Two new research papers suggest there are possible ways to help solve the microplastic crisis.

3D printing produces a notable amount of plastic waste, with much of it ending up in landfills or the ocean. That’s because 3D printed parts rarely, if ever, have appropriate recycling labeling on them. Recycling centers then consider them waste instead of attempting recycling. Even if they did, the vast range of 3D print materials and colors makes it basically infeasible technically or financially.

That waste plastic eventually breaks down into microplastics, which blow and sail around the world. Microplastics are literally everywhere, carrying their random chemicals to where ever they land. Some are in the food chain, and even in your body, where their chemistry causes unknown long term damage.

Because of this increasing threat it’s important to consider the sustainability and recyclability of 3D print materials. Unfortunately there are really no good solutions as yet, and 3D printer operators continue to produce plastic waste. This is particularly apparent with iterative development, where many copies are made to achieve one final design.

Two new research developments may address this dilemma.

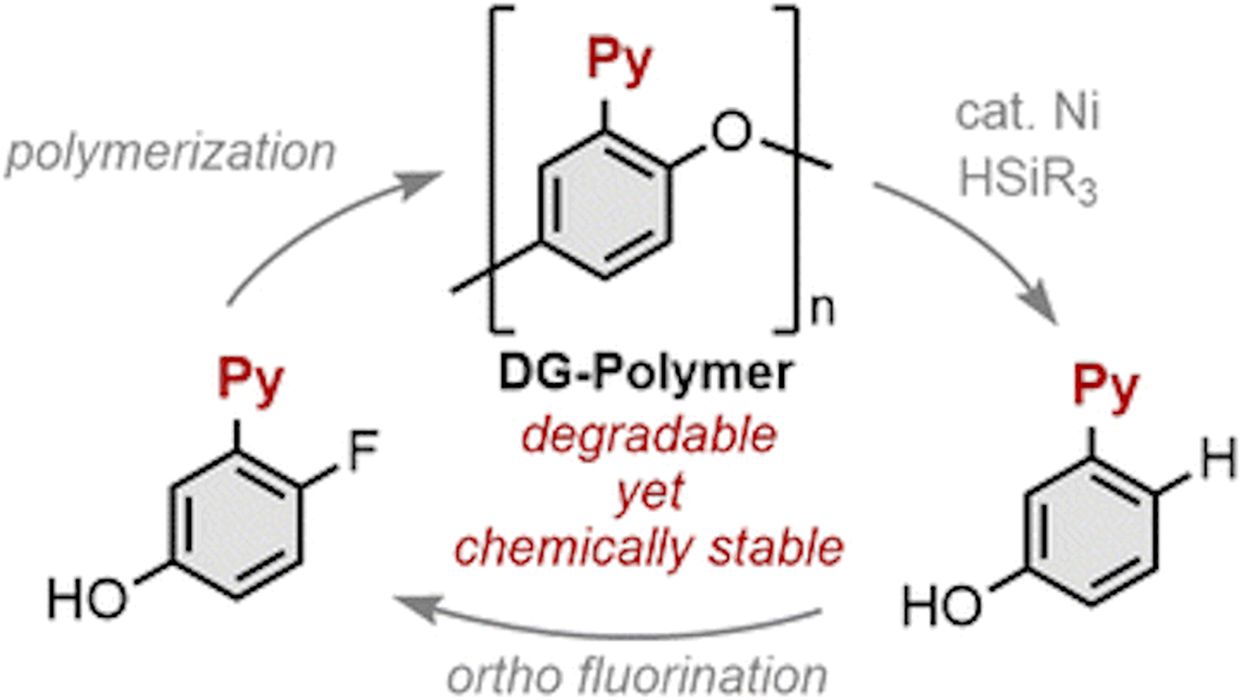

The first is from researchers in Osaka, Japan, where they have identified a method of fully recycling many polymers. They explain:

“To establish a sustainable society, the development of polymer materials capable of reverting into monomers on demand is crucial. Traditional methods rely on breaking labile bonds such as esters in the main chain, which limits applicability to polymers that consist of robust covalent bonds. We found that the integration of directing groups allowed the engineering of resilient polymers with built-in recyclability. Our study showcases phenylene ether-based polymers fortified with directing groups, which can be selectively disassembled under nickel catalysts via selective cleavage of carbon–oxygen bonds. Notably, these polymers exhibit exceptional chemical stability towards acids, bases, and oxidizing agents, while being degradable to well-defined, repolymerizable molecules in the presence of a catalyst. Our findings allow for the development of next-generation polymer materials that are chemically recyclable by design.”

What this means is that they’ve found a way to break down polymers into their component parts, which can then be used as raw material to produce new plastics. This effectively “resets” the cycle and starts over, rather than today’s method of recycling the same polymer over and over. During each iteration, the polymer degrades, whereas a newly formed polymer as the researchers suggest, would act as if it were brand new.

Their research suggests that it may be possible to devise new polymers with suitable strength and other properties that can take advantage of this approach.

If this were implemented, it might mean that polymer scrap could be properly recycled, even with differences in colors or material type. That would go a long way to reducing the amount of landfill and subsequent microplastics.

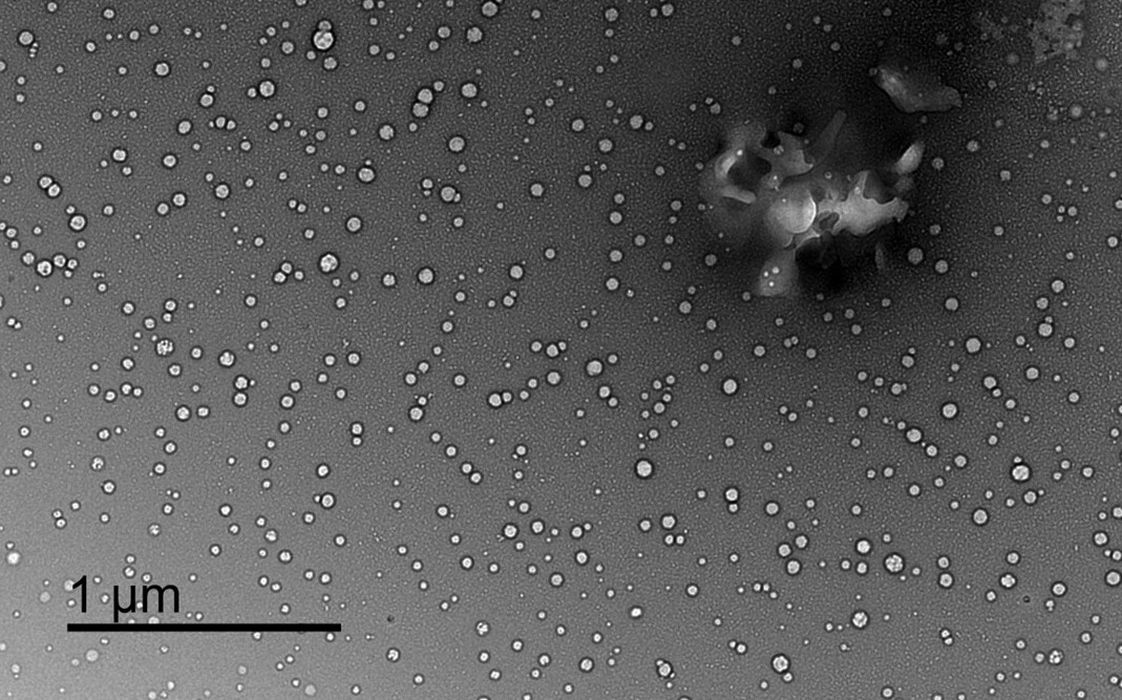

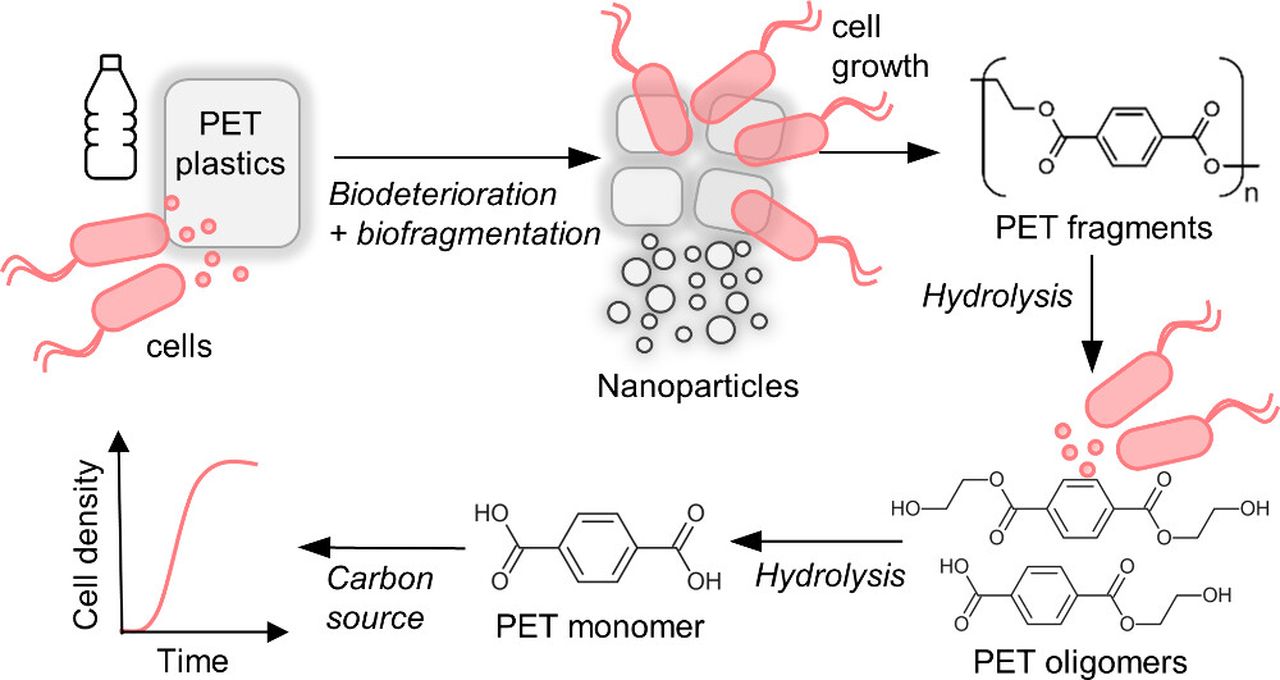

The second paper from Northwestern University and ORNL researchers discusses ways to remove microplastics already in the environment.

They’ve identified specific bacteria that can literally eat PET, a very common plastic used to make drink bottles. PET and its variant PETG are popular 3D print materials.

One way to implement this method would be to fit it into current wastewater processing facilities. One can imagine large tanks where the bacteria could remove PET materials before the water is released into the environment.

Microplastics are an increasing threat to society, and one where 3D print activity ultimately adds to the issue. However, research seems to be finding ways to reduce the problem.

That is, if we implement them.