Researchers have developed a new metal 3D printing process that vastly increases the strength of 3D printed parts.

While metal 3D printed parts may appear to be quite strong, they are not strong enough. This is particularly evident when undergoing repeated stress. This generates metal fatigue, which can cause the part to fail eventually.

That fatigue is due to a poor microstructure. If one were to take a microscopic view of a traditionally cast metal part, you’d see a consistent and tight microstructure.

Meanwhile, metal 3D printed parts, if inspected by that same microscope, would reveal voids and other tiny flaws. At the larger scale, these voids add up and weaken the part.

Manufacturers of existing metal 3D printers have spent considerable effort to minimize this effect through extensive parameter tuning. That would be adjustments to the speed of printing, temperatures involved and other factors. However, in spite of these efforts there really hasn’t been a significant breakthrough.

Now there is a breakthrough. The Chinese researchers developed a new process they call Net-Additive Manufacturing Process, or “NAMP”.

NAMP is similar to existing metal 3D print processes, in that parts are made from powder, layer by layer. However, there are extra things happening in-between those layers.

First, each layer is subjected to a hot isostatic press. This compacts the layer every so slightly, but sufficient to push the molecules closer together and squeeze out most of the voids.

Secondly, there is a brief heat treatment on each layer. This helps rearrange the metal’s microstructure to a more optimal form.

The results are quite startling.

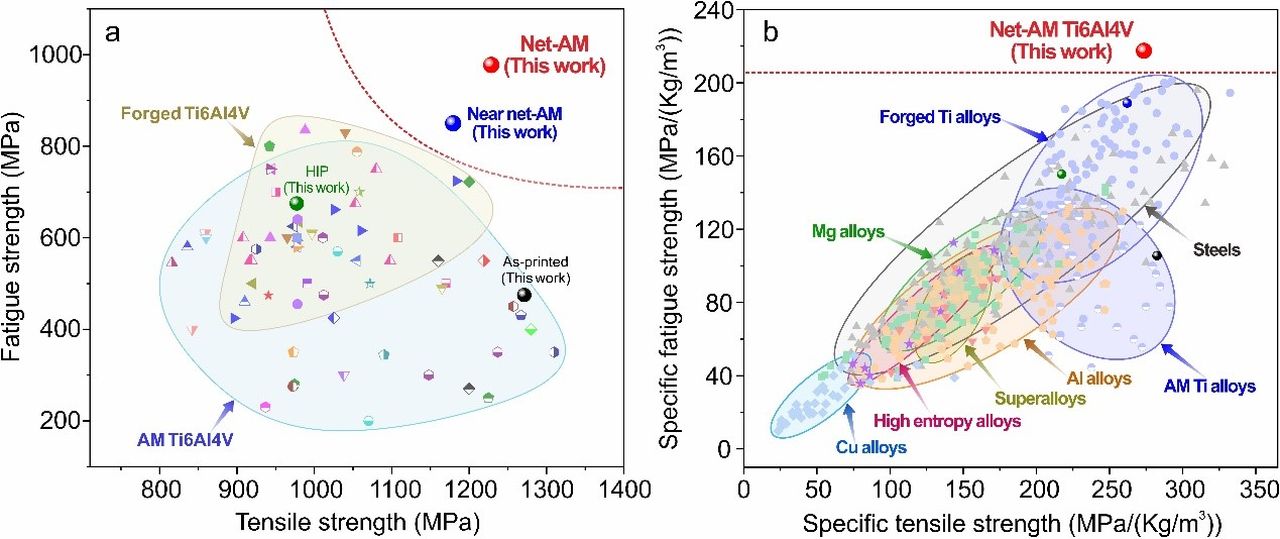

In the chart at top, you can see a plot of the tensile strength of metal parts. Both forged and additively manufactured parts are shown. If you look in the top right corner you’ll see the measurements for the NAMP prints as tested.

What’s particularly interesting is that the fatigue strength is quite significantly increased when printed with NAMP. That just might enable the use of NAMP-printed parts in more critical applications.

That would be good news for manufacturers of NAMP 3D printers, of which there are none at the moment. It would also be good news for operators seeking radically designed metal parts requiring extreme strength.

However, there could be an issue with NAMP. From the description of the process, it would appear that each layer would require considerably more time to complete. That would make NAMP one of the slower metal 3D printing processes.

On the other hand, it might be worth the wait if you’re able to make parts that can’t be made in any other way.

For now, NAMP is research. It seems that it should be worth a try to commercialize it, and that’s what’s likely going to happen in the next year or two.

Via Nature