This week’s selection is the Heart Aortic Valve by researchers at the University of Minnesota.

Medical 3D prints are becoming increasingly common, as they provide surgeons with significant benefits.

Normally a complex surgical procedure will require significant planning, as each patient’s scenario is unique. Surgeons will have to determine in advance the cuts, motions and paths they will take during the actual operation.

Traditionally this has been done using 2D tools like paper or images. But with the availability of 3D printing it is possible to 3D print full 3D models of the actual surgical area. These “hold in your hand” models can greatly assist the planning of the procedure because the surgeons can quickly examine the structures from all angles. It’s a more familiar method, too, as that is precisely what they see when performing the work.

The early medical models of this type were simple rigid, monocolor objects. They were helpful, but more could be done.

In the last couple of years Stratasys has been able to produce very high quality full color medical models with their full color 3D printing technology. While these have been very useful, there’s another step to be taken, and that’s to make the models physically act in the same way as real tissue.

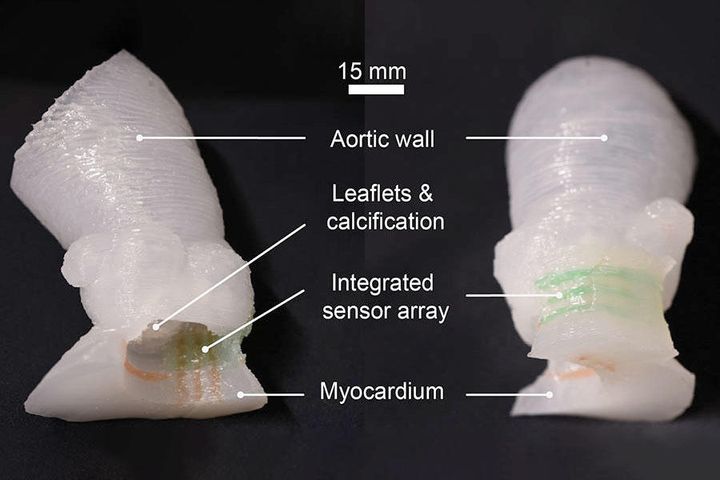

Researchers were able to achieve this by 3D printing a heart valve with flexible material that very closely matches the patient’s own tissue properties. University of Minnesota explains:

“The aortic root models are made by using CT scans of the patient to match the exact shape. They are then 3D printed using specialized silicone-based inks that mechanically match the feel of real heart tissue the researchers obtained from the University of Minnesota’s Visible Heart Laboratories. Commercial printers currently on the market can 3D print the shape, but use inks that are often too rigid to match the softness of real heart tissue.”

Here’s a video of the process:

It seems that these models are being used to plan the placement of devices within the heart. To aid the planning process, sensors were placed in the model to help surgeons understand the pressures being generated by the installation procedure.

This is a fantastic step forward that should greatly assist future surgeries.

Via Science Daily and University of Minnesota