Miguel de Unamuno, philosopher and writer of the Generation of ’98, and one of the most illustrious Spanish figures of the 20th century, puts in a certain essay:

“Invent, then, they and we will take advantage of their inventions. Well, I trust and hope that you will be convinced, as I am, that electric light shines here as well as there where it was invented.”

With these famous words Unamuno portrayed the Spanish way of life, which for centuries has denigrated science and technology, forgetting that the value of generating knowledge goes far beyond the simple enjoyment of scientific and technological advances.

In many countries, industry went from being the engine of progress to being relegated, year after year, to services. We have given priority to the low costs of manufactured objects on the other side of the world, but we have forgotten that having a strong industrial fabric provides valuable intangibles… It is not in vain that economies with a strong industrial component have been more resilient in the face of recent economic crises.

The tragedy of the COVID-19 pandemic has only reinforced this observation. In the face of the global shortage of basic necessities, such as personal protective equipment (PPE) for health professionals or respirators for the sick in hospitals, hundreds of thousands of anonymous people have fallen ill or died, faced with the impotence of States. Going to the market in search of masks, diagnostic tests or respirators has been frustrating. “Let them make it” has proven to be a failed strategy, unsustainable in the long run.

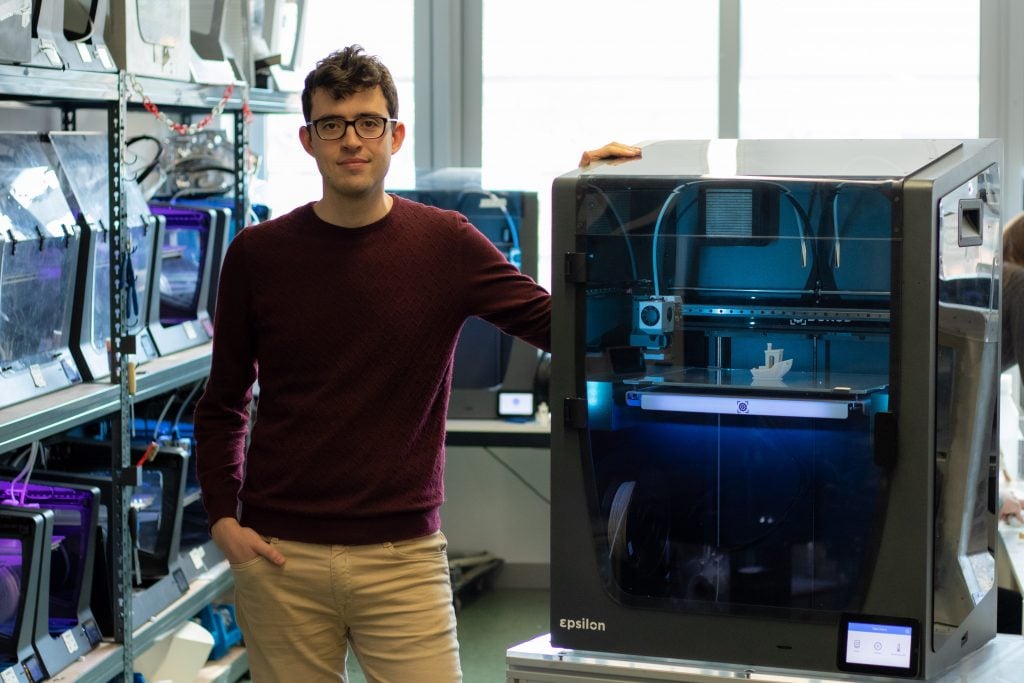

In the face of such a peak in demand, however, a technology has emerged, capable of providing quick and efficient responses, in a local and decentralized manner: 3D printing.

Unlike traditional manufacturing technologies that are usually based on subtraction or transformation of material, 3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, consists of the layer-by-layer contribution of the building material. As a result, 3D printing enables flexible manufacturing of objects, without the need to invest in moulds or tooling, without large initial investments or large industrial installations.

Although its production capacity cannot yet compete with traditional technologies, such as plastic injection, it allows the democratization of production capacity. There are 3D printing technologies, such as FFF (fused filament fabrication), which allow hospitals to manufacture dozens of pieces of PPE in just 24 hours with great quality. Or even private individuals can have their 3D printer on their desk at home and manufacture parts that, as we have seen in recent months, can save lives or preserve the health of our healthcare workers.

There is still great scope for improvement in 3D printing.

On a technological level we must continue to work to improve the productivity of the equipment, the compatible materials or the properties of the final part. Regulatory bodies must also adapt to this new industrial and technological reality. But there is no doubt that 3D printing, as a whole, has emerged strengthened from the health crisis caused by the COVID-19. And it will most likely be one more player in the battle for economic recovery. Industry must be strengthened, competitive and generate value; states must be able to supply themselves in the face of the expected upsurges; and companies must be agile, flexible and less dependent on the outside world.

3D printing technology will be reinforced after COVID-19 crisis. It is not a passing fad, but a key player in the coming industrial change.