Researchers have developed a new metal 3D printing process they call “RAD”.

RAD stands for ”Resonance-Assisted Deposition”, and it does not require any heat.

Let’s first look at how metal 3D printing is most commonly accomplished with today’s technology. That would mean heat. Lasers or electric arcs are used to quickly heat up material to the melting point, where it is deposited or accumulates according to the toolpath to build an entire 3D object.

These processes turn out to be incredibly inefficient. The heat used to light up the meltpool is inefficient because much of the heat is lost to the surrounding area, which also causes complications during printing.

Why heat? The heat increases the molecular diffusion through which new bonds form, joining molecules together. Heat is a measure of molecular motion, after all.

The researchers believed that diffusion could take place in a much more efficient manner. They developed a method of introducing pinpoint oscillations during deposition that would create optimal frequencies for diffusion to occur in specific metals.

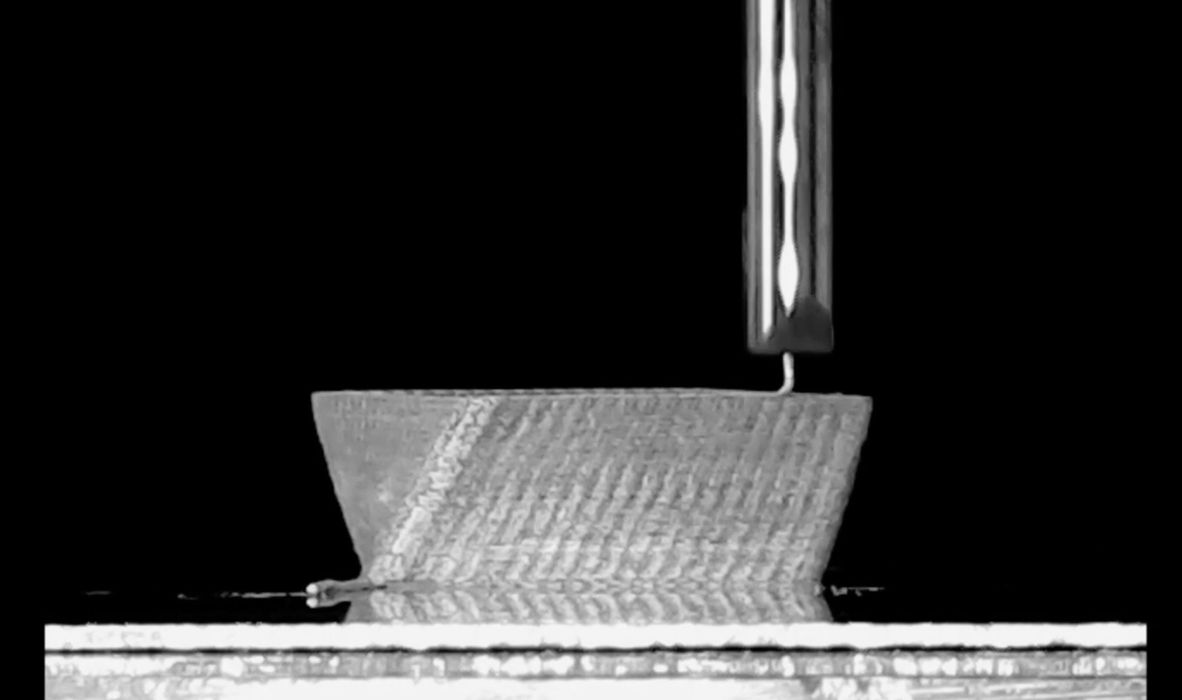

Their proof of concept involved a cartesian-style 3D printer equipped with a special print head. The print head involved feeding a standard metal welding wire through, where it encountered a transducer with piezo crystal oscillating at 40 kHz. This causes the extruded wire to join with previous material in the same way you’d expect a WAAM system to work, except that far less energy is required. They explain:

“Energetically speaking, using small-amplitude (less than a few tens of micrometers) repeated strains (tens of kHz) is roughly 30 times more efficient than using heat to cause the same amount of yield or flow stress reduction in metal shaping, under theoretical conditions with no heat lost or heat transfer from a 1 cm3 block of aluminum. In reality, the energy efficiency benefits are likely more than a factor of 30 because of the heat transfer and therefore losses during heating.”

Less energy means lower cost: no lasers, high energy electrical arcs or sintering are required. In fact, this approach seems so straightforward it would be easy to imagine an inexpensive desktop 3D printer that would operate with the RAD process.

Even more interesting is that RAD can handle unusual metals:

“It is shown that this method is significantly more energy-efficient than using heating, melting, and solidification. This method has the ability to print net-shape components from hard-to-weld alloys like Al6061 and the ability to print components with a high aspect ratio. Because of these specific advantages, this novel method has the potential to become the method of choice in applications where existing processes for metal 3D printing are lacking.”

If RAD is ever commercialized, it could revolutionize metal 3D printing by dramatically lowering the cost of operations. It could also enable large-scale 3D printing if one could assemble parallel RAD toolheads that could build larger objects.

RAD is simply research at this point, but it seems to me that it is almost certain that someone will commercialize this technology.

Via MDPI (Hat tip to Tuan)