioning and rotation as it changes throughout the job.

The researchers were also able to 3D print radial objects in multiple materials. They don’t exactly explain how this is accomplished, but it would seem that they simply pause the print and swap the resin vat with another containing a different material. Then the job resumes, but printing with an alternate material

Using this approach they were able to print a tubular structure that had an embedded layer of flexible material, for example.

This is a very unusual process that seems quite scalable. It may be possible to build larger-format 3D printers with PLLP that can print bigger parts in record time.

My only question is, how do you get the parts off the rod?

Via IOP Science