I had a long discussion with Fred Pinczuk of Beyond Plastic about the potential for PHA material in 3D printing.

PHA is a unique class of polymers that has a property very different from any other: it is naturally biodegradable. In other words, you can freely toss it out into the world, and it will decompose on its own without any requirement for chemical or thermal processing. Because of this property, it cannot generate microplastic pollution.

Microplastic pollution is becoming a big deal, as we slowly discover that discarded plastics now pervade almost all environments on the planet, and even into our own bodies.

It would seem reasonable that some portion of 3D printing could shift away from the microplastic-generating PLA, PETG and ABS materials to PHA.

But this isn’t happening, at least not yet.

Beyond Plastic is a small company that hopes to make PHA “happen”. Pinczuk is the company’s Chief Technology Officer.

The company began with an exploration into a new material for making drink bottle caps, which are typically made from non-biodegradable polypropylene or similar materials. According to Pinczuk, bottle caps are the third most collected waste item int he USA. They identified PHA as a possible alternative material for this application.

They discovered that all of the (few) sources for PHA didn’t actually provide pure PHA: they provided PHA blends that combine normal polymers. The other polymers, of course, make the “PHA” non-biodegradable.

These were added to ensure the PHA blend had whatever properties were desired. But could pure PHA do the same? Pinczuk explained:

“On the plastic processing side of the things, it’s a really unique material because depending on the biomass which is used to make PHA, depending on the bacteria which is used to make PHA, you can actually get all kinds of different PHA’s.

I’m really simplifying here, but you can get from the very amorphous material, very soft rubbery material, to very highly crystallized, almost like a nylon type of material. So you really have a huge library of properties, mechanical properties and rheological properties. It’s almost like a category of material.”

Beyond Plastic adopted a marine biodegradability standard, which is apparently the highest standard one can achieve. Testing can take months or even years to complete, and Beyond Plastic has done this with some of their PHAs. It essentially means that the material can indefinitely co-exist with fragile marine organisms. Pinczuk explains:

“Why marine? It’s the most sensitive environment there is. It has the least concentration bacteria activity. It has wide range of temperatures from 27C degrees hot to 5C degrees average.

Microorganisms, which are in marine conditions, are very sensitive to toxins. So, if you have a polymer that has additives in there, or pigments, which are heavy. Heavy metals or whatever else, you can’t contaminate that environment.”

Why aren’t we using PHA all over the place? It’s because it’s a relatively unknown material, new to almost everyone.

“Its adoption into other fields has been very slow or very difficult for several reasons. One them being the fact that it has such a broad umbrella, category of material, to try to make work is very challenging when you’re trying to work with single-source materials.”

This seems to be the key to unlocking PHA: depending on how it’s produced, it can adopt a wide range of properties. If you try to use a PHA for application X, it may not work. But that doesn’t mean PHA is no good — it means you likely have the wrong type of PHA material for the job.

It turned out that the processing of the PHA was basically unknown, and Beyond Plastic set about to change this. They developed equipment to produce “five or six different formulations per day”, and they began a search for useful PHAs. Currently they have done over 190 variations, and have six “finished formulations”.

Pinczuk has noted that most of the PLA manufacturers have quietly removed marketing taglines like “biodegradable, plant-based, compostable, etc.” because they basically are not true. There are many demonstrations of PLA prints that just will not decompose, even after years of exposure.

Because of that flawed marketing, it seems that PHA may be by default dropped into the “fake green product” category by some. But it actually is a true green product, maybe the only one that’s ever appeared in the 3D print space.

Pinczuk believes in the future for PHA, but currently we’re at a “rough state”, analogous to the early days of PLA, when you’d often get a spool that was literally unprintable. There’s much development to be done, and a great deal of education on PHA.

Beyond Plastic has been working behind the scenes to persuade some 3D printer manufacturers to taken on PHA as a certified material, but so far they have not been successful. I was surprised to learn that one of the leading 3D printer manufacturers, one that issues regular sustainability reports, apparently dismissed the idea of pursuing PHA material.

There’s a very long way to go here, obviously. Beyond Plastic wants to trigger a shift to PHA material, but they don’t want to produce the PHA themselves at scale: their goal is to license the methods and process to others, much like what happens with other polymers today.

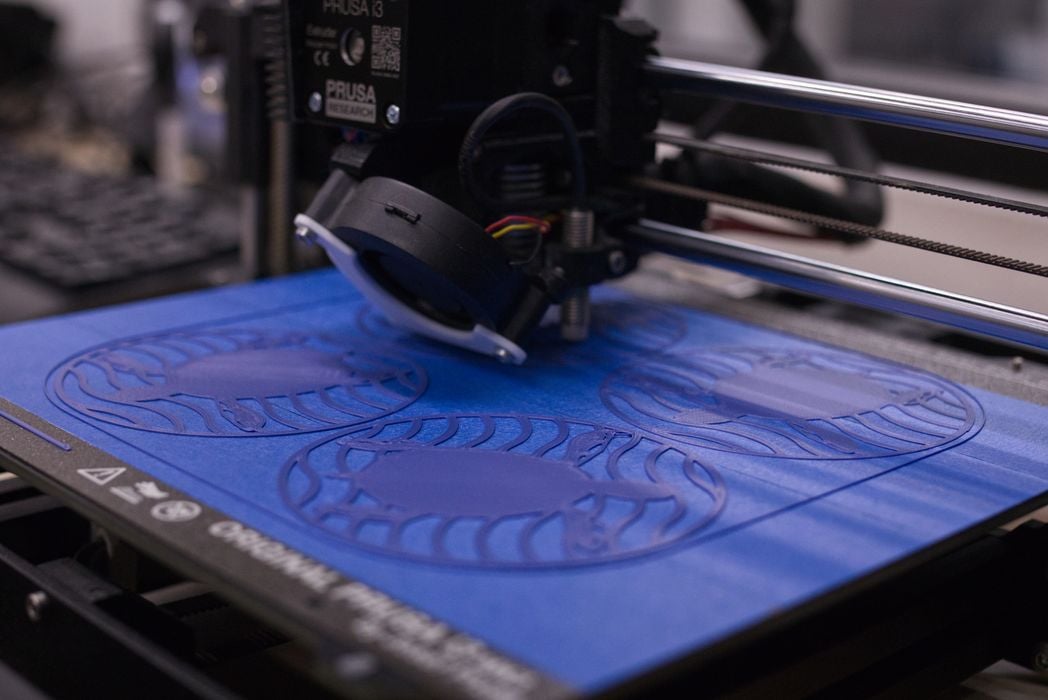

That said, the company has produced several types of PHA filament materials for purchase, including both rigid and flexible. We’re hoping to test some of these PHA materials soon, and we’ll find out how hard or difficult they might be to use, as well as the quality of the parts produced.

Via Beyond Plastic