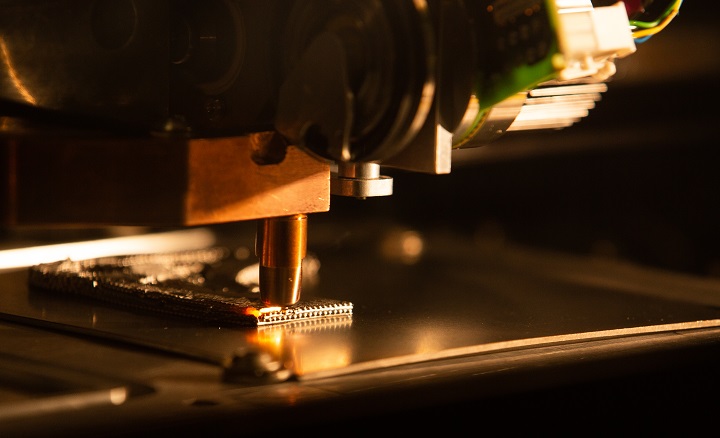

![Joule Printing in process [Image: Digital Alloys]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/process3B0A9376_img_5eb0a9194474c.jpg)

Digital Alloys recently announced $12.9 million in financing and two US patents for its Joule Printing metal additive manufacturing technology; I spoke with the CEO to learn more.

When Digital Alloys’ name first crossed the wire, it was in regards to a mysterious metal 3D printing technology that seemed to be doing well for itself with a $5 million Series A funding round before any details were released to the public. The company is a spin out of NVBOTS, as Dr. Paul Burke joined the team several years ago with the idea for what would become Joule Printing. Digital Alloys appeared Q1 last year as its own entity, focused on metal; today, the company employs about 20 and has plans to double, CEO Duncan McCallum told me.

For the last two decades, McCallum has been around venture-backed companies; in the last 12 years, he has worked as a founder and CEO, starting and selling two companies. In a fast-paced career of that sort, it takes something special to stand out from the crowd.

“When I saw Joule Printing, it was maybe the most amazing invention I’ve seen in my time with venture-backed companies,” he said. “It was something I couldn’t not do.”

‘Amazing’ can mean almost anything in 3D printing, so we dug into the what and the why behind Joule Printing.

“If you talk to companies about metal — and we’ve talked to over 200 companies now — it’s pretty clear why people are excited about 3D printing metal,” McCallum explained, starting at the beginning of the story. “Time is valuable, the ability to produce shapes and geometries you can’t with conventional is really valuable; the idea is to reduce overall production costs.”

With all the excitement surrounding metal additive manufacturing, one might expect for there to be more adoption than we’re seeing. McCallum noted that the first question talking to someone using the technology is what they’re using it for: “and the answer is usually nothing, or prototyping,” outside the “examples everyone talks about, jet engines and implants.”

Digital Alloys has identified three primary reasons for a lack of more use — three concerns that McCallum also says the company has solved with Joule Printing.

-

Machine speed is too slow.

-

Production cost, speed and material cost

-

Complexity. The machines are complex, and they don’t reliably produce high-quality parts without a lot of babysitting, hand-holding.

Joule Printing is based on the basic idea that a significant amount of cost in metal 3D printing comes from raw materials. The process uses wire, which is lower cost and lower waste than powder, in addition to being safer and easier to use in more production environments.

![[Image: Digital Alloys]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GIFPrint2_img_5eb0a91a88c36.gif)

Addressing the problem of speed, Joule Printing uses a precision wire feed system to “touch the wire to where we want to start a print and put current into the wire,” heating it from within, “like a coil in a toaster.” This removes the limitations of inconsistent material heat and because “you don’t have to wait for heat to move, there’s no speed limit.”

Addressing complexity, reliability, and consistency, McCallum pointed to the ability to constantly monitor real-time printing.

“It’s a closed-loop system; we’re always in contact and can measure directly how much heat is being generated because it’s a circuit. It’s measured in micro-second intervals, as a true voxel-level real-time control system,” he added. “We can use all that process data for non-destructive testing.”

Another advantage of the system lies in its capacity, by swapping wire at any point during any print, to mix metals together in any part for multi-material capabilities. The wire system additionally means a lack of a binder to remove or need for post-print sintering. The only post-processing necessary with this system is machining to create a smooth finished surface.

Digital Alloys is beginning, not by immediately selling machines, but as a provider of printed parts. The strategy, the CEO noted, is to be both a technology and service provider. They plan to provide services in addition to eventually selling the machines.

“If you want to do production in addition to prototyping, there’s a lot to put into place; it’s not just a fast, reliable, cost-effective printer,” McCallum explained of the approach. “What we’ve learned from talking to customers is it’ll go a lot faster if we do it all in one place. We have a factory in Burlington, Massachusetts. It’s small, and it will grow, and we’ll do it all there first. Boeing and other partners are helping us in how to build a factory around this marvelous Joule Printing technology. Once that’s done, we’ll make the printers available for sale.”

![[Image: Digital Alloys]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/DigitalAlloysPrinter_img_5eb0a91b3c177.png)

Another key aspect of the service provider approach is that Digital Alloys is “working only in applications where we can reduce production costs relative to conventional manufacturing,” which McCallum acknowledged as “a high bar.”

Competing with traditional technologies starts with a focus on reducing material costs, of which there are many in machining materials such as titanium and Inconel due to relatively large amounts of scrap generated. And, he said, “If you can deliver near-net shape at a low enough price point, you eliminate those costs.”

“If we’re not cheaper than conventional we’re not interested at the start,” McCallum said. “We want to deliver big wins to manufacturers, not cool examples of 3D printing.”

Two of Digital Alloys’ initial launch applications, generating more than a dozen orders for first parts, are conformally cooled tooling and cost-reduced titanium parts

In discussing applications, we also touched on where it is that Digital Alloys fits within the burgeoning metal additive manufacturing competitive landscape.

McCallum noted three primary categories of metal 3D printing: powder bed fusion, binder jetting, and directed energy deposition (DED). Noting competitors in each, as well as strengths and weaknesses, he said that the Digital Alloys team has found their sweet spot in applications creating parts “a little bigger than a baseball to a little smaller than a beach ball, for parts with full density,” where “we think we have a pretty clean running field ahead for us.”

Having discussed competitors, including several notables in Digital Alloys’ Boston-area stomping grounds, McCallum was very clear that that competition is a very good thing.

“We want all of these companies to be successful. It’s good for us, it’s good for the industry. Their success doesn’t have any impact on our success, just like CNC doesn’t compete directly with forging. It’s the right tool for the right part for the right application. We think metal 3D printing is the same,” he told me.

Finding these best fits involves, especially now at this nascent stage of metal additive manufacturing, honesty in offerings and approaches.

“We don’t think vendors are doing the industry a favor by claiming to do more than they do. We don’t think that’s necessary, we don’t think that’s helpful to customers, we don’t think that’s the right way for us to grow our business. If a customer comes to us with something better fit for another approach, we’re happy to steer them that way,” he said.

Digital Alloys is working with several customers, including series B investors Lincoln Electric and Boeing, as well as aluminum casting giant Nemak. Upcoming announcements over the next quarter will largely be focusing on customer news; “other things happening we won’t announce for a while.”

IMTS, which will be drawing quite a turnout among the metal additive manufacturing players, will see Digital Alloys among them. This is a technology I look forward to seeing in person next month in Chicago.

Via Digital Alloys

Aerosint and Aconity have proven out their work in multi-metal powder deposition 3D printing.