I’m reading a story on how 3D printing technology enabled a new kind of product testing.

To me the most important aspects of 3D print progress are those moment when someone discovers a way to leverage the technology in unprecedented ways, ways that provide a benefit unachievable with other technologies.

This seems to be one.

The project undertaken at Imperial College London intended to perform testing of a low-carbon engine. This required iterations of testing using different design attempts for multiple components of the engine.

Normally this would require manufacturing of the metal parts in an expensive and time consuming manner, making the elapsed time of the entire test set far too long.

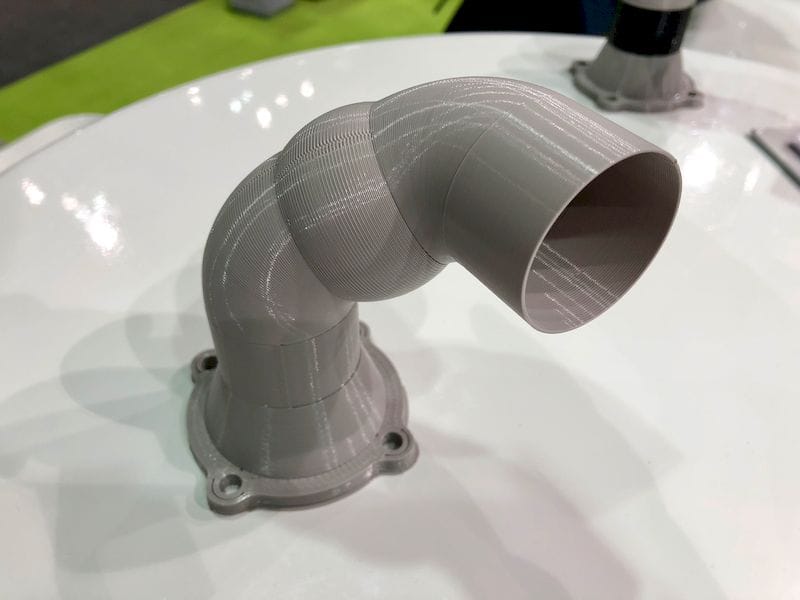

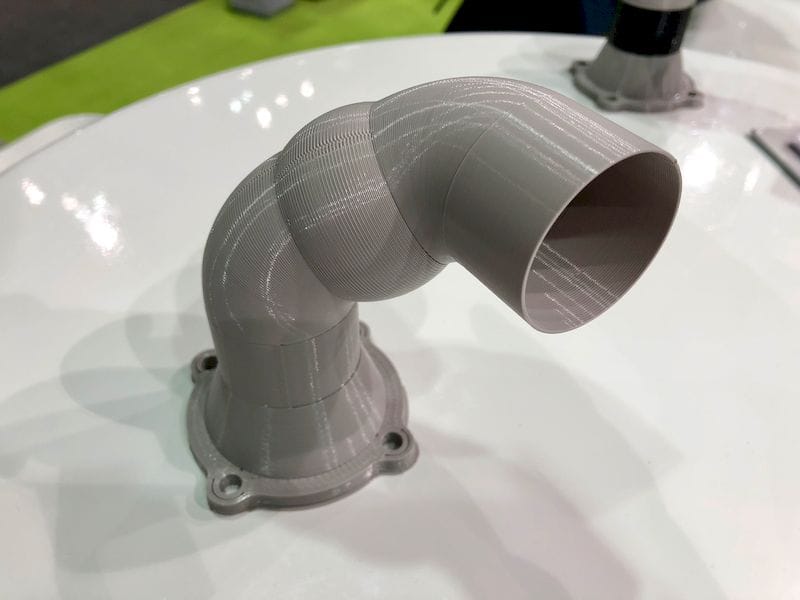

The researchers did something quite interesting. They redesigned the test rig to ensure some of the test parts were serviced with fresh, cool incoming air. This kept them at a temperature low enough that they could be 3D printed in thermoplastics instead of the usual expensive metal materials.

Thus they could far more rapidly perform the tests on the designs by near-instantly 3D printing them instead of waiting for metal equivalents.

But let’s make this clear what has happened here: They adapted an existing design to accommodate 3D printed components.

While they may identify the best part designs using this process with thermoplastic parts, the actual production parts would likely be made from metal. So this is merely an approach for testing – but it’s a very good one because it lowers the costs and greatly speeds up the effort to achieve the same results.

I’m now wondering if this technique could be applied in other situations where heat is involved. Could it be possible to apply external cooling on thermoplastic components during test situations to simulate metal components? Could this be a routine technique for future metal part development?