Some months ago we wrote on the new 3D printing process by MELD Manufacturing.

We found out more about their new process with a visit and inspected the quality of their prints.

It’s a fascinating process that uses the principle of friction-stir welding. In this process, pressure and motion are used to create friction that melds – and not “welds”, as they insist – layers of metal together.

While their system can use metal welding wire as input material, they can also use metal powder, as many other 3D metal printing systems do. They say they can 3D print the metal powder “in open air”.

I am a bit suspicious about this, because while their process no doubt can actually perform in open air, this may be somewhat problematic. Some fine metal powder is actually toxic, so you should not be breathing it in, which could be facilitated by an open air setup. Similarly, some metal powders are also explosive, and this is why most 3D metal printers employing powder evacuate oxygen out of their build chambers before applying the lasers.

But MELD Manufacturing’s process doesn’t use lasers, so there is no heat involved. That said, I’d still avoid using powder until they develop a suitable and safe enclosure system for handling powder.

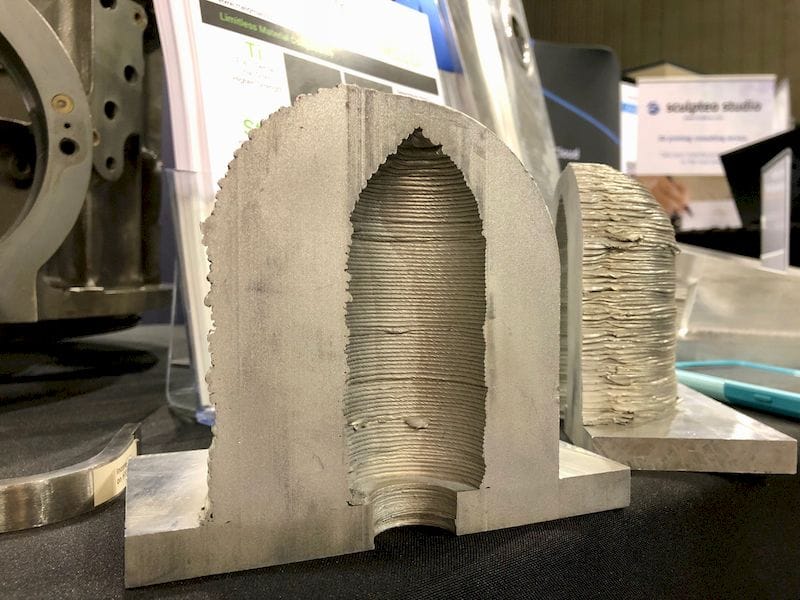

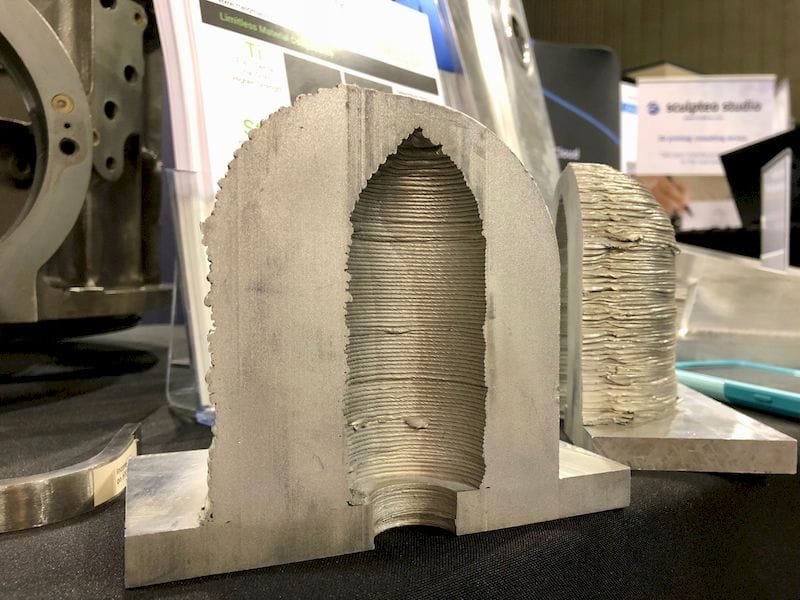

But using their system with wire should be entirely safe, and the results are quite good. Here we see an example print of a large metal part.

In the example, on the right side is how the part emerges from the friction-printing stage. It exhibits significant layering, as the MELD Manufacturing process does produce a rather coarse layering effect. However, the left side of the image shows the finished product, where they’ve CNC’d off the rough layering.

One interesting aspect about their process is that the molecular bonding is greater, and results in equal strength in all axes. This is quite different from other processes in which there delamination can occur on layer boundaries.

Another advantage of this process is that because there is very low heat involved in the layering, there is virtually no warping of the print, as is expected with other “hot” 3D metal printing processes.

The friction process also permits an ability to mix dis-similar metals, something you cannot easily do with most other 3D metal printing processes.

A disadvantage of the process is that it does not permit much overhang of structures, unlike many other 3D printing processes. This means that you will have some constraints on the possible object geometries you can print, but there are still many possible applications of this process, especially if you consider orienting the part in such a way as to avoid overhangs.

The company says that each machine is essentially custom made per order, so that the build chamber dimensions, for example, may vary. However, for reference, their B8 model, which comes with a very large build volume of 914 x 305 x 305mm, is priced at around USD$800,000. Additionally you would save costs over some other 3D metal printing options because the B8 would not require a particularly fancy operating environment.

If that’s a bit much for you, the company does offer a service in which you can get prints made with their own machines. I suppose this could be considered a “try before you buy” approach.

This adds to the ever-increasing choice of process for those interested in 3D metal printing.

1 comment

Comments are closed.