Another milestone in 3D printing has been achieved: 3D printing a rocket engine from aluminum.

Rocket engines have been 3D printed for a while now, and it’s revolutionized the industry. Rocket engines typically have highly complex designs due to cooling requirements: if they aren’t cooled, then they will be melted by the high-temperature combustion exhaust.

The cooling is usually implemented by including tiny channels in the heat-exposed regions that can carry ultra-cold fuels on their way to the combustion chamber. This requires a highly complex design to include all the necessary channels. Making these devices is now vastly simpler due to the capabilities of 3D printing.

However, making a rocket engine in aluminum is quite another thing. Aluminum is among the lightest metals, so that would be quite desirable for a rocket engine. However, aluminum also has a relatively low melting point, and it can even ignite if temperatures are sufficient. How could you even think of making a rocket engine in aluminum?

That was the task set before LEAP 71, a company that produces 3D design software that uses computational engineering to generate complex 3D models. They’ve designed several rocket engines previously — even some that have successfully been fired — but not one made from aluminum. The proposed rocket engine would be 40X more powerful than their previous designs.

The answer was to make the design somehow even more complex. LEAP 71’s Lyn Kayser explains in a LinkedIn post:

“It uses a dual cooling strategy, with cryogenic liquid oxygen for regenerative cooling of the main combustion chamber, and kerosene for the upper part of the nozzle.”

It sounds like they doubled the complexity of the cooling system, but if that is what’s necessary, then that’s the design. The design attempts to keep the temperature of the aluminum below 300°C to avoid softening the material. LEAP 71 CEO Josephine Lissner explains:

”On an aluminum alloy engine, you want to keep the wall temperatures below 300°C, otherwise you are getting too close to softening and melting of the material. My understanding is that the auto-ignition temperature is more like 700°C. So before it explodes, the chamber will have disintegrated anyway, hence I don’t see it as the dominant failure mode. However, if you have loose powder left in the channels, that will very easily cause a reaction and trouble at lower temperatures already.”

The company used their PicoGK geometry kernel to rapidly generate the design, which was based on their previous work.

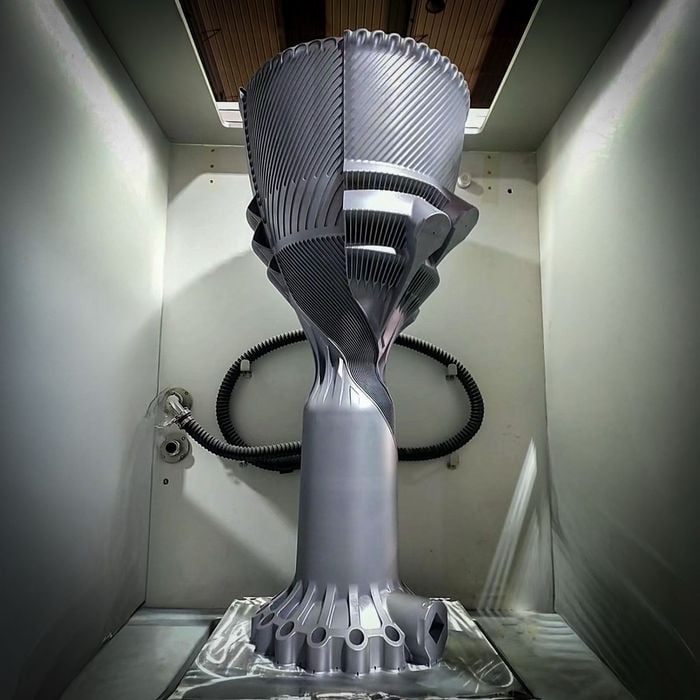

Once the design was completed, it had to be 3D printed. This was done by EPLUS3D at their Beijing facility over a period of 354 hours (that’s over two weeks!). The 43.5kg result you can see at the top.

It seems that even if 3D printing solves design issues with complexity, there is always another level of complexity that can solve even more.