Researchers have developed a new 3D printing process that might eliminate the layer adhesion problem, and a lot more.

Layer adhesion is the bane of most 3D printing processes. Since the material is deposited layer by layer, the weakest point in the printed model will almost always be between layers. 3D prints are typically not isotropic, particularly when using the FFF process.

In FFF, molten polymer is extruded. However, it typically lands on the previous layer that’s already cooled, making it less favourable to bond. That’s why the layers break apart so easily.

The new approach was developed by researchers at Johns Hopkins and is called “voxel interface 3D printing”, or VI3DP.

VI3DP is actually quite straightforward, and I’m surprised it hasn’t been developed previously. This is how it works:

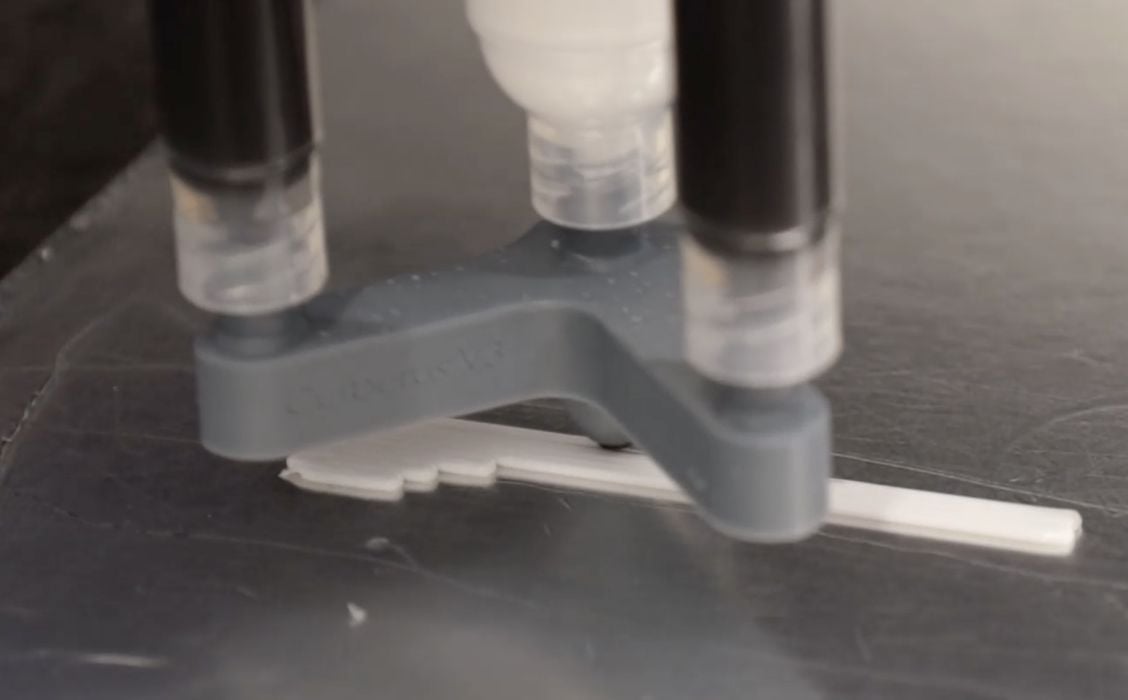

- A single FFF-style nozzle deposits material in the usual manner.

- The toolhead includes four more nozzles in a ring formation around the main nozzle.

- The additional nozzles squirt a film onto extruded surfaces as the print proceeds.

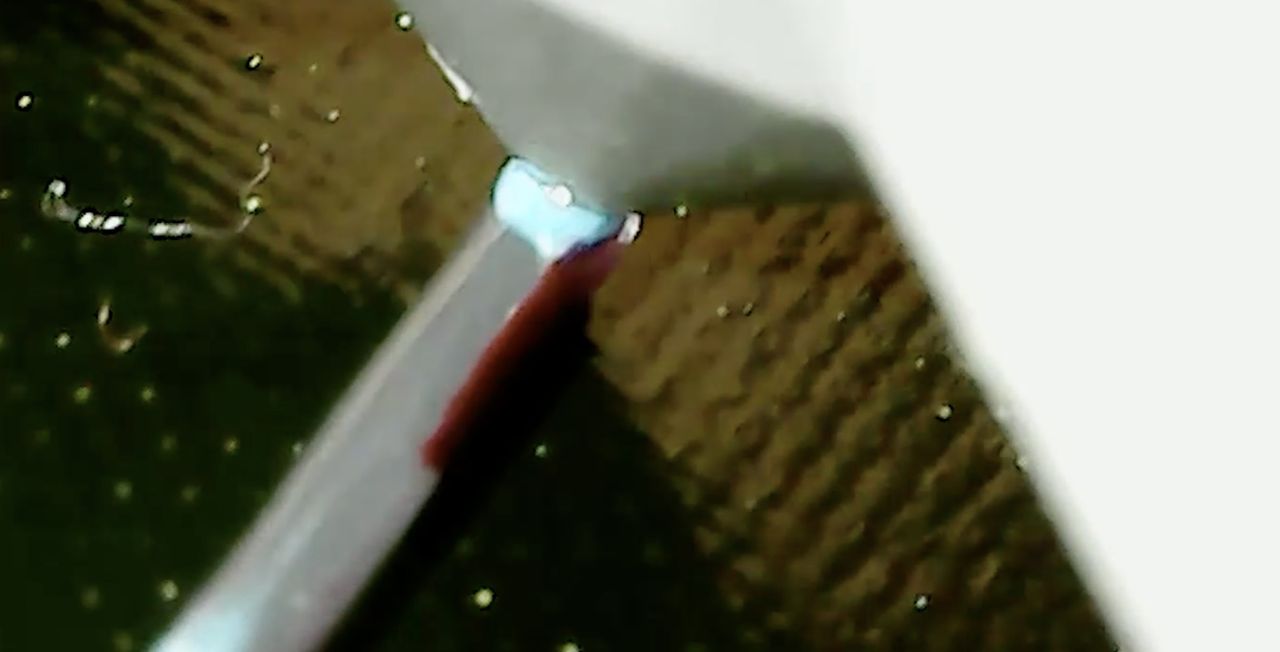

- The film can be used to customize the interface between layers.

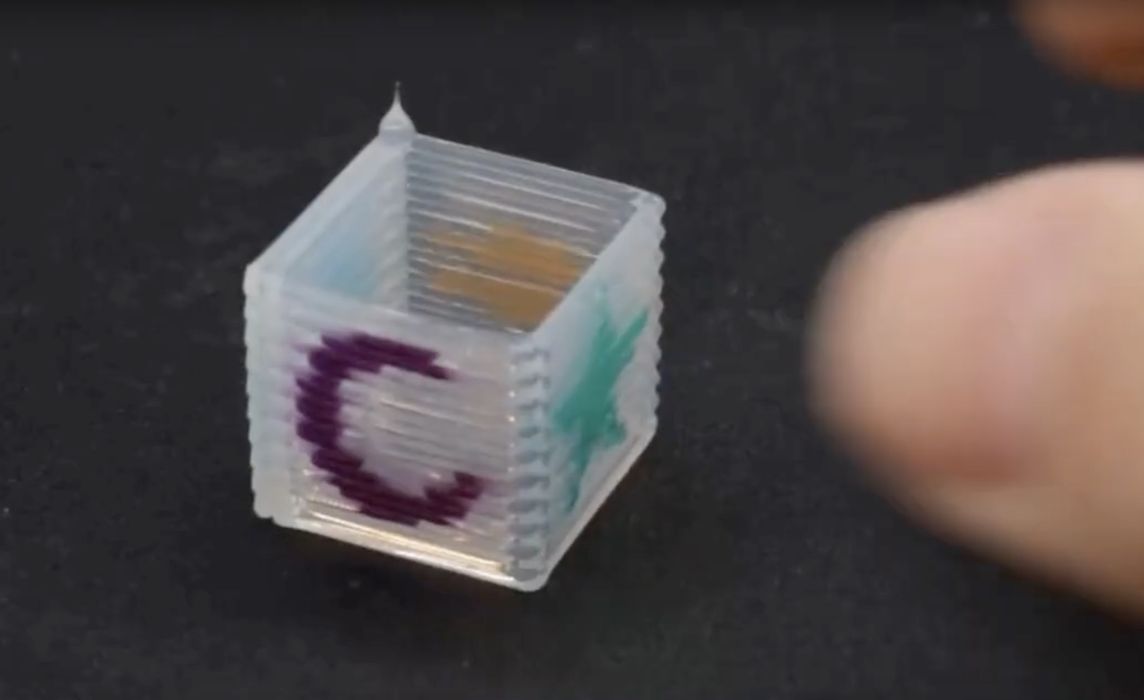

The customization could include materials to increase bonding or introduce other properties, like color, fluorescence, conductivity, or more. It’s possible to introduce several properties in a print job by loading each nozzle with different materials.

Assistant professor in Whiting School of Engineering’s Department of Civil and Systems Engineering, Jochen Mueller, explained the possibilities:

“Interfaces are extremely crucial because of what they can enable. VI3DP has the potential to produce thinner interfaces, new material combinations, and integrated functions like complex 3D circuits, electromechanical devices, data-embedded composite structures, and print-in-place mechanisms with precise fittings.”

It’s quite possible that VI3DP technology could enable printing of many types of objects that were previously beyond the constraints of traditional 3D printing processes.

The research team behind this work intends on continuing their investigation into the VI3DP concept, but I imagine at some point this may become commercialized.

If so, we’d likely end up with a professional-grade 3D printer with a number of very unique capabilities.

Via Johns Hopkins and Wiley